Thursday, July 31, 2008

Mike T Nelson: sharing the Protein and Carb and Pain Relief Joy

Mike T. Nelson. RKC, King of Mn. Z Health. PhD candidate (profile/interview here)

Plainly Mike Mike has learned a great lesson of academics: reuse. Michael's been doing the skull cruching work of doing the exam papers for his PhD to show he's an expert in his field, before going deep with his big D, dissertation, to show he's an expert in his area.

Now our happiness out of this is that while digesting all the latest and greatest info in his area, he's been feeding it back out on his blog so that you don't have to.

His latest synthesis, found in his MyNotes at the end of presenting a paper's abstract, is on his blog RIGHT NOW. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Monday, July 28, 2008

Alwyn Cosgrove on the Anti Crunch

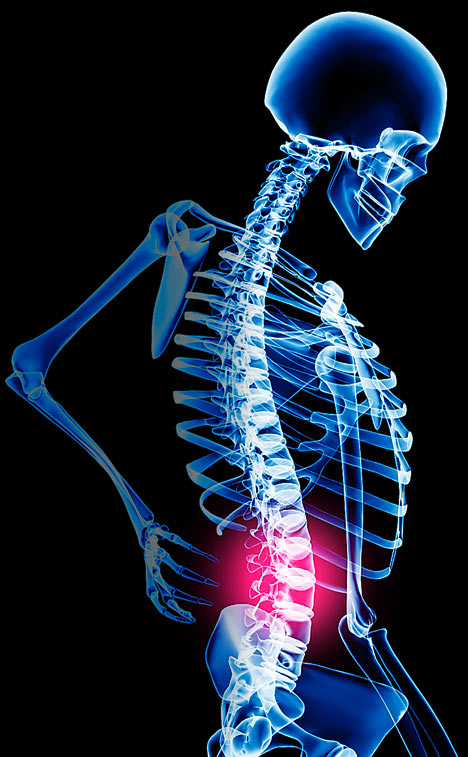

Worth checking out is Alwyn Cosgrove's post about awesome ab routines that kill the crunch. And would likely pass with the Stuart McGill seal of approval for low back performance.

If you've not heard of Stuart McGill and care about things back-ish, he's at MacMasters in Canada (to a canadian that's funny because there's a uni named McGill, too. So McGill at MacMaster...anyway), check out his site. You'll find that he's *the* reference when it comes to working out and caring for the spine. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Sunday, July 27, 2008

By Way of Contrast: Lyle McDonald - just the poo, the cynical poo, m'am

On his forum, Lyle McDonald has as his signature, next to the image on the left "i fling poo." What does that mean? It may mean nothing, but it's certainly evocative. It suggests a person who is unafraid of getting to the heart of a matter, speaking his mind, and not taking himself too seriously. A few folks whose opinions i don't take lightly have recently recommended MacDonald's stuff. Trainer extraordinaire Roland Fisher recommended a series of blog posts on an overview of research on EPOC. BJ Bliffert, RKC recommended his book the Ketogenic Diet, which i've just finished reading. Most recently i've cited a post of his in discussing how to figure out what eating "less" means for reducing calories. It finally clicks: poo flinger is all the same guy.

What works about McDonald's work

In each of the above cases, this graduate of a bachelors in physiological sciences digs into the research on an area and brings his own questions to that space to come up with *well-grounded* assessments of material.

Take for instance, the Ketogenic Diet. It is a fantastic overview /reference of what a diet that strips out carbs does to the body. It looks at why/how this approach to diet has been used (and misrepresented) over the decades. McDonald makes clear in it that he is not trying to persuade anyone to use the diet, but to explain how it works, and how its variants work for people to decide if this approach may be helpful to them.

One of the passages in the book i treasure is about the research used to synthesize the effectiveness or not of the diet.

The basic premise of the ketogenic diet is that, by shifting the metabolism towards fat use and away from glucose use, more fat and less protein is lost for a given caloric deficit. Given the same total weight loss, the diet which has the best nitrogen balance will have the greatest fat loss. Unfortunately a lack of well done studies (for reasons discussed previously) make this premise difficult to support (p63).

These statements are really cool: they take head on the fact that there are no well done studies to support that more fat in particular is lost with this metabolic shifting diet. That might seem to be a show stopper - in other words, why continue to discuss this approach if the ostensible reason for carrying out the diet - preferential fat loss - isn't there?

Likewise McDonald takes on the arguments about greater caloric deficit from being on such a diet, and then works through how none of the reasons proposed for such an argument stand up.

And finally, after all the physiology is addressed, McDonald goes through what a diet actually is in terms of considerations like metabolic rate, weight loss vs fat loss and so on. If knowledge is power, this is a powerful presentation. And it's one that's 10 years old.

McDonald clearly situates his interest in the diet based on the effects it had for him:

I became interested in the ketogenic diet two and one-half years ago when I used a modified

form (called a cyclical ketogenic diet) to reach a level of leanness that was previously impossible using other diets. Since that time, I have spent innumerable hours researching the details of the diet, attempting to answer the many questions which surround it. This book represents the results of that quest.

As such, this is an incredibly useful volume, and i certainly recommend it as a great way to get up to speed with what ketogenic diets are, how they work, where they're contra-indicated, etc. We are ten years further on in research in nutrition. The basic findings however haven't changed according to a recent survey of the literature. A calorie is still a calorie thermogenically, and fat loss only reults from caloric deficit, but why some diets seem to work better than others is still an open question.

The Ketogenic Diet was written in 1998, and is different in presentation from the 2005 Ulitmate Diet 2 in one particular: lack of references. McDonald says that he doesn't use them anymore in the books because regular readers could care less; readers who don't like what he has to say aren't going to be persuaded by any number of references (indeed), and those who know the area will be able to figure out the references. That makes me a minority: i like the references, but i'm not an expert in these nutritional domains so can't always find the references myself. Oh well.

Coda

Here's the thing: McDonald describes himself as both passionate about his interests in training and nutrition, and cynical. That's a healthy combination. From his bio page:

People often get frustrated with me because they will ask me a question and typically get an answer of 'It depends'. Because it does. In the lifting and nutrition world, it's most typical to see people get married to a single concept and defend it for all people under all circumstances. whether it's high-carb or low-carb dieting, high volume or high-intensity training, or the never ending free weights vs. machines or compound vs. isolation exercises debate, the message is the same 'There is a single correct answer in terms of how to eat or train and I have it. Now give me money.'

So I'm a little cynical but I can't look at training or diet or the myriad aspects of human physiology that simplistically. The appropriate training for a 35 year old female newbie who has never performed competitive sport before is not the same as what's appropriate for a 22 year old athlete; a beginning powerlifter (or any athlete for the matter) shouldn't be trying to copy what guys with 15-20 years of training experience behind them are doing. Whether machines or free weights or compound or isolation exercises are 'optimal' depends on the individual, their previous training, their current training, their goals and the remainder of their workout. It can all potentially fit into a given workout scheme, depending on the circumstances.

The same goes for diet. The optimal diet for competitive cyclist performing 2 hours per day or more in the saddle won't be the same as for a sedentary couch potato, or for a bodybuilder or powerlifter. Optimal can only be defined in a context dependent way: what is optimal under one situation isn't optimal under another.

At the same time, I find that a lot of folks get too wrapped up in a million and one details that they tend to miss many of the fundamental principles of training or diet.

A training program must provide progression, overload, recovery and few other things to be ideal; what approach to progression, overload, and recovery are optimal for a given individual under a given situation will depend on the circumstances.

A fat loss diet needs to meet certain requirements to be correctly set up in my mind, that includes below maintenance calorie levels, protein intake and essential fatty acid intake. Beyond that, issues of how many carbs, or how much dietary fat, meal frequency and timing all depend on the circumstances.

