Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Shoulder ReHab pt 3: Only Skin (or Fascia) Deep? Yes, It's a money move

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Last week, in part 2 of the right shoulder rehab story, we looked at how a nerve running past the liver and into the diaphram might be adding to shoulder noise. That was - for me - a very new idea in looking at right shoulder rehab. This week, we're back stepping from the edge of the new to some of the lessons learned in my left shoulder revelation might apply on the right and accelerate right side recuperation. In particular, we're focusing on the Skin and Fascia - and their movement.

One of the key things i learned in that dramatic (to me) treatment session on the left shoulder was an object lesson in the site of pain is not the source of pain. Frickin Doh!. Muscularly, this meant that while i was having a big biceps tendon issue, the thing firing up the biceps was around the extensors and brachioradialis. We'll look more at muscle investigation and muscle work, next time.

But a related lesson to this muscle work was skin and fascia work: that sometimes if we don't assess and work with the skin and fascia - while doing all the other good movement stuff - we miss an opportunity to accelerate a path to performance increase (pain decrease).

Only Skin Deep - or a little deeper.

So, today, looking at lessons from the left shoulder and my actions from that on the right shoulder, lets consider the stuff above the muscle that connects the muscle, guts, bones, etc. In other words, let's look at the both the skin and under skin, the fascia.

Sometimes working these layers can be an incredible way in to performance improvement, as i learned with my left shoulder and have seen again with my right.

A little about Skin. Skin is called the biggest single organ of the body. Like the heart is an organ, the skin is an organ. It's also the biggest component of an entire system in the body, the integumentary system (one of 11 systems we run). On the organ side (like the heart that pumps blood or lungs to refresh our air supply) the skin is far more than a single function organ. It is deeply involved with managing homeostasis: it contributes to regulating system temperature, and also protecting us from abrupt temp changes; it is a barrier to infection; it is a waterproof casing; it is a protective wrapper to more delicate tissue beneath it. The skin is where the action is for getting vitamin D out of the sun.

On top of these roles, the "cutaneous distribution" of nerves means that we feel things through the skin that affect our position in space, and how we respond to our space. We feel heat, cold, pressure, and so on at the skin layer. Many nerves that have motor functions also have sensory functions - and a cutaneous distribution - so sometimes just working at the skin level of a muscle's nerves or related nerves can have a powerful effect. How deep is the skin? How hard can you press without your cuticles going white? That's all skin stuff.

How the skin feels is important. Signals go in; signals go out. There are directions to skin movement that tell us a lot about its healthy or not movement, too.

A little about Fascia. Beneath the skin layers are fascial layers. The role of the fascia is a new country for discovery. Many folks are coming to the fascia via the book Myer's Anatomy Trains. Myer's work seems highly influenced by much earlier German work by Hoepke in 1936, Das Muskelspiel des Menschen - showing that the under wrapping of the body the layers that connect muscles and groups of muscles to each other along with other tissue, organs, bones, is a neurologically active wrapping. That means it's responsive. Nerves innervate tissue for a purpose; nerves run into the fascia. What's happening?

Some very interesting contemporary work at Ulm University in Germany at the Fascia Research Project is focusing on the active contractility of the fascia. Muscles contract. These researchers, in particular Robert Schleip, are looking at how fascia has active properties to act *actively* in a muscle-like way (their pdf describing this model of fascia).

Indeed, part of anatomy trains is that the fascia is plastic: it can get wound (as in fascia-as-sheet(s), hence fascial winding) in a direction that has effects along the line of its connection through the body, pulling the rest of the body along to comply with this dissonant shape. Thus, the fascia must be likewise be unwound (often manually is the suggestion) to get back to an appropriate form to enable appropriate mechanical function.

That view kinda presents the fascia as more like playdough: the fascia takes the shape of the stresses upon it and holds that shape.

The Fascia Research Group suggest that fascia is more (re)active in its responsiveness to movement. Likewise they suggest that there is a nociceptive function to fascia - that when it is damaged, it may connect to musculoskeletal pain (pdf review).

If fascia is actively engaged in our bodies' structural integrity and it's responding actively to movement issues, and if there is this direct component around nociception, then perhaps working actively with the fascial layer in movement for improving performance is a good idea.

Skin and Fasica - so what? Well, it's part of a path. How many folks when they go see a physio or chiro have that specialist check the movement of the skin or fascia layer around the nerves of a given muscle firing up a pain cry? Or, even if there's no pain, but say one's shoulder press is seemingly stuck, think to check skin/fascial barriers to multi-directional movement?

Turns out that often a little bit of checking of skin/fascia restrictions can yield a whole lot of improvement in range of motion, performance, decrease in pain. It's worth knowing if your coach or carer or therapist works with skin/fascia in a pain free way.

No Pain, No Pain. Why do i say pain free? After all, some folks LOVE a massage that just reefs into the deep tissue (i.e. muscle) and just makes one grit one's teeth until the muscle or whatever just lets go. Like pounding one's head against a wall, it feels so good when it stops. Well, yes, that's

No Pain, No Pain. Why do i say pain free? After all, some folks LOVE a massage that just reefs into the deep tissue (i.e. muscle) and just makes one grit one's teeth until the muscle or whatever just lets go. Like pounding one's head against a wall, it feels so good when it stops. Well, yes, that's  one way to freak out the nervous system. But pain - and that's what that kind of presure can be - causes startle. Startle's a threat response; it's a shut down/protective response. And who or what performs better under threat, while freaking out?

one way to freak out the nervous system. But pain - and that's what that kind of presure can be - causes startle. Startle's a threat response; it's a shut down/protective response. And who or what performs better under threat, while freaking out?

It seems there are alternative ways to work with skin and fascia that achieve the same ends - even actively to get good motor learning - that do not induce more startle, more threat.

If you're curious about why such pain free tissue work is "just as good as" the stuff that makes one weep, i'd recommend Eyal Lederman's Sciene and Practice of Manual Therapy . It has a lovely discussion of how tissue moves, and how working with that - actively and necessarily without pain - creates positive performance benefits.

. It has a lovely discussion of how tissue moves, and how working with that - actively and necessarily without pain - creates positive performance benefits.

A part of such an active (vs manual) approach to engage with the skin or fascia - once a direction of effective action has been detected - a next step may simply be to bring active awareness to that part of the body.

Enter Kinesio Tape.

There is a well known process in physical therapy that talks about this kind of skin based stimulation - just rubbing gently on an area to bring awareness to that area. Sometimes that's all one needs to help sort out a movement issue. It's a powerful tool for helping address muscular amnesia, for instance - where a muscle just doesn't fire when it should - the body has developed what's become known as sensory motor amnesia, as Thoman Hanna puts it.

Sometimes one needs simply to bring a little awareness to an area to get it to turn on again. With my left shoulder, working with skin and fascial movement assessments showed that there was relief and improved range of motion with just a little bit of a shift in an area of fascial action. How was this tested? Gosh - gently holding the fascial layer in that direction while moving: is range of motion improved? Pain go down? Great, let's bring some awareness to that area.

With my right shoulder, knowing from various Z-Health courses like 9S: Strength and Suppleness and from T-Phase a bit about skin stim, muscle activation and various neural connections, and remembering my own left side rehab, i started exploring myself if there were directions in moving or stimulating either fascia or just skin in my shoulder or arm or neck area (going with all the nerve pathways that can affect the shoulder) that allowed greater range of motion/less pain. Yes. There were. Quite a few.

And so also using some knowledge of the application of kinesio tape

And so also using some knowledge of the application of kinesio tape - an amazing stuff that supposedly works with the skin/fascia to support movement (what they call lifting) in a given direction - i applied a wee bit of it to an area with appropriate directional testing, and then immeidately retested my arm. Improvement. I'll take it.

- an amazing stuff that supposedly works with the skin/fascia to support movement (what they call lifting) in a given direction - i applied a wee bit of it to an area with appropriate directional testing, and then immeidately retested my arm. Improvement. I'll take it.

I've made the soggy error of laying down a bit of tape after testing direction only to have missed the spot. This stuff does not like being relaid. So ya grit your teeth and chuck that expensive bit of therapy assist and try again. Measure twice as they say. It's this retesting immeidately that is SO important.

Over the next couple days i had a wee pattern of tape - about three pieces - deployed with this test/retest approach to see what was working to support improved movement/performance. The tape stayed on for three to five days, and seemed to help deliver what was on the tin.

Active Skin Stim? The kinesio tape - it seems - whether it's designed to work this way or not - seems to have the effect of bringing a low level but constant awareness to an area where skin level direction of movement has an effect. It seems to offer a way to get reps in - to help the skin and perhaps underlying fascia move in a more optimal direction - or perhaps being taped towards a given direction that tests well is just opening up better neural awareness so that Good Things Happen.

Take Aways: Respect the Fascia

For me, working with just the fascial/skin layers was not the total killer ap for my left shoulder or my right, but it was a HUGE contributor in opening up performance by especially opening up the range of pain free movement in my shoulder. Checking out how your coach/trainer/therapist works with skin/fascia as part of their (active) rehab work is a Good Idea. If they don't include such consideration, maybe you want to find someone who does - pain free.

It's remarkable to me that sometimes such a gentle stimulation can have such a potent and immediate effect.

My caveat in this space is as always: test and reassess immediately. Knowing how to apply this stuff is as nothing to knowing how to test *immediately* whether the application has had a positive effect.

Next time, promise: exploring end range of motion work with bands for super potent rehab and performance restoration like you would not believe.

Other Posts in this series:

Related posts:

Related Resources

- here are some awesome cadaver dissection images of the muscles of the shoulder Tweet Follow @begin2dig

|

| Superficial dissection showing fiberous fascial layer of shouler, head, neck. |

But a related lesson to this muscle work was skin and fascia work: that sometimes if we don't assess and work with the skin and fascia - while doing all the other good movement stuff - we miss an opportunity to accelerate a path to performance increase (pain decrease).

Only Skin Deep - or a little deeper.

So, today, looking at lessons from the left shoulder and my actions from that on the right shoulder, lets consider the stuff above the muscle that connects the muscle, guts, bones, etc. In other words, let's look at the both the skin and under skin, the fascia.

Sometimes working these layers can be an incredible way in to performance improvement, as i learned with my left shoulder and have seen again with my right.

Aside: i KNOW this stuff - about skin and fascia work as part and parcel of muscle/joint/visual/vestibular work - what i'm describing below is the kind of work i do regularly with clients. Somehow, sometimes, when we're looking at ourselves we forget our own deliberate practice. Pain, i think, makes us stupid. So i offer the following thoughts for all of us coping with our own pain who mayn't be thinking straight about it.

A little about Skin. Skin is called the biggest single organ of the body. Like the heart is an organ, the skin is an organ. It's also the biggest component of an entire system in the body, the integumentary system (one of 11 systems we run). On the organ side (like the heart that pumps blood or lungs to refresh our air supply) the skin is far more than a single function organ. It is deeply involved with managing homeostasis: it contributes to regulating system temperature, and also protecting us from abrupt temp changes; it is a barrier to infection; it is a waterproof casing; it is a protective wrapper to more delicate tissue beneath it. The skin is where the action is for getting vitamin D out of the sun.

|

| skin deep: it's actually pretty deep. |

On top of these roles, the "cutaneous distribution" of nerves means that we feel things through the skin that affect our position in space, and how we respond to our space. We feel heat, cold, pressure, and so on at the skin layer. Many nerves that have motor functions also have sensory functions - and a cutaneous distribution - so sometimes just working at the skin level of a muscle's nerves or related nerves can have a powerful effect. How deep is the skin? How hard can you press without your cuticles going white? That's all skin stuff.

How the skin feels is important. Signals go in; signals go out. There are directions to skin movement that tell us a lot about its healthy or not movement, too.

| |

| Myers's anatomy trains a popular intro to fascial layers, connections and movements |

Some very interesting contemporary work at Ulm University in Germany at the Fascia Research Project is focusing on the active contractility of the fascia. Muscles contract. These researchers, in particular Robert Schleip, are looking at how fascia has active properties to act *actively* in a muscle-like way (their pdf describing this model of fascia).

|

| Fascia Between Muscle Fibers |

That view kinda presents the fascia as more like playdough: the fascia takes the shape of the stresses upon it and holds that shape.