Is such a philosophy flinging poo? if so i need to revisit my understanding of poo. In the meantime, if you don't have a copy of the Ketogenic Diet for reference, then check out the series on Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC) to see a great example of a ballsy engagement with the research, common myths, and a cynical mind can bring to a pretty good training question.

We might not all want to be or need to be physiologists, but most of us perform better when we know why something works; it also helps when we need to fix it. Well-founded work like McDonald's contributes to confident material for the DIY training toolbox.

We might not all want to be or need to be physiologists, but most of us perform better when we know why something works; it also helps when we need to fix it. Well-founded work like McDonald's contributes to confident material for the DIY training toolbox.Hmm: Cat in the Hat with I can read it all by myself, and Mr Poo's I can read the Research all by Myself? Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Monday, July 21, 2008

Review of the "Science" claims of the Warrior Diet

This post is what some would consider long. That's because there's a lot of material to cover. If you want to cut to the chase, however, just scroll down to the Summary section towards the end of the post.

Prologue

My motivation for this investigation is so many RKC colleagues whom i respect recommend this diet often.

When i first started looking at the description of the diet and its rationale, the descriptions jarred with what i had been learning about nutrition, and so i sought out health and nutrition experts for their insights.

When i first started looking at the description of the diet and its rationale, the descriptions jarred with what i had been learning about nutrition, and so i sought out health and nutrition experts for their insights.I would also say that, as any scientist or researcher would, there's a lot we don't know about the how's and why's of the way we work. If this diet works for some folks, that super. I pick no bones with that. My concern is that the rationale ascribed to why it works seems problematic.

Background

I freely admit i am a rationalist for matters physical. While i am also a critic of scientific positivism, i do find that science provides some pretty effective means for getting at how things work. For instance, while presidential candidates for the republican party were asked this past year if they "believe" in evolution, i will say no, i do not "believe" in a theory, but as a theory it's got a lot of good evidence to back it up. A heck of a lot more than the alternative.

Over the past year i have been investigating the science of nutrition, in so far as my non-chemist eyes can explore it. To that end, based on a post by David Whitely, a respected Sr. RKC, pointing to John Berardi's precision nutrition, i investigated that program (after looking at a host of others) and thought, yes, this approach has the most complete goods. Indeed, the folks who regularly chat on the PN forums are scientists in the field, practitioners, registered dietitians, graduate students in kinesiology and related practice, as well as trainers. In other words, folks who know this stuff and work with athletes and regular folks on a regular, rigorous basis.

Now, while i personally practice the Precision Nutrition habits approach to nutrition, i'm also very much attracted to kettlebells (KB's), and how the work with KB's has been described by Pavel Tsatsouline. Over at the main meeting ground of practitioners of this style of KB is a nutrition forum. Another name for it could be the Mostly about the Warrior Diet forum. In his books, and occasionally online, Pavel explicitly states that this is the diet he likes and follows, while also stating that he's not a nutrition expert, but that it works for him. So with a source like that to point the direction, why not check it out?

Before encountering Pavel, however, i encountered Clarence Bass of Lean for Life and the best looking 70+ year old on the planet (next to sean connery, of course). And Bass's reasoned assessment of the Warrior Diet was a little less accepting, in particular on the point of training on empty.

Hofmekler couches his diet in terms of "natural wisdom" and the instinctive eating cycle of the ancient warrior. He also includes the concepts of freedom -- to eat as much as you want in one large meal (as long as you follow the Warrior Diet rules) -- and spirituality. "Many people have long believed that one can only experience a deep spiritual awareness when fasting," Ori writes.While Bass's review was written in 2001, current research still largely supports Bass's assessment. It's this: that training fasted does have draw backs especially for recovery post training. While some positive effects of fasting have been found, none of them are the soul domain of fasting. All of them can be supported with good nutrition and exercise. In other words, one doesn't need to go hungry to live well and thrive.

I don’t quite see it that way, however. In my view, the Warrior Diet is basically an extension of the concept of training on empty. Ori says controlled fasting 16-18 hours a day "guarantees hours of fat burning." (See our FAQ page for a discussion of training on empty; I don’t buy it.)

Hunger, says Hofmekler, "triggers the Warrior Instinct." It makes you "sharper, more alert, more energetic, and more adventurous." Still, if you must, he says it’s okay to have some "live" raw fruits or vegetables, and even a small portion of protein during the "undereating phase." (For my review of the research on fasting, see "Fasting" and "Starve & Get Fat" in chapter 7 of The Lean Advantage 2." Most authorities agree: Fasting is generally a bad idea.)

The Terms and Claims about the WD: sources used

If the research shows that fasting is not necessary to achieve a host of good things for health, what are the claims of the WD?

It's important to note that Hofmekler's WD text make it hard to see how claims about how food is processed by the body are backed up since there are no direct references to any particular research or text books. When i raised this point in a discussion, a colleague pointed me to another book by the Hofmekler called Maximum Muscle Minimum Fat: The Secret Science behind Physical Transformation (MMMF for short) that was supposed to provide the science behind WD claims. In MMMF, there are indeed a number of books and articles listed at the back of the volume, but none are referenced within the chapters of the book, so it's not possible to unpack which references Hofmekler sees as supporting which claims.

This non-citation /bibliography-only approach is pretty unusual. Take for instance a diet book like Lyle MacDonald's the Ketogenic Diet(here's a post about his approach to nutrition). Every second line, it seems, has a reference to the article or text used to support the claim being made: what claim goes with which article is clearly indicated. That's basic practice so a reader can see for themselves how the author is building their case. That doesn't happen here. All the more reason i've been grateful to be able to connect with experts in physiology, nutrition, recovery and training to understand these claims.

In investigating this question of claims about the Warrior Diet, therefore, i've turned to the main document Ori Hofmekler, the author of the WD presents to the world about the "science" on the Warrior Diet. These are the science page of the WD site, and the page comparing WD to other diets. These are promotional pages to encourage people to buy the book, so the veracity of their claims is important. I also reference the Warrior Diet book to clarify key WD terms like "undereating," "overeating" and "controlled fast." So, let's start with the concepts, to make sure we're all on the same page, and then go to the "science" claims.

Controlled Fast vs Intermittent Fasting or any other Kind of Fasting

A theme in the WD is fasting. It's discussed a lot, from its alleged religious to physical properties. That would make one think that a good part of the WD is about fasting. Indeed, the "controlled fast" is a key concept in the book. So what is a controlled fast and how is it different from the popular mot du jour "intermittent fasting" or "caloric restriction."

In the IF literature, intermittent fasting is actually NOT eating for a fixed period of time - either within a day or of whole days. As the IF101 site describes:

* Daily Fasting: Typically done every day and only giving the person a smaller eating window in which to get their calories. (for example, a 18hr daily fast would mean someone would only eat every day between the hours of Noon and 6pm). You will see varying times from 15-19 hours for daily fasting.Caloric restriction, it should be noted, is a far more liberal definition: as defined in an overview of IF related research by the Journal of the American Medical Association, it's anything less than "ad libidum" - or less than eating what you want, as much of it you want, whenever you want

* Fasting 1-3x a week: This could also be called alternate day fasting/calorie restriction (for those doing it every other day). This is just fasting of usually longer periods 18-24 hours but only 1-3x a week. Many variations to play with here.

Controlled Fast, Part II: Undereating, Overeating

So where does a controlled fast fit into these points along the eating spectrum of Fasting (no food at all for a given period) on one end and ad libidum on the other?

It's hard to say, explicitly; we need to infer a definition from the WD text. Here's why: Part one is labelled "controlled fasting" but it begins with a discussion of "undereating" as an alternative to fasting which is too extreme, he asserts for most people.

Moreover i believe the best way of going through the Undereating Phase is by following a controlled fast, not a water fast. Controlled fasting is easier to follow and it accelerated detoxification and overall well-being.