The Fascia Research Group suggest that fascia is more (re)active in its responsiveness to movement. Likewise they suggest that there is a nociceptive function to fascia - that when it is damaged, it may connect to musculoskeletal pain (pdf review).

If fascia is actively engaged in our bodies' structural integrity and it's responding actively to movement issues, and if there is this direct component around nociception, then perhaps working actively with the fascial layer in movement for improving performance is a good idea.

Skin and Fasica - so what? Well, it's part of a path. How many folks when they go see a physio or chiro have that specialist check the movement of the skin or fascia layer around the nerves of a given muscle firing up a pain cry? Or, even if there's no pain, but say one's shoulder press is seemingly stuck, think to check skin/fascial barriers to multi-directional movement?

Turns out that often a little bit of checking of skin/fascia restrictions can yield a whole lot of improvement in range of motion, performance, decrease in pain. It's worth knowing if your coach or carer or therapist works with skin/fascia in a pain free way.

No Pain, No Pain. Why do i say pain free? After all, some folks LOVE a massage that just reefs into the deep tissue (i.e. muscle) and just makes one grit one's teeth until the muscle or whatever just lets go. Like pounding one's head against a wall, it feels so good when it stops. Well, yes, that's

No Pain, No Pain. Why do i say pain free? After all, some folks LOVE a massage that just reefs into the deep tissue (i.e. muscle) and just makes one grit one's teeth until the muscle or whatever just lets go. Like pounding one's head against a wall, it feels so good when it stops. Well, yes, that's It seems there are alternative ways to work with skin and fascia that achieve the same ends - even actively to get good motor learning - that do not induce more startle, more threat.

If you're curious about why such pain free tissue work is "just as good as" the stuff that makes one weep, i'd recommend Eyal Lederman's Sciene and Practice of Manual Therapy

A part of such an active (vs manual) approach to engage with the skin or fascia - once a direction of effective action has been detected - a next step may simply be to bring active awareness to that part of the body.

Enter Kinesio Tape.

There is a well known process in physical therapy that talks about this kind of skin based stimulation - just rubbing gently on an area to bring awareness to that area. Sometimes that's all one needs to help sort out a movement issue. It's a powerful tool for helping address muscular amnesia, for instance - where a muscle just doesn't fire when it should - the body has developed what's become known as sensory motor amnesia, as Thoman Hanna puts it.

Sometimes one needs simply to bring a little awareness to an area to get it to turn on again. With my left shoulder, working with skin and fascial movement assessments showed that there was relief and improved range of motion with just a little bit of a shift in an area of fascial action. How was this tested? Gosh - gently holding the fascial layer in that direction while moving: is range of motion improved? Pain go down? Great, let's bring some awareness to that area.

With my right shoulder, knowing from various Z-Health courses like 9S: Strength and Suppleness and from T-Phase a bit about skin stim, muscle activation and various neural connections, and remembering my own left side rehab, i started exploring myself if there were directions in moving or stimulating either fascia or just skin in my shoulder or arm or neck area (going with all the nerve pathways that can affect the shoulder) that allowed greater range of motion/less pain. Yes. There were. Quite a few.

|

| Kinesio Tape - the origintal: accept no substitutes |

I've made the soggy error of laying down a bit of tape after testing direction only to have missed the spot. This stuff does not like being relaid. So ya grit your teeth and chuck that expensive bit of therapy assist and try again. Measure twice as they say. It's this retesting immeidately that is SO important.

Over the next couple days i had a wee pattern of tape - about three pieces - deployed with this test/retest approach to see what was working to support improved movement/performance. The tape stayed on for three to five days, and seemed to help deliver what was on the tin.

Active Skin Stim? The kinesio tape - it seems - whether it's designed to work this way or not - seems to have the effect of bringing a low level but constant awareness to an area where skin level direction of movement has an effect. It seems to offer a way to get reps in - to help the skin and perhaps underlying fascia move in a more optimal direction - or perhaps being taped towards a given direction that tests well is just opening up better neural awareness so that Good Things Happen.

Take Aways: Respect the Fascia

- For some, some level of guided skin or fascial support is sufficient to let them "fix" their issue. I've seen this numerous times with mine and others clients, and it always amazes me.

- This layer or suites of layers covering our bodies and interconnecting other systems (muscular, skeletal, visceral) is not to be underestimated or forgotten in treatment.

- Learning how to work with these layers - a big focus of zhealth t-phase as one example for where such education happens - can lead to potent results.

- Sometimes, as an awareness assist, a bit of kinesio tape it seems can help the body learn this new movement pattern at the skin/fascial level. Kinesio tape is an active movement support. Sometimes, that tape isn't necessary, but it's a nice tool when it is.

For me, working with just the fascial/skin layers was not the total killer ap for my left shoulder or my right, but it was a HUGE contributor in opening up performance by especially opening up the range of pain free movement in my shoulder. Checking out how your coach/trainer/therapist works with skin/fascia as part of their (active) rehab work is a Good Idea. If they don't include such consideration, maybe you want to find someone who does - pain free.

It's remarkable to me that sometimes such a gentle stimulation can have such a potent and immediate effect.

My caveat in this space is as always: test and reassess immediately. Knowing how to apply this stuff is as nothing to knowing how to test *immediately* whether the application has had a positive effect.

Next time, promise: exploring end range of motion work with bands for super potent rehab and performance restoration like you would not believe.

Other Posts in this series:

- Rehab Journal Part 1: overview of a journey

- Rehab Journal Part 2: the phrenic nerve and thinking other site/source thoughts

Related posts:

- The Shoulder: Scapula engineering

- Shoulder Engineering: the g/h joint

- tendon - opathies and eccentric contractions for repair

- Fish oil and being anti-inflammatory.

- One less rep: the differnece between injury and success?

- What's a movement assessment?

- Active vs Passive Therapy - what's it mean and why care?