This is as close to a definition of controlled fasting we get in the book. Immediately after this, 2e get lots about the alleged benefits of controlled fasting, but nothing specific about what this means. We get instead a discussion of what happens in the body supposedly when we fast, and a whole lot about fear of hunger and various other suppositions about the role of fasting in history. The closest we get to an explicit statement is on p27 in the section "If you find it difficult to adapt." Suggestion 1 is titled "Gradually increase the controlled fasting time" in which readers are told "Start by undereating from morning until noon, and then add an hour or two per day."

Ok, so, effectively we have two terms for the same thing: controlled fasting = undereating. It would seem, therefore, that despite all the preparatory discussion about fasting, controlled fasting is not fasting in the IF sense (going without any food for a given period), but simply eating less, or what Hofmekler calls "undereating." Indeed Hofmekler writes, "On the WD the principle of fasting is based on not eating a full meal during the day"

Intriguingly, the non-full meal during the day is defined as consuming raw vegetables or vegetable juice "with some portion of protein, if needed." Hofmekler is down on protein during the day as it allegedly interfers with letting the body detoxify and "rest." To minimize this "stress" Hofmekler recommends cottage cheese and lean animal protein or almonds instead (p33). In the WD, Cottage cheese, some fresh veg and fruit, a glass of juice is undereating. For many of my colleagues, this mix of protein and carbs (and the fat also contained in say the cottage cheese) constitutes a "full" meal. But if it is not a full meal in the WD sense, what is?

The full meal is presented (implicitly) in the "overeating" phase - or Feast. It differs from the undereating meal as far as i can tell in one way: it adds what it calls "carbs" to the meal.

ASIDE This is another curiosity in the WD: veggies are separated out from "carbs." In the WD only the more starchy carbs like rice and pasta are labelled as carbs, whereas veggies are called "vegetables." But vegetables are a key source of carbohydrates.

Hofmekler in describing the "overeating" makes a number of claims about the order of eating during the Feast meal: start with veggies, then eat protein, then if you're not satisfied, eat what he defines as carbs.

Hofmekler makes a series of unsupported or careless claims about these "carbs" when eaten in a feast (that is, with protein and fat sources) (p82)

1) carbs "create satiety since they naturally boost serotonin production in your brain."

There seem to be two problems with this assertion:

(1) Only starchy/sweet carbs increase serotonin levels (2) they don't produce any serotonin when ingested with protein (ie, at a feast).

First, a technical point, but the GI of a food is the GI of a food; it doesn't change. Second, the rate of digestion of starchy carbs when combined with other nutrients doesn't slow down their rapid availability to the body. This is why nutrient timing approaches (eg, Precision Nutrition, overviewed in this doc) recommend eating starchy carbs in meals that come after workouts, when the body is most sensitive to insulin, and muscle glycogen stores have been reduced by a workout. In this state, the body can best take advantage of the more rapid availability of the glucose available from these starchy carbs for replenishing that depleted muscle glycogen. The factor that facilitates this uptake is the insulin triggered by the presence of the rapid abundance of sugars from these fast digested sources.

If we therefore feel satiety and "relaxed" at the end of a big meal, it's not serotonin; it's the demands of the body to shunt blood to the GI away from our limbs to process food. The full warrior is a fleet warrior?

In the absence of Hofmekler's connecting the dots of research sources to his claims either in the WD or his Maximize Muscle book, i've sought the council of experts in diet to help understand what's being claimed. Here's how the discussion has gone. Again, for this part of the discussion, i'm pointing to material available on the WD web site so it's available to any reader.

Fast to Feast to Fast Metabolism

The first claim on the Science page is that eating a single BIG meal a day will speed up the metabolism.

[W]hen people practice overeating after undereating, their body changes to a more thermogenic and highly metabolized state. The brain receives a signal that it should elevate metabolism in order to burn the extra energy coming from food. On the whole, when one overeats after a controlled fast, nutrients are assimilated at a greater rate, there is an acceleration of the anabolic process of repairing tissues and building muscles, depleted glycogen reserves and intramuscular triglycerides (special high octane fat fuel in the muscle) are replenished, there's an increased secretion of dophamine, thyroid hormones, and an elevation of sex hormones. If overeating is practiced regularly, your body's metabolism will remember this, and while adapting to these daily big meals, it would most likely become metabolically faster and more efficient than before.

A sped up metabolism is a good thing for folks wanting to lose weight because all a fast metabolism means is that we are needing more energy to support the body's activities [metabolism explanation 1, metabolism explanation 2]. That energy comes from fuel - or the food we eat or the energy we have stored as fat (and the sugars we have in our muscles).

There are a bunch of claims in this section of the WD site about metabolism, so let's take them one at a time:

when people practice overeating after undereating, their body changes to a more thermogenic and highly metabolized state. The brain receives a signal that it should elevate metabolism in order to burn the extra energy coming from food.

Okay, food of any kind has a thermogenic effect because it takes energy to break it down (see Power of Food section). Some foods take more energy to break down than others. Protein takes more energy than carbs, for instance. So, actually, eating more frequently keeps your body's metabolism revving over a longer period of time, because each time you eat, especially if you eat whole foods, you're using goodly amounts of energy to consume it. So the argument for overeating meaning higher thermogenic value doesn't quite fly there. Let's move on.

On the whole, when one overeats after a controlled fast, nutrients are assimilated at a greater rate, there is an acceleration of the anabolic process of repairing tissues and building muscles, depleted glycogen reserves and intramuscular triglycerides (special high octane fat fuel in the muscle) are replenished, there's an increased secretion of dophamine, thyroid hormones, and an elevation of sex hormones.Wow this sounds good: after starving, when you eat, you get more benefit - better nutrient uptake; better muscle building; more hormones, more more more. But more and better than what? According to what research?

On the other hand, i can point to considerable work that shows that frequent feedings do in fact have tremendous benefit for hormone levels, metabolic rate and tissue repair. Here's one example by Benardot at Georgia State University that has shown that increased feeding frequency (5 meals vs. 2 meals) at the same daily caloric load, improves Lean Body Mass (LBM), decrease Fat Mass (FM), *increases resting metabolic rate,* better controls blood sugar and insulin, decreases blood triglycerides and more (download a pdf on this research).

So the claim about the benefits of fast/feast really haven't been met here based on accepted science. Indeed, at least as far as i could find, the counter arguments seem to hold. What we get to, ultimately, is an assertion not of fact but of of Hofmekler's "belief" in a particular approach:

Scientific studies indicate that there's a correlation between our metabolism and how many calories are consumed per day. However, as far as I know, no studies have been conducted on the correlation between our metabolism and the amount of calories consumed per meal. I truly believe that the amount of calories consumed per meal is the bottom line.Actually, there's a lot of research about amount and kind of food consumed per meal, like Bernadot's above, and the various papers cited in it, as well as comparisons between ad libidum feeding and fasting, as overviewed in the JAMA article. There's also considerable experience with what's known as calorie and carbohydrate cycling for both fat loss and lean mass gains.

What is well know and accepted science is that caloric restriction slows down the metabolism; it does not speed it up. In particular, with respect to Hofmekler's claims about a big meal speeding up the metabolism again after undereating, the contrary seems to be indicated, as stated by Registered Dietician (difference btwn RD and Nutritionists) and PhD student G. Fear, "[a]fter underfeeding, your body is primed to store incoming calories as fat, not to ramp up metabolism to burn them."

Some may say "malarky: i've been following the warrior diet and i'm losing weight." Bottom line, if you've cut out crap, are eating less during the day and one sit down meal at night, and are losing weight, at one level you're just taking in fewer calories. And it really doesn't matter what approach you use: if your input is less than your output (the fuel you need for burning), you lose weight. Your loss gains may be improving as well because you're working out more, which also means more fuel demand from adaptation of various systems etc. So, if you're losing weight it may not be down to any particular magic about undereat/overeat, but in cleaning up input and having reduced caloric input vs the same or greater caloric demand.