Related Resources

- here are some awesome cadaver dissection images of the muscles of the shoulder Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Right Shoulder Active Rehab part 2: phrenic nerve and the liver shoulder?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Welcome to Part 2 of my right shoulder rehab log.When my right shoulder started to hurt, it happened after doing a few ordinary kettlebell presses on the right side. I have no idea what i did to kick off this result - it didn't even feel like the usual uh oh the arm went too far back - something's pulled. It was just pain. This post is about the seemingly strange connections from the liver to the shoulder via the phrenic nerve - and how getting that connection may reduce pain and improve movement.

To cut to the chase after the first few days of nothing seeming to calm down what felt like an inflammatory response - that initial owie of restricted motion and soreness - i went looking for some ideas. Since the nervous system is the governor of the body, and the body responds quickly to threats to it (as in the arthrokinetic reflex), it seemed like an idea to look for any nerve responses about the shoulder.

Previously when i was working through the mystery of pain in my left shoulder, UK Osteopath Andrew Bellamy in the comments of that post suggested to keep in mind any mid neck issues (C5-C6) since this is an area where nerves running into the rotator cuff muscles can get squished. When neck nerves get squished they certainly can refer out to the shoulder.

Previously when i was working through the mystery of pain in my left shoulder, UK Osteopath Andrew Bellamy in the comments of that post suggested to keep in mind any mid neck issues (C5-C6) since this is an area where nerves running into the rotator cuff muscles can get squished. When neck nerves get squished they certainly can refer out to the shoulder.

To quote Andrew's Comment

Cervical and Brachial Plexus. Quick aside about nerves: the spine is the origin point for nerves. Nerves send the signals to power anything in our bodies that moves or has signals moving through it. Veins, muscles, tendons, lungs, brain for instance, all have nerves. Most of these nerves are associated with what are known as spinal segments - areas around a given vertebrae. Nerves come off these spinal segments quite often with thicker branches that split into finer strands.

Cervical and Brachial Plexus. Quick aside about nerves: the spine is the origin point for nerves. Nerves send the signals to power anything in our bodies that moves or has signals moving through it. Veins, muscles, tendons, lungs, brain for instance, all have nerves. Most of these nerves are associated with what are known as spinal segments - areas around a given vertebrae. Nerves come off these spinal segments quite often with thicker branches that split into finer strands.

These larger nets of nerves are referred to as Plexi. The nerves that connect with our neck, shoulders, arms and hands are part of the Cervical (from C1 to C5) and Brachial Plexus, spinal segments from C5-T1 (T1 is the top of the thoracic spine). It's the shape of these plexi that give the nerve fibers, well, give for being able to stretch, compress, torque and move with the body. Amazing engineering.