It's also interesting to note that in what is termed the "science" page for the WD site, the basis for the author's assertions about his approach get down to belief about how his system works. In science, sometimes such a belief is couched as an hypothesis: a claim to be tested. How have Hofmekler's claims/beliefs been tested? Let's hold that one, too, and move onto another assertion.

More on Metabolic Acceleration

Let me give you an example of how adaptation works. People can walk for two hours every day without noticing any improvement in muscle, strength or speed, but if they sprint for only five minutes a day, they will most likely notice improvement in both strength and speed . So, it's not necessarily the length of time spent exercising, it's the intensity of the exercise. Coming back to the subject of diet, the question remains: Is it the intensity of the meal that will dictate your body's metabolism? My answer is yes. That's the way I experience it.The above represents an effort to create an analogy to suggest how one thing works can be used as a model of how another thing works. Teaching by analogy is part of a great pedagogic tradition. But the first question in designing the analogy would be to test if the analogy itself is accurate for the point being made?

The assertion that people can walk for hours a day and notice no difference is absolutely false. The research done, for instance (and this is just an example) with de-conditioned or elderly populations getting them into Mall Walking has made significantly measurable improvements in their cardiac health and reported weight loss progress. Recent research showed in fact - from a large sample population - that inability to walk a 1/4 mile a day (what a very slow person could do in 15 -20 mins) is a predictor of mortality and poor health in the elderly. Greater benefits have been shown *potentially* in elderly populations that mixed their regular walking pace with some bouts of more intense walking ( i don't have the details on how "intensity" or duration of interval was measured or set, but it's still walking, not running).

To continue with the analogy, with respect to sprinting for FIVE MINUTES EVERY DAY and the contention that someone would notice improvements in strength and speed, let's check that out. What's a sprint? It's an all out effort for either time or distance. For folks in the kettlebell or crossfit space, that may also be equivalent to doing the Tactical Strength Challenge Snatch test - all out numbers with a kettlebell in five minutes. Now imagine being asked to do that *every day.* In Pavel Tsatsouline's Enter the Kettlebell, the bible of kettlebell initiation (review here), Tsatsouline says to practice one's snatch only once a week.

Likewise, when training elite athlete sprinters, they may only be asked to sprint - actually sprint - once or twice a week because it's so taxing on the system. That is, the body needs the rest of the time to recover from that effort. If doing that every day with an elite athlete would be at best damaging, imagine what that would be like for our unconditioned or elderly population?

In other words, far from the author's contention that this sprinting approach would lead to strength and speed gains, repeated practice and research demonstrates that the results would be the exact opposite of what the author suggests. So if the Warrior Diet is indeed like (trying to) sprint every day, then it would be seen as both unsafe and therefore a poor recommendation on those grounds alone.

Next Claim - Overeating is a deep instinct

The Warrior Diet is the only diet that explores the advantages of overeating. Let me say something to all those who overeat and then feel guilty. You feel guilty because you didn't know that a deep, primal instinct drove you to overeat. An instinct that we have most likely inherited from our late Paleolithic ancestors who were night eaters, cycling between periods of famine and feast (undereating and overeating). Many people binge late at night when exhausted from a rigid, obsessive, daily self-control. That's usually the time when inhibitions are broken down and the alleged "demons" come out. But these are not demons. If you know how to use this instinct in the right way, it can work for you instead of against you.I'm not sure where the author gets the evidence to suggest that our Paleolithic ancestors were "night eaters" or that this is a good model, or not. Let's face it: how would we know? The only remains that will keep over a long period of time are bone and, if you're really lucky, seeds (my undergrad summers were spent on prehistoric sites - believe me i've catalogued enough fish otoliths to have a sense of this - but don't take my word for it: check in with archaeologists who look at diet (paleo diet critique 1; journal special issue 2)). Anything therefore about our long long dead ancestors is largely speculation (that's anthropology) on thin evidence. To be able to claim with any certainty we ate at night is in that light, rather astounding.

So who likes to binge at night? Perhaps folks who grab a quick cup of Joe and something sticky as they run out the door; sit at their desk, maybe grab a sandwich of dubious quality and don't eat anything else till they get home. No kidding they're hungry. Not sure who would argue, howerver, that that approach to eating is a sign of warrior like organization, preparedness and practice. Most of us would call that rather the approach of the couch potato, who far from being svelt is over weight.

Frequent Feedings vs The One Big One

We now hit what seems to be the key rationale behind Hofmekler's approach to eating: rest. On a comparison with other diets page, Hofmekler says that really, frequent feedings are just too hard on the system - it never gets a chance to rest and detoxify, and that just stresses the pancreas and is a fast track to GI distress, whereas the warrior diet is about "daily detoxification and enzyme loading" Here's the quote:

The frequent-feeding system (followed by many people today) is where you eat relatively small, frequent meals throughout the day. Those who advocate frequent feedings say that it puts less pressure on the digestive tract, allegedly keeps sugar levels stable. And, especially for physically active individuals, it allegedly enables them to ingest more protein throughout the day to further build muscles.Well, hmm. The assertions about the rationale for frequent feedings are without reference. The system of frequent feedings with which i'm familiar, Precision Nutrition, makes no such claims as those asserted in that first paragraph. You can either check out the rationale for the approach at the PN site or read literature like Bernadot's, cited above, that looks at nutrient timing relative to what we know about optimizing resources to our bodies when they need it, throughout the day.

So, setting aside that point, let us consider the rest of Hofmekler's claim is that

The huge disadvantage with the frequent feeding system is that your body never gets a break to detoxify, to recuperate, and to let the pancreatic system rest. Additionally, when you deposit material so often, without giving your body enough time to detoxify, you basically deplete your body's pool of enzymes. This often results in compromised digestion - especially of proteins. Indigestion weakens the immune system, and if this goes unchecked, leads to disease

A large percentage of those who practice frequent-feeding no longer have a healthy feeding cycle. It's no wonder why so many today suffer from digestive disorders, constipation, weight gain and related diseases. These problems are so pronounced that the companies who sell drugs to help people become "regular" make a bloody fortune.If we set aside for a moment the lack of any evidence offered either to define what frequent feeding is in practice, or support that people who follow a frequent feeding regimen suffer any of the ailments Hoflekler ascribes to them, let's focus on the main assertions:

The Warrior Diet is built on daily detoxification and enzyme loading as key components. If you practice this diet, you'll eventually reach your own natural cycle and should be able to sustain prime health and increase your resilience to stress and disease. This makes the Warrior Diet radically different from all conventional diets today.

- that frequent feeding means the body can't "detoxify" and "recuperate"

- frequent feeding means that enzymes are depleted

- digestion is compromised

Now, you could likely provide a falsifiable argument - and it would be this -when you frequently feed, you acutely decrease the production of digestive enzymes.Taking that challenge, i could not find anything that suggested frequent feedings decrease digestive enzymes, or that over time there is a drop off in enzyme production. I did confirm a few things, however, and that's that eating a great big high glycemic meal does have a negative impact on the pancreas. As G. Fear, explains it:

Another would be when you frequently feed over long periods of time, you eventually see a drop-off in production of digestive enzymes in response to feeding.

These can be tested and falsified. Pop over to medline and see if you can find anything on these. If so, then you've got some evidence supporting the Warrior Diet's claims. If not, then you've got no evidence and are on pretty shaky scientific ground

The biggest stress to the pancreas is high glycemic meals, or the large spike in blood sugar following a gorge! Over time, high glycemic loads and the high production of insulin do two things, first they dampen the body's response to insulin (insulin resistance). So the pancreas, already pushing to keep up with your "feasts" now needs to try and make more because the rest of the body isnt listening so well. Thats when you have superhigh insulin levels yet still high blood sugar (the first stage in type 2 diabetes). Eventually, the pancreas wears out and insulin drops off to virtually nothing, which doesn't matter much because the insulin doesnt work anymore anyway, because the body is too resistant. (Thats why type two diabetics dont get insulin shots, it wouldnt help them like a type 1).This is not to say that folks on the WD eat high glycemic meals when they feast - i just point this out as the one core research related, scientifically supported issues around the pancreas being pushed beyond capacity: it's not frequency of meals; it's regular, high GI input. I now have a better understanding of the causes of Type II diabetes, but no proof that digestive enzymes fall off, or that the pancreas is any more stressed or not with frequency of feedings. I only have examples of research as cited earlier that show the overall benefits. To the particular claims about frequent feedings causing us to deplete the "pool o enzymes," Fear states that little could be further from the case:

First, your body does not run out of digestive enzymes. You have way more enzymatic capability than the amount of food you could possibly consume. Studies have been done to see just how much people could absorb, and the subjects were still absorbing fat at virtually 100% when they were force fed 500 g of fat a day. Your body is very efficient, it has evolved to get every calorie and nutrient out of what you eat and not waste it.

[...] Anyone who says the pancreas can't keep up with multiple meals is not up to date on how the GI tract works [...] the pancreas produces digestive enzymes, but they are stored in the gallbladder until you eat. Its essentially a storage tank, so when you do eat, the gallbladder contracts and squirts the enzymes into your gut. The pancreas is making enzymes all the time and they just get stored until needed. So eating often just makes the galbladder contact more often, but the pancreas is doing its same old job. Eating one big feast a day - gallbladder contracts once, and stores up the rest of the time. Your pancreas will not really have an issue either way.

So, the claim about frequent feedings vs single meals on the pancreas and digestive enzymes also doesn't really bare up under scrutiny of what we know of the science.

When asked about multiple vs a single large meal, Carter Schoffer of Precision Nutrition (a frequent feeding approach to nutrition) stated

Aside from MSG-laden Chinese food, how long after a feast of meal do you stay full? For hours and hours, right? You go to bed stuffed and wake satiated. What's happening here? Well instead of the food waiting in your fridge for it to be consumed, digested and absorbed, it's waiting in your GI tract to be tended to.Some of the WD practitioners i've spoken with say that they do not pig out in their evening meal - it's size is simply more substantial to what they eat during the day - more "a regular sized meal" - so they mayn't be suffering the extreme GI overload described above, but Schoffer's points are worth consideration.

How is this any less of a burden to your pancreas? Does it not follow that it's a considerably greater burden to unload a dump truck load of food as opposed to shovel fulls? Is this not seen by (a) how long one remains stuffed (b) how gassy and bloated one becomes after a large meal and (c) how large and unprocessed the stool is?

Your digestive tract is simply overwhelmed - rather than paced along like any good manufacturing/construction process. You don't dump the entire truckload of cement and stones on masons, you cart and trough it to them at a rate they're able to handle, and take advantage of, without feeling overwhelmed.

[...]

As I've said countless times before, we eat food for more than just the kcal value. We eat food for overall nutrition. The body does a pretty good job of storing the macronutrients by way of a big belly and bottom and a decent job of storing some vitamins and minerals (in your fat belly and bottom) but it does a poor job of storing a heck of a lot of other nutrients. When you're not eating throughout the day, you're depriving your body of these nutrients and you can't make up for these with a massive bolus of food because your body will have more than it knows what to do with. What follows is a mass exodus of otherwise beneficial nutrients.

Intermittent Fasting: Live Long and Prosper - like Mice?

There is one more claim over on the Science page that cites one 2003 study that shows that mice on intermittent fasting had all sorts of benefits from increased longevity to reversal of diabetes. There's only speculation about how this will work, in the long run, for humans.

Why Hofmekler cites this one study of all that work done on IF is a bit of a mystery, since there are studies involving human participants in IF. Likewise, since as we've seen, the WD is not about fasting as understood by any other group using this term: it does not mean avoiding any food input for a period; it means "not eating a full meal." So it's unclear why this study would be seen to support Hofmekler's approach. A skeptic might suggest that this seems like misdirection of some kind.

It's important to note, though, since Hofmekler raises fasting both in the book and on this page of the site, that intriguingly, there is nothing that one can point to that fasting provides in terms of benefit that exercise and good nutrition do not also provide, and without the known down sides of fasting, as this review shows.

Working Out Empty

The last claim i'd like to consider is with respect to claims around working out empty. Again, i know a number of martial artists who prefer this - and that's fine - but they do not make claims that this is either nutritionally optimal, or an approach they would use for heavy training. Hofmekler on the other hand, does make assertions about why this approach is excellent for training and weight loss. In the book Hofmekler states that

post exercise particularly on an empty stomach your insulin receptors are at peak sensitivity...your body is now ready to consume large amounts of food without gaining weight

So, have some protein post workout, he argues.

This is the claim where Bass, quoted at the top of this article, parts company with Hofmekler. Likewise the research on working out in a fasted state (not an empty stomach) highlights the problems with this approach:

Improvements in insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance (except in women undergoing ADF), bodyweight/bodyfat, blood pressure, blood lipids, and heart rate are commonly cited benefits of IF & CR.Another source to consider is the Fasted Cardio round table for just how far this idea tracks. On the flip side, just because you've worked out does not mean you can eat anything you want without gaining weight. Let's get real. Not all exercises either burn a lot of fuel or tax our muscle reserves of fuel. Does exercise prime you to take on replacement fuel? if at sufficient intensity, yes it does. But does that mean you can eat anything and not gain weight, fasted or not? No. If you consume more than you burn you gain. That's all.

• § All of the above benefits can be achieved by exercise, minus the downsides of fasting.

• § IF and CR have both been found to have neuroprotective effects by increasing BDNF levels.

• § A growing body of research shows that exercise can also increase BDNF, and the degree of effect appears to be intensity-dependent.

• § Based on the limited available data, resistance training performance, especially if its not particularly voluminous, might not be enhanced by preworkout EAA+CHO.

• § Despite equivocal performance effects of pre- or midworkout EAA+CHO, it minimizes muscle damage that occurs from fasted resistance training.

• § Immediate preworkout protein and/or EAA+CHO increases protein synthesis more than fasted resistance training with those substrates ingested immediately postworkout.

• § It’s possible that a partial fast (as short as 4 hours) before resistance training can negatively impact muscle protein status.

Also, as science about nutrition has shown for eons, "fat burns in the flame of carbohydrates" - there's a long explanation for this all about the krebs cycle, pyruvate and ATP, but bottom line is: with sufficient fuel in the tank, even more work can be done, and more fat burning can take place. Running on empty is sub-obtimal for training. Again, this doesn't mean that people can't train or don't train on empty and feel ok doing it. To claim that it is the optimal way to prime the body to take on fuel, or is an optimal approach to training is not supported by Science.

We can say that science doesn't know everything; science gets stuff wrong. well, alright, then fair is fair: the points made here are that Hofmekler himself appeals to science or pseudo science to back his claims for why his diet not only works, but is superior. The purpose of this article has been to see if those claims either have merit or support - if, indeed, there is any "science" to support Hofmekler's claims *as* science.

Summary: Sans Science

It seems that, taken one at a time, the arguments Hofmekler puts forward on his web site as "science" to assert that One Big Meal a day has many benefits specific to its approach alone is not there. Indeed, as we have seen, some of its claims, such as those about carbohydrates, enzymes, pancreatic stress/rest and detoxification, seem to be problematic at best, if not simply wrong.

But just because the alleged "science" claims about the diet may be wrong, unsubstantiated or confused, does that mean there is anything particularly unsafe or wrong with the diet itself of smaller meals during the day and a large meal at night?