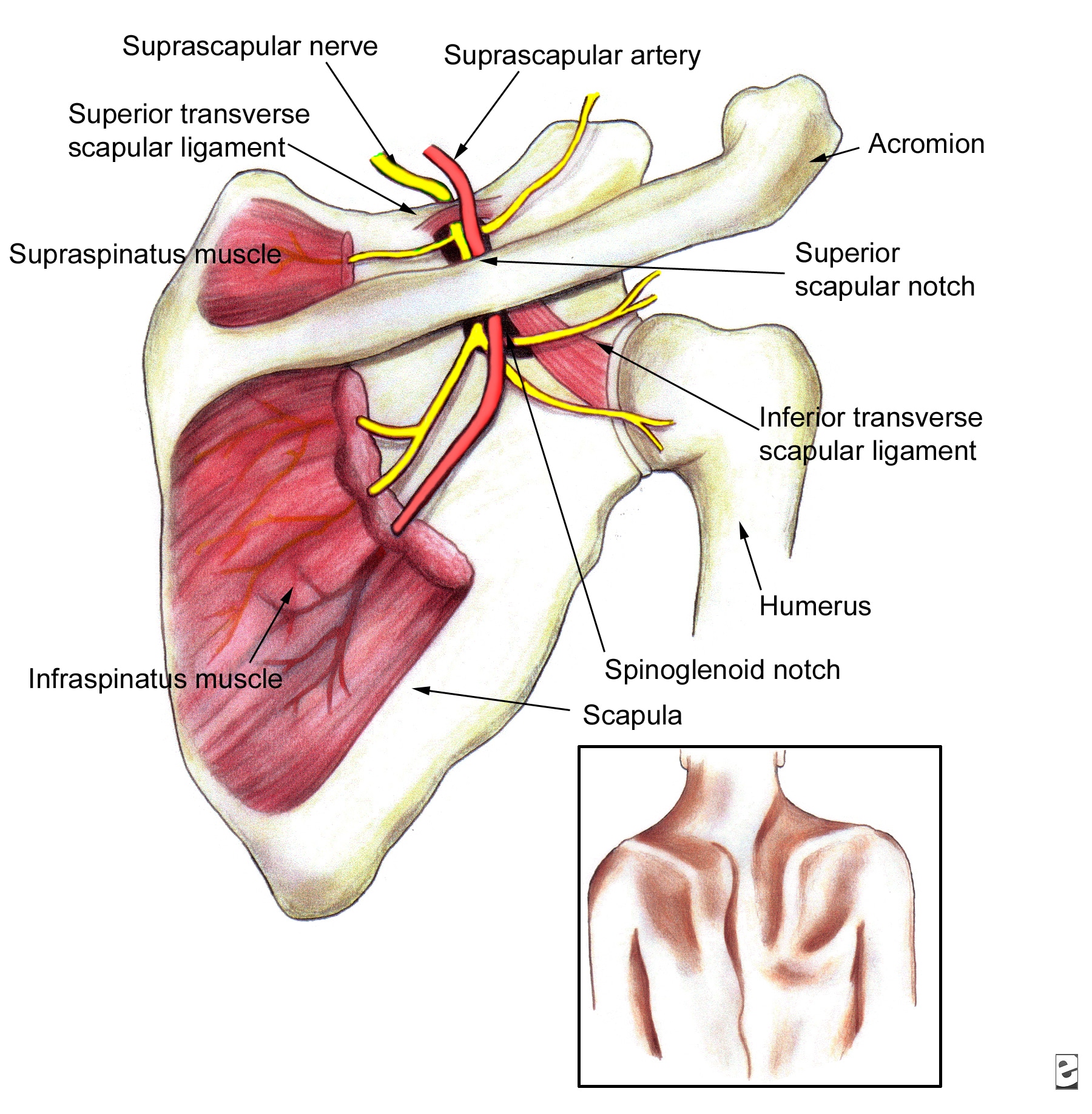

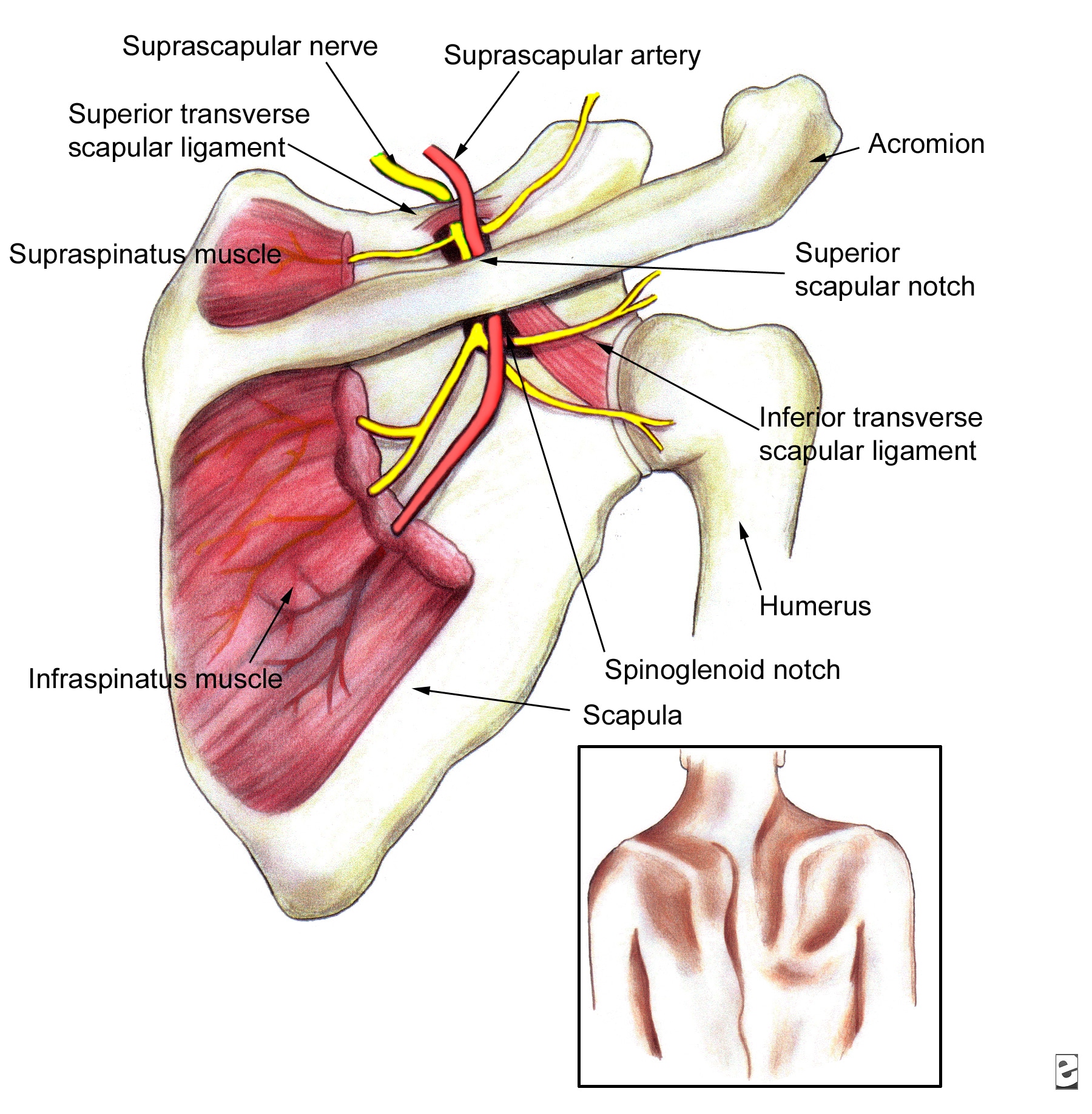

From Suprascapular to Phrenic Nerve: the site of pain not the source of pain

It was thinking back to Andrew's comments that made me wonder about a nerve squish troubling my shoulder. There are some good neurodynamic drills that can help release the suprascapular nerve if that's what the impingement is; there are lots of great mobilisations for the head and neck too. These weren't quite doing it for me.

There's a book by Barral and Croibier on the Peripheral Nerves

There's a book by Barral and Croibier on the Peripheral Nerves . I pulled that one down to have a look to

. I pulled that one down to have a look to see what i might be missing in nerve world. If you're interested in how the nerves work in our bodies, from how they're fed to how they can be manipulated for improving movement, this is a well illustrated and interesting text.

see what i might be missing in nerve world. If you're interested in how the nerves work in our bodies, from how they're fed to how they can be manipulated for improving movement, this is a well illustrated and interesting text.

Starting with the area of the cervical plexus Andrew identified, Barral and Croibier after talking about the cervical plexus in general for treatment, zero in on the Phrenic Nerve. The phrenic nerve? Turns out, it, too comes off C4, is neighbours with the hugely important vagus nerve, and innervates the diaphragm. So what's that got to do with the shoulder?

Turns out as well that the phrenic nerve is really close to the liver - in particular the sensory (as opposed to motor) fibers of the phrenic nerve. Also Glisson's Capsule (fibrous stuff that wraps the liver) is innervated by the phrenic nerve. Indeed, something quite horrible can happen in liver surgery/transplants: the phrenic nerve right branch can get cut - which means half the diaphram can stop contracting, making breathing a challenge.

Enter the Liver Shoulder. So what's this got to do with the shoulder, interesting and all as this seems? Barral and Croibier call the right shoulder "the visceral shoulder."

The authors have a theory that based on the phrenic nerve's spinal segment, its location in the shoulder, and all the action along the pathway connected with viscera, trouble at one part of the nerve could superimpose or transfer sensation to other areas. This kind of effect isn't uncommon. Head's Zones are long standing maps of referred pain from viscera to other areas of the body. In Head's work, liver/gallbladder referred out to neck pain - more what looks like the upper traps area than the shoulder.

More Specific: Periarthritis. Moving into their chapter on the brachial plexus, the authors get into a discussion of right shoulder "periarthritis" in particular. A quick note that periarthritis is a chronic shoulder issue - also known as frozen shoulder. Now in my case i did not have a chronic right shoulder issue - far from it. My right shoulder has been my rock. But i was still interested. They say that of the hundreds (that's quite a bunch) of patients they've looked at with right shoulder periarthritis where the cause wasn't injury, they've found a connection with the liver and gallbladder also being touch sensitive.

A Test: does it hurt less / can you move more when you do this now? What struck me in their discussion is that pain in the right shoulder can come on seemingly from a simple typical movement and get attributed to that movement - when perhaps it's been a visceral issue just appearing. Oh my. They have a test. After checking the right shoulder - they assume a variety of diagnostics - check to see if the liver or gallbladder are touch sensitive.

Now as it turns out, in my case, that area was pretty sensitive - more so on the right than on the left - but heck i was also recovering from some intense DOMS for my first time using a power wheel for roll outs in awhile, so perhaps that was it? None the less, i thought ok, i'll check their evaluation. Starting seated with arm abducted and externally rotated, there are two touch tests for the liver area. I shan't describe them here, but in carrying them out, the question is, can the arm go past the previous range of motion, past the previous pain threshold. Mine went way past. As i told colleagues, i was not a little freaked out.

How Much Liver? The challenge to consider: does this mean that there is some GI related issue screwing with my shoulder?

I don't know. I'm going to do some bloodwork with Bioletics soon just to check on how things are going - i like having a baseline - so will see. But i can say that just massaging the liver/gallbladder area in a way that Kevin Perone once showed me once to help me sleep seemed to have an ongoing, immediate effect in those first key days of getting the inflammation sense of really restricted/painful motion down and range of motion without pain, up. By painful i mean shampooing my head - that much pressure - hurt. Pulling the covers off me in bed hurt. That kind of thing.

What i do know, experientially from this: gentle visceral manipulation around the liver had a remarkable effect.

Update: here's another post courtesy of a find by Randy Hauer that shows a diaphram/shoulder connection - the more direct phrenic end (phrenic innervates diaphragm) to the shoulder.

Related: Barral Institute

Kevin (shown here at 0.22 in doing some one arm pull ups) who demo'd that nice help sleep liver work

Kevin (shown here at 0.22 in doing some one arm pull ups) who demo'd that nice help sleep liver work had studied visceral manipulation

had studied visceral manipulation with the Barral Institute. I'd heard of this in z-health training; experienced kevin's ministrations, but had not put together that the author of this book was the same person as the eponymous institute. More than that, i had not had a direct experience of a test/reassess movement with visceral work and a demonstrable effect.

with the Barral Institute. I'd heard of this in z-health training; experienced kevin's ministrations, but had not put together that the author of this book was the same person as the eponymous institute. More than that, i had not had a direct experience of a test/reassess movement with visceral work and a demonstrable effect.

One of the things we learn in Z-Health is the value of test and reassess. Does the technique make a difference to performance right now (today it might; later today maybe not). For this period, there *seemed* to be a strong correlation between visceral work and shoulder pain reduction rom improvement. Whether the DOMS in my abs were another contributor to phrenic nerve irritation, i dunno, but even if it was, isn't that interesting?

In any case, i am interested to learn more about visceral work.

Back to the Shoulder: Next Part - Enter the Bands

While the visceral work certainly helped - amazingly so - it didn't eliminate the issue with my shoulder.

In the next part of this rehab log, we'll be looking at how bands - in particular light bands - for exploring, loading and testing range of motion work has been helping - a lot and quickly - to get my shoulder back to functioning without pain.

Caveat:

Just a note again, as i said in part one, these posts are just what i've been doing for myself, with myself. They're explorations grounded in practice and what i've learned formally and on my own, but i'm not generalising to say hey, if you want to fix your shoulder, this is what you should do.

As always, if in doubt about a painful experience, check with a qualified medical person - someone who knows athletes and athletic movement and won't tell someone "just don't lift heavy." Once you're cleared for rehab work, check with someone you trust to help formulate that action.

One phrase prior to the next episode that's been resonating with me is dan john's if it's worth doing, do it every day. I think there's a bit of the seminary about Mr John sometimes with expressions like that. Dunno why, but there it is. Taking that "every day" sentiment to heart, however, i have been working my shoulder every day - usually morning and evening. We'll look at how next time, but i'm convinced that lots of pain free movement, lots of the time, is a key healer.

Till next time.

mc

Related Posts

To cut to the chase after the first few days of nothing seeming to calm down what felt like an inflammatory response - that initial owie of restricted motion and soreness - i went looking for some ideas. Since the nervous system is the governor of the body, and the body responds quickly to threats to it (as in the arthrokinetic reflex), it seemed like an idea to look for any nerve responses about the shoulder.

Previously when i was working through the mystery of pain in my left shoulder, UK Osteopath Andrew Bellamy in the comments of that post suggested to keep in mind any mid neck issues (C5-C6) since this is an area where nerves running into the rotator cuff muscles can get squished. When neck nerves get squished they certainly can refer out to the shoulder.

Previously when i was working through the mystery of pain in my left shoulder, UK Osteopath Andrew Bellamy in the comments of that post suggested to keep in mind any mid neck issues (C5-C6) since this is an area where nerves running into the rotator cuff muscles can get squished. When neck nerves get squished they certainly can refer out to the shoulder.To quote Andrew's Comment

The suprapsinatus nerve, ([C4] occ/5/6), which runs through the anterior and middle scalenes, close to the levator scapulae (vital for shoulder shrugging), into the supraspinatus fossa via the notch, under the periosteum (therefore tethered and liable to neural stretching) laterally. It divides in two innervate the supra and infraspinatus muscles. Typically it gives deltod, scapular, biceps and forearm radiating pain when irritated and is a regular mimic of shoulder pathology, especially cuff tear and subacromial impingement.Indeed, here's a wee bit more on the neuropathy of this often troubling site of the suprascapular nerve and the rotator cuff muscles it innervates.