Going back to RD G. Fear, she replies

I wouldnt say its harmful at all to consume all your calories in one big sitting if someone prefers to do that over eating them frequently. I'd consider it optimal for retaining muscle mass and boosting metabolism to eat more often, but if you arent taking in too many calories, you can certainly lose weight that way.In other words, it's possible to get into a place where the body is comfortable eating one meal a day, and a few folks over at the DD forum have been doing this for awhile. A few. I've encountered more folks, however, who's practice seems at odds with pretty loose relative to the averred approach. I haven't asked them about this directly, so i won't speculate. But i will observe that some long time advocates of the approach at a recent event certainly had a lunch of protein, veg and starchy carbs that would rate as a "full meal" by Hofmekler's definition, and was then followed that evening by what appeared to be an equally adequate full meal dinner. While i said i wouldn't speculate, such an observation might lead one to think that there is something more attractive in the name than in the complete observation of the practice.

In terms of subjective reports of wellbeing.... its true they could adjust and not feel as hungry. [Assuming that one is NOT eating during the day; is in fact intermittent fasting] being in a fasted state all the time, your blood sugar could be very stable, with the liver meting out glucose [as fuel, rather than getting it from in coming carbs - whether veggies or other -mc ] to keep you going.

Some people have a tendency to get hypoglycemic when they dont eat for long. I think [that is] influenced by 1) consuming a pretty low carb diet 2) eating frequently, so my metabolism is HIGH, 3) eating relatively small meals, so I'm probably not storing up loads of liver glycogen.

Someone who eats more carbs and trains their body to tolerate the daylong fast might feel better... because the liver enzymes which break down glycogen to release blood glucose upregulate. So WD devotees dont "bonk" while waiting for their next meal.

Epilogue

In Michael Pollan's In Defense of Food, he writes "who am i to tell you how to eat?"

Likewise, this article is not intended to tell practitioners of the Warrior Diet to give it up. As the summary of the IF review paper states in its conclusion:

It's given that personal goals and individual response are the ultimate navigators of any protocol. Therefore, training and meal schedules should be built upon individual preferences & tolerances, which undoubtedly will differ. However, the purpose of this article is to arm the reader with the facts, so that opinions and anecdotes can be judged accordingly. Personal testimony is invariably biased by the powerful placebo effect of suggestion, and sometimes by ulterior agenda. Science is perched on one end of the epistemological spectrum, and hearsay is on the opposite end. As the evidence clearly indicates, IF is not a bed of roses minus the thorns - there are definite pros and cons.Similarly, the purpose of this article has been to set the scientific claims in the context of attributable, researchable science: to ask the question, are the claims described as "science" using scientific descriptions. "science"? As has been shown, those claims are simply not supported by known science.

In the world of fitness, recommendations for improving performance and body composition often gain blind acceptance despite a dearth of objective data. This is common in a field where high hopes and obsessive-compulsive tendencies are united with false appeals and incomplete information. In order to be proven effective beyond the mere power of suggestion, supposed truths must be put through the crucible of science. Drawing conclusions from baseless assumptions is a good way to get nowhere - fast.

What we do know to be the case: if we eat more than we burn, we gain weight; if we eat less, we lose weight. This effect is not specific to the WD. Because there are people who do practice the WD and claim to find it beneficial to them, why it works, therefore, is for reasons other than those claimed as science by the author, and which is not. These reasons may range from convenience, psychology or what Mike T Nelson, RKC, calls "metabolic flexibility"

As Kris Aiken, BAHon, CSCS, Precision Nutrition network coordinator suggests however, when asked why a particular diet seems to work, he asks "works compared to what? In terms of not eating at all, it will be better. IMO the body is a very resilient organism and people can often succeed in spite of, and not because of what they do. "

It may well be that the WD is effective because of something rather than in spite of something else; that the method is better than simply being "not harmful," and that it is more than adequate for some people to train as well in a depleted state; that the convenience of eating less, or the sense of spiritual or psychic reward of feeling hungry or of controlling one's self with respect to food intake has a higher reward than on a different plane than providing sufficient fuel to get optimal value from a task. It may also be that we learn new things about the genetic components of food that will offer some insight into this WD approach that we don't have now.

In the meantime, however, the claims cast as science made about how and why it works as cited above are at odds at least with what i've been able to discover about the science underlying what is known about those processes. So if you're doing the WD, and you like it, great - just know that the reasons for why it works for you may not be those that are asserted by its author. Any mistakes in the presentation of this critique are mine, and i'm keen to understand where they might be.

If you would actually like to consider another approach than the WD - perhaps just by way of comparison - maybe explore what frequent feedings or peri-workout nutrition is - there are options: you can check out at least the one example i know of for frequent feedings tested in use from regular folks to elite athletes, and that's precision nutrition. If the thought of managing many meals is one too many, there's also any of Clarence Bass's excellent books on eating whole food. There too, the rationale for the approach is clearly spelled out - and as clearly referenced.

As Michael Pollen writes, eat food, not too much mostly plants. And let me add, eat for fun, love, pleasure - and health.

There's good science in that.

UPDATE Sept 09, thanks to Richard Chignell for passing this along: studies of real IF (like eat stop eat) vs the one big meal (like WD) . Also in the Related Post below on alternatives, i've talked with enough colleagues now who find IF, even weekly 16 hour fasts to be hitting the sweet spot for them.

I've also talked now with a number - not a lot, about a dozen - personal trainers who are in great shape and have told me that they did the WD to burn fat, did, and got mean. I was intrigued by that report. Since they didn't quite care for themselves they changed their approach.

In this recent article on diets and support for successful change in eating practice, i recommend a multi-phased approach. Why not first take the time to get to know - really know - how you and your body react/benefit to different foods under different conditions - and i suggest a few ways to explore that.

Then, once you know about yourself in that regard, play around with whatever style of eating you wish, from ketogenic to IF - just do it with a base of self-understanding, and some strategies to be consistent enough to get through any initial adaptation crises.

Related Posts

- alternative approaches to WD: this critique of 12 week diet plans like P90X offers a lot of 'em

- alternative ways to think about nutrition: what the heck is sustenance?

- a more trad IF approach, colleague recommended: eat stop eat

Friday, July 18, 2008

Balancing Focus with Diversity with Humility

There's a great heuristic in nutrition that says to know if we're eating right, get lots of colour on the plate. If it's all monotone shades of white to yellow, then we know there's something - possibly a lot - missing. If it's vibrant in colour and texture, happy days, we're likely hitting all the bases.

In nature, we observe the same thing: we talk about rich ecosystems vs monocultures. Where diversity exists in the system, the ecosystem thrives. Monocultures on the other hand, are far more vulnerable, less able to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity.

In fitness we also apply a kind of diversity towards progress, whether this is swapping around a variety of compound exercises throughout the week, or periodizing the intensity of the day's efforts, variety is important to stave off plateaus or injuries from overuse, etc.

To go back to the nutrition analogy, it seems this same principle of diversity would apply to food for thought: lots of colour on plate means a healthy, nutritious, well balanced diet. That if our intellectual diet is monotonous, singular, lacking diversity, then we are ill nourished. As with monocultures, we are less adaptable; more vulnerable.

And yet while many folks know about nutritional diversity or diversity in their fitness programs, intellecutal diversity seems a foreign concept. I've been struck of late by the number of people who have read either just one book on a topic, or just one author on a subject and speak ex cathedra, as if because of this one book, one author, they now know the field and can proffer opinion. They will defend their corner vigorously, adamantly on the basis of this monoculture of information.

This phenomenon, it seems, is the opposite side of the coin of what sifu mark cheng recently described about RKC's who after the certification, instead of focusing on the basics themselves, and teaching them in strict form, become diversified too quickly, try to bring in too many moves. The consequence that recently manifested itself at an RKCII cert, apparently being that many instructors were not competent to perform the core curriculum.