Cervical and Brachial Plexus. Quick aside about nerves: the spine is the origin point for nerves. Nerves send the signals to power anything in our bodies that moves or has signals moving through it. Veins, muscles, tendons, lungs, brain for instance, all have nerves. Most of these nerves are associated with what are known as spinal segments - areas around a given vertebrae. Nerves come off these spinal segments quite often with thicker branches that split into finer strands.

Cervical and Brachial Plexus. Quick aside about nerves: the spine is the origin point for nerves. Nerves send the signals to power anything in our bodies that moves or has signals moving through it. Veins, muscles, tendons, lungs, brain for instance, all have nerves. Most of these nerves are associated with what are known as spinal segments - areas around a given vertebrae. Nerves come off these spinal segments quite often with thicker branches that split into finer strands.These larger nets of nerves are referred to as Plexi. The nerves that connect with our neck, shoulders, arms and hands are part of the Cervical (from C1 to C5) and Brachial Plexus, spinal segments from C5-T1 (T1 is the top of the thoracic spine). It's the shape of these plexi that give the nerve fibers, well, give for being able to stretch, compress, torque and move with the body. Amazing engineering.

From Suprascapular to Phrenic Nerve: the site of pain not the source of pain

It was thinking back to Andrew's comments that made me wonder about a nerve squish troubling my shoulder. There are some good neurodynamic drills that can help release the suprascapular nerve if that's what the impingement is; there are lots of great mobilisations for the head and neck too. These weren't quite doing it for me.

There's a book by Barral and Croibier on the Peripheral Nerves

There's a book by Barral and Croibier on the Peripheral NervesStarting with the area of the cervical plexus Andrew identified, Barral and Croibier after talking about the cervical plexus in general for treatment, zero in on the Phrenic Nerve. The phrenic nerve? Turns out, it, too comes off C4, is neighbours with the hugely important vagus nerve, and innervates the diaphragm. So what's that got to do with the shoulder?

Turns out as well that the phrenic nerve is really close to the liver - in particular the sensory (as opposed to motor) fibers of the phrenic nerve. Also Glisson's Capsule (fibrous stuff that wraps the liver) is innervated by the phrenic nerve. Indeed, something quite horrible can happen in liver surgery/transplants: the phrenic nerve right branch can get cut - which means half the diaphram can stop contracting, making breathing a challenge.

Enter the Liver Shoulder. So what's this got to do with the shoulder, interesting and all as this seems? Barral and Croibier call the right shoulder "the visceral shoulder."

The authors have a theory that based on the phrenic nerve's spinal segment, its location in the shoulder, and all the action along the pathway connected with viscera, trouble at one part of the nerve could superimpose or transfer sensation to other areas. This kind of effect isn't uncommon. Head's Zones are long standing maps of referred pain from viscera to other areas of the body. In Head's work, liver/gallbladder referred out to neck pain - more what looks like the upper traps area than the shoulder.

More Specific: Periarthritis. Moving into their chapter on the brachial plexus, the authors get into a discussion of right shoulder "periarthritis" in particular. A quick note that periarthritis is a chronic shoulder issue - also known as frozen shoulder. Now in my case i did not have a chronic right shoulder issue - far from it. My right shoulder has been my rock. But i was still interested. They say that of the hundreds (that's quite a bunch) of patients they've looked at with right shoulder periarthritis where the cause wasn't injury, they've found a connection with the liver and gallbladder also being touch sensitive.

A Test: does it hurt less / can you move more when you do this now? What struck me in their discussion is that pain in the right shoulder can come on seemingly from a simple typical movement and get attributed to that movement - when perhaps it's been a visceral issue just appearing. Oh my. They have a test. After checking the right shoulder - they assume a variety of diagnostics - check to see if the liver or gallbladder are touch sensitive.

Now as it turns out, in my case, that area was pretty sensitive - more so on the right than on the left - but heck i was also recovering from some intense DOMS for my first time using a power wheel for roll outs in awhile, so perhaps that was it? None the less, i thought ok, i'll check their evaluation. Starting seated with arm abducted and externally rotated, there are two touch tests for the liver area. I shan't describe them here, but in carrying them out, the question is, can the arm go past the previous range of motion, past the previous pain threshold. Mine went way past. As i told colleagues, i was not a little freaked out.

How Much Liver? The challenge to consider: does this mean that there is some GI related issue screwing with my shoulder?

I don't know. I'm going to do some bloodwork with Bioletics soon just to check on how things are going - i like having a baseline - so will see. But i can say that just massaging the liver/gallbladder area in a way that Kevin Perone once showed me once to help me sleep seemed to have an ongoing, immediate effect in those first key days of getting the inflammation sense of really restricted/painful motion down and range of motion without pain, up. By painful i mean shampooing my head - that much pressure - hurt. Pulling the covers off me in bed hurt. That kind of thing.

What i do know, experientially from this: gentle visceral manipulation around the liver had a remarkable effect.

Update: here's another post courtesy of a find by Randy Hauer that shows a diaphram/shoulder connection - the more direct phrenic end (phrenic innervates diaphragm) to the shoulder.

Related: Barral Institute

Kevin (shown here at 0.22 in doing some one arm pull ups) who demo'd that nice help sleep liver work

Kevin (shown here at 0.22 in doing some one arm pull ups) who demo'd that nice help sleep liver workOne of the things we learn in Z-Health is the value of test and reassess. Does the technique make a difference to performance right now (today it might; later today maybe not). For this period, there *seemed* to be a strong correlation between visceral work and shoulder pain reduction rom improvement. Whether the DOMS in my abs were another contributor to phrenic nerve irritation, i dunno, but even if it was, isn't that interesting?

In any case, i am interested to learn more about visceral work.

Back to the Shoulder: Next Part - Enter the Bands

While the visceral work certainly helped - amazingly so - it didn't eliminate the issue with my shoulder.

|

| the micro mini band: excellent for exploratory band rehab |

In the next part of this rehab log, we'll be looking at how bands - in particular light bands - for exploring, loading and testing range of motion work has been helping - a lot and quickly - to get my shoulder back to functioning without pain.

Caveat:

Just a note again, as i said in part one, these posts are just what i've been doing for myself, with myself. They're explorations grounded in practice and what i've learned formally and on my own, but i'm not generalising to say hey, if you want to fix your shoulder, this is what you should do.

As always, if in doubt about a painful experience, check with a qualified medical person - someone who knows athletes and athletic movement and won't tell someone "just don't lift heavy." Once you're cleared for rehab work, check with someone you trust to help formulate that action.

One phrase prior to the next episode that's been resonating with me is dan john's if it's worth doing, do it every day. I think there's a bit of the seminary about Mr John sometimes with expressions like that. Dunno why, but there it is. Taking that "every day" sentiment to heart, however, i have been working my shoulder every day - usually morning and evening. We'll look at how next time, but i'm convinced that lots of pain free movement, lots of the time, is a key healer.

Till next time.

mc

Related Posts

- The Shoulder: Scapula engineering

- Shoulder Engineering: the g/h joint

- Unpacking a mystery that is the shoulder

- Wee interview with Dan John on Pressing Matters

- Interview with Asha Wagner: mastering the beast challenge for women

- Research on Eccentrics for tendon healing

Saturday, March 19, 2011

Got a side stich? Might be time to check your Thoracic Mobility.

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Most folks who've gone for a run - sometimes a bike or horseback ride - have had a side stich, or cramp in the side. Turns out there's a formal name for this experience: exercise related transient abdominal pain (ETAP). Numerous theories have been proposed about the cause of ETAP, from blood flowing into the diaphram (nope) to ligaments among viscera getting shaken (nope), to muscle cramp (amazingly not). These theories are reviewed in an overview of ETAP from 2009 (Muir09). Turns out, the clearest connection for ETAP is thoracic mobility - or the lack of it.

Most folks who've gone for a run - sometimes a bike or horseback ride - have had a side stich, or cramp in the side. Turns out there's a formal name for this experience: exercise related transient abdominal pain (ETAP). Numerous theories have been proposed about the cause of ETAP, from blood flowing into the diaphram (nope) to ligaments among viscera getting shaken (nope), to muscle cramp (amazingly not). These theories are reviewed in an overview of ETAP from 2009 (Muir09). Turns out, the clearest connection for ETAP is thoracic mobility - or the lack of it.

Back in 2004 (Morton04), a letter in the British Journal of Sports Medicine suggested that the stich effect could be induced by palpating vertebrae T8-T12 (lower part of the thoracic spine - pretty much middle of the back and connected to abdominal muscles). Trying to figure out why thoracic issues might be the cause, the authors write

The authors note that in previous work by I.N. Kugelmass (1937), kids who practiced static posture work and breathing exercises eliminated occurrences of stitches. The authors note however that "the relationship between dynamic posture and the experience of ETAP remains a topic for further investigation"

In the interim, the authors suggest that "posture-corrective exercises may be considered a strategy for preventing the pain."

Application

Movements to reduce Stitches - before they come on

Based on these findings, it may be possible to put together a few simple movements and breathing drills to help an athlete reduce stitches by getting the thoracic spine to a happier place.

It might be helpful to note that these kinds of stitches seem to be age related (morton 02): they decrease (1) with age and also, it seems, (2) with increase of training.

It might be helpful to note that these kinds of stitches seem to be age related (morton 02): they decrease (1) with age and also, it seems, (2) with increase of training.

So - thoracic mobilization. There are many ways to help the thoracic spine to move better. Brett Jones and Gray Cook use the thoracic extension work of the Turkish Getup (overview). The familiar RKC Arm Bar also discussed in Jone and Cook's Kalos Sthenos (kettlebelss from the ground up) is another thoracic extension movement that works as a kind of antidote to too much flexion of the thoracic spine (aka going all hunched shoulders), while also helping with shoulder mobilization and strengthening.

Adding In Lateral and Circular Thoracic Work

The thoracic spine however doesn't just move back and forth. It also moves side to side. And really, it moves circularly. The more we practice the full range of motion of these joints, the better we are able to take advantage of that movement.

The anterior/posterior thoracic drills are covered in detail in the R-phase DVD, the Neural Warm Up 1 DVD (Rphase is overviewed here) and in the Quick Start DVD.

Here's Master RKC Geoff Neupert of kettlebell muscle fame demonstrating the above glide AND the RKC arm bar

The lateral (side to side) glides are covered in the R-Phase and Neural Warm Up 1 DVDs, as are the full circle thoracic movements.

Focus focus focus. These simple drills are fabulous for focusing one's attention on *just* the thoracic spine: can we move that part of our body independent of other joints - like the shoulders.

Once we can get the side to side and front to back, getting to circles is inevitable.

I can say with pretty good confidence that when i started doing Z-Health i'd stand side on to a mirror and try to do thoracic glides - it felt like something was moving long before i saw anything moving.

Circles to me seemed impossible. After a month of daily drills with the thoracics though, circles came. I remember RKC Team Leader at the RKC II last year saying how "flexible" my thoracic spine was. Ha, i thought, i guess it is down to perfect reps. It still stuns me.

Breathing/Openning

One of the powerful moves in the progression from R-Phase to I-Phase (I-Phase overview) is the relaxation/breathing drills at the end of the Neural Warmup 2. These are called Front and Side Openers.

These openers combine a bunch of R-phase movements with I-phase load (loading explained in the I-Phase overview): toe pulls, ankle plantar flexion, hip extension, lumbar rotation and extension, thoracic mobility, shoulder flexion, wrist extension and breathing.

The position adds loading to these postures. The focus is yoga-like in that it focuses on relaxing into this posture while working the movement actively.

These are great progressions to help get the thoracic spine to regain its *full* range of motion and control that range of motion. And if the thesis of the various ETAP reviews are correct, for