In this case, we are seeking to master a skill in order to teach it, and so focus and practice practice practice are critical. Rannoch and i have disccused this too: the movement from the repetition of the skill so many times that it's into the bone where its expression becomes art. Will Williams performance of the kettlebell front squat, i've written about, is just so.

In the Tao is the Ten Thousand Things

How resolve on the one hand diversity is critical for health and well being and on the other a singular focus is critical for mastery?

It seems, again to go back to Mark's post, that humility is critical in each case. If we are humble before a topic, we will know that we are pretty ignorant, and need more than one book, one lecture, one web page, to come to grips with area of interest. IF we have read just one thing on a topic, we acknolwedge the source: according to x, this is what's happening, rather than stating "this is what's happening" Why? i teach my students this as basic scholarship: unless you are a recognized expert in a domain, your opinion is just that; an opinion. Why should your readers trust your opinion?

At least if all you have is one source, and you provide your readers that source, they can go check it out for themselves, where they might get more information. what will they get if they come back to you, assuming this is your knowledge, rather than the re-presentation of someone else's? But if all you have is one source, and you engage with someone else who may well have more expertise than you, know more (having read broader and deeper; practiced further and longer), then at least listen, and maybe learn something.

As Mark states in his post:

To use a martial arts analogy, it's as if a relatively new blue belt suddenly decides that his bollocks are too big for his belt and he decides to go & pick a fight with a bunch of brown and black belts. The smackdown is comin'.

It's not just that the brown/black belts know more than the blue belt; they have greater mastery of the same things the blue belt knows. The best have worked with many teachers; have studied broadly. Not all at once, but over time.

This still feels like i'm talking about a contradiction:

on the one hand, focus on mastery which means practice on a limited set of things rather than a vast array; on the other hand i'm talking about diversity of knowledge. What keeps coming to my mind is to know when to shut up.

Progress is most often linear.

In school, we learn the basics of math, then of geometry before getting to calculus. The basics are needed before getting to more advanced forms of expression. Once those basics are mastered, conversations can begin with other mathematicians about how problems may be solved. Techniques are shared, new techniques are built upon these; innovations happen. A mathematician interested in one particular problem will read a wide range of papers related to just that one topic. There is the diversity around the singularity, and there is growing expertise.

As another example, in computation, artificial intelligence work is informed by biological systems research, complexity theory and more recently gaming theory from economics. One problem to solve, influenced by multiple perspectives/disciplines.

Likewise, a martial artist who has a devastating punch will likely have studied many techniques from many masters on the punch to distill it into one perfect practice.

In these domains, if we do not have that rich expertise, whether practical or intellectual or both, we would not presume to tell someone else who knew as little or less than ourselves either how to do something or, with confidence, how something works. Our experience is thin; our practice shallow.

What's my point?

I guess that we might do well to own our own limitations better and speak/walk with more humility about our own knowledge/accomplishments. This is perahps why many of us put our credentials on our blogs/sig files, so that people can judge our statements and practice on their merits. Not that these credentials are a guarantee of excellence - hence why most have ongoing renewal/rectification processes. And where certifications do not exist, all the more reason to acknowledge sources and walk with humility, till our work speaks for us.

Clarence Bass is an excellent example of someone who is not a certified expert in health or nutrition: he is an intelligent person who has made his reputation by carefully presenting research in plain language, and checking out findings in one source against those of another; of talking with multiple experts, and from this putting together exceptionally valuable syntheses of this material. It's based on the demonstration of his analyses and syntheses of others' work, and the demonstration of his own practice and insights that has made him a respected expert in the community. He's my hero & inspiration in this regard.

This post all started as a rant about people who seem to have read one book or article and then speak on a topic as if they were experts.

My main point was that knowledge is not so thinnly founded.

Science and Wisdom both demand repetition across diversity before asserting a General Case or Accepted Practice. Do multiple respected sources agree with this position? Where is the disagreement? What are the conditions in which this is true vs where it is not?

My secondary point is that we need to feel unsatisfied with our intellectual fodder if we're interested in a topic and stop at one source - whether that's one book, one author, one site, one monoculture. We need to challenge ourselves to be open to multiple sources on our one topic.

The gift of a good teacher of course is to help chart the progress from the one to the other. The gift of a good student is rich curiosity, with respectful, humble, delightful engagement. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Thursday, July 17, 2008

The Anti-Goal and First (things First) Principles

You are trying get moving, not launch a rocket.

So many people seem to struggle with this. If the conditions aren't optimal they simply abort.

Give me 10 minutes and a kettlebell. Not so hard.

For those with workout OCD, it stops progress in it's tracks. The requirement to have everything in it's proper place prevents them from so much as breaking a sweat. This anabolic anxiety permeates everything they try to do. Plans are great but if you are fixated on a having all the ingredients for particular outcome you are missing "all that heavenly glory".

Rannoch's observation got me wondering if one of the limiting factors that contributes to this OCD training effect is The Goal. This is not to say that goals are bad at all, but they can become mental mine fields when not treated appropriately. The voice in the head becomes:

I *have* to do this kind of workout today because of this GOAL i have for date X, and if i can't train that way because of whatever (including just being pooped) then what's the point? anything "less" than the prescribed load, volume and moves is just failure (to serve teh goal), so why bother? I'm such a loser, aren't i?

That's kind of voice sounds irily reminiscent of procrastination/perfectionism. When the goal feels too daunting to achieve well, just leave it to the last minute and blame the fact that you didn't have enough time; or worry worry worry the little details (see "getting intrigued") rather than the big picture. Fear, fear of failure, of therefore being a failure is the thing in either case, and so inertia, it seems, sets in.

Goals have a lot to answer for. In a sense, perhaps, as Stephen Covey might put it, it's a trust issue with ourselves: if we don't meet our commitment to our goals, we break faith with ourselves till we give up on ourselves. Frequently we may coat the cost of this failure by "getting intrigued" (described towards the end of this post on complexity ). Where we say oh this isn't right; that isn't right; i'll do it tomorrow when the moon and the stars are aligned and i feel better.

Goals have a lot to answer for. In a sense, perhaps, as Stephen Covey might put it, it's a trust issue with ourselves: if we don't meet our commitment to our goals, we break faith with ourselves till we give up on ourselves. Frequently we may coat the cost of this failure by "getting intrigued" (described towards the end of this post on complexity ). Where we say oh this isn't right; that isn't right; i'll do it tomorrow when the moon and the stars are aligned and i feel better. For myself, this failure can be a particularly trying place to be if i can look back and see past successes, dedication, effort. So what's wrong with me *now* that that's not happening?

Maybe a better question to ask is what needs to be in place to re-establish relations with ourselves to feel that success of having done it than that dread of another day gone and the Goal further dishonored.

Maybe some of us who have already figured out that working out is important for our health, our spirit, our commitments, have to be to get to the headspace where the Real Goal is first to remember how to keep faith with ourselves and second to find a path back to doing that in terms of our fitness, health, well being. Perhaps it's as simple as re-setting the goal temporarily to something we KNOW we can accomplish, perhaps just to move something today. To move ourselves, a kettlebell, a rock - through space, perhaps multiple times in a row or throughout the day, and that that *is* a good thing, not only because it really *is* better than nothing, but because we said we would and we did.

Progressively, repeatedly, soon, the groove to that larger goal may just return, when we build our own confidence back up that we can keep our commitments to ourselves and we can trust ourselves with larger challenges.

In the interim, while simply keeping the commitment to move something in a day, we can give ourselves the space to figure out what may be acting in our lives right now such that we've been falling off the wagon; over complicating it, and what perhaps NOT to repeat once we get back in the groove such that we wind up back in the pit - if that's a recurring place to be.

A book i find helpful in this space is Stephen Covey's First Things First. The book talks about the importance of understanding why we *do* things, not in terms of some schedule like life as a perpetual to do list, but in order to define and move from principles. Don't prioritize your schedule; schedule your priorities is a phrase from the book. How do we determine our priorities? Based on what principles? what is our compass?

These questions apply here, in working out, too, i think. If we're not doing what we know to be right and good for our well being, and our ability to serve those we love, then something's askew, no?

Asking such questions can be a rather profound process. Covey suggests a number of ways to engage what can be very challenging work, where not working out is a symptom whose more profound causes may need investigation.

But in this meantime of engaging that process, and assuming that part of it may just be this loss of faith with ourselves to follow through on our commitments to ourselves, here's to everyone who's having a moment of doubt and self criticism. Let's give ourselves a break and all promise to do one push up, one swing, one pistol - one something - together in five minutes, and build on that.

Congratulations to us, we did it. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Rannoch is Profound

To others he's the RKC from Scotland.

If you haven't read his blog, you own yourself the pleasure of the text. It's so straight, clear and no bullshit, it's like a field in the morning after the rain. a breath of fresh air. It doesn't matter if he's talking about training or dining, it's real (i like real).

If you read only one (well, other) blog today, hope you'll check out Rannoch's. Likely, you'll be back.

And if you like what you read, perhaps you may consider buying a t-shirt. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

More Inspiration: David Swenson and Ashtanga

This is the closest public video i can find: his First Series DVD has no audience/performance; it's a really nice walk through of the first series. Even if you don't want to do ashtanga, it's a great watch.

Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

What does "eating less" mean?

Recently i've been part of a lot of discussions about weight loss and calories being calories (or not) and dealing with Real People who are very frustrated at being slightly overweight, but having a heck of a time getting the last 5-10 pounds down.

No matter what your school of thought, we know that to lose weight you have to input fewer calories than your system needs to maintain your weight.

We also know however, that some people seem to lose weight faster than others (i don't mean some people are skinny and stay skinny no matter what they eat, i mean *lose weight*). Some hypothesize that it's the type of diet - privileging fat or protein over carbs, etc etc. But recent literature suggests that the differences in approach aren't particularly significant - they're noise.

If that's the case, and we assume that people can indeed lose real fat (not water, which dropping out carbs does right away, but FAT) while still eating real food including a balanced range of macronutrients (fats, proteins, carbs), how do we know what the right "less" is to ask people to eat, or to not eat, as it were?

Over where i write for geeks to help them get fit and think about food more nutritiously, i've got a piece comparing three methods:

- the drop 500cals a day to lose a pound a week,

- the drop 20% from maintenance and

- the it's all relative to your fat method.

My caveat as always in this space is that before thinking about counting calories, you need to know something about the composition of those calories (protein/carbs/fats) and about how to put those ratios together to work for you. Approaches such as Precision Nutrition's habits (here's an overview) don't count calories at all in the initial phases. There, it's get right with good food habits first, and see where that takes you. Doing anything else first is just getting intrigued without a foundation.

It's like what Pavel Tsatsouline talks about in his seminar with Charles Staley around powerlifting: why would someone who's a neophyte lifter worry about whether they're going to be a grinder in their deadlift or a speedster? they have to get the skill of their strength first.

Same thing here. So i offer this idea about calculating "less" ness more as a way to understand or think about a process, not as a how to until those basics are in place. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Friday, July 11, 2008

Green Tea - good for more than what ails ya

Weight Loss & Anti Oxidants

Thermogenesis is the body creating heat - burning energy - by raising the metabolic rate above normal. Green tea has been shown to be good at this - safely.

So that's one good thing about green tea for health and diet. Another is that it's a powerful anti-oxidant, and that is supposed to be a good thing in the battle with aging/free radicals/heart disease and possibly some cancers (here's an overview).

The thermogenic and anti oxidant effect is largely courtesy of epigallocatechin gallate found a bit in chocolate and in other tea types, but highest concentrations are in green tea. A 99 study in the Journal of Clinical Nutrition claimed 43% increase in thermogenesis in adults with 90mg dose of per day.

Drinking about a liter of green tea a day will get these kinds of doses (32oz). That's the same as slightly less than three cans of coke. Or the amount in a typical gym water bottle.

If drinking tea is not your bag, there are alternatives like green tea in powdered pills or tablets. Also, some green tea supplements take care to get the caffeine out of the mix, too - and that is a good thing. Another product is from Tea Tech that Jackie Chan is delightfully fronting: Tea Tech Green Tea, tea with a kick. This is 'instant' tea with a difference: it contains 100mg of those ECGCs. So there's your thermogenic effect right there.

How much a day?

If you're taking green tea in pill form, Registered Dietician Ryan Andrews suggests no more than 300mg a day. Some recommend that, since Green Tea has a thermogenic effect, it's optimal to take it especially before working out so that it's giving a helping hand to fat mobilization that takes place when working out.

What Kind?

Some folks like just to grab some green tea bags, brew 'em and be done with it. If this is the only way you've had green tea, which can taste a wee bit bitter - what i imagine boiled hay would taste like - you're in for a treat if you try loose japanese green tea.

I am in no way a green tea guru (there must be a term for this like someone who knows tons about wine), but generally speaking there are nine kinds of Japanese green tea (and these kinds are big categories). I'm just going to mention the ones i've experienced and really enjoy.

Down at the worker end of loose green tea is Genmaicha. This type of green tea has brown rice kernels in it, and sometimes, what's very nice, some Matcha - the fine powdered green tea used in the Tea Ceremony. It's called Matcha-iri genmaicha. Now, i really really like this tea with the Matcha and the rice. It gives the tea a kind of grainy, meaty taste that is very satisfying, and the color (unlike the stuff in the bags) *is* green. In USD a nice genmaicha can be had for about 4USD/100g.

If you don't care for the kernels, well you can get plain old Sencha. These are steamed, dried early tea leaves, and it's this steaming rather than Chinese green tea frying that i personally prefer. Nice taste; easy to prepare.

If you decide you like Japanese green tea, you can go for the Uber Green Tea, Gyroku - another Sencha, but treated quite differently than other senchas. It's pale, delicate and requires attention to brew and drink. You give it that attention because it's dam pricey. Here in the UK, 17 quid for 100 grams is mid range.

How to Prepare

Let's skip the special prep for the Gyroku and talk about the other senchas. You can get yourself a japanese green tea pot - a pot that will have a screen in it so that you can pour out the tea as soon as it's ready into wee cups. That's nice.

The Gear. But if you want to make a less delicate more coffee-drinker like batch of tea, ideally you'll want something that lets the tea leaves expand in the water while they're steeping. Some folks use a coffee press, but that's na sa good an idea: it lets the leaves continue to sit in the water after they're supposed to stop steeping. An alternative is a tea pot designed to let the leaves expand, and where the leaves can be lifted out. Bodum makes such pots that can be had at discount houses like TK Max from time to time. The material: ceramic or glass.

Some Japanese groceries also sell stainless steel strainers that can sit on the lip of smaller (60-65mm) tea pots. Easy peasy. UPDATE - even better for letting the tea expand and dealing with leaves: this post on a super tea infuser.

Ah yes, once the steeping is done, LIFT OUT THE LEAVES. Why? well one reason is they can be used again at least once, and sometimes twice; another reason is that the taste of the tea can be botched if left to over-steep.

The Water

A critical part of making that lovely green tea green is the water. Putting it through a filter like a brita is a nice thing to do to tap water. Not essential, but nice (bottled water in most places/circumstances is evil, so don't even think about it :> ).

The water to hit the leaves needs to be cooler than boiling. So how do you get the temperature right? Boil the water. G'head. Just leave the kettle to sit for 2-5 minutes - you'll figure out what works for your type of tea.

Time to Brew

Depending on the tea, it may need to steep for 90sec or 3mins - it ain't long. When it's done just right, you'll see that lovely green jade color. It *looks* like GREEN tea. remember: lift out the leaves once the steeping is done.

And the taste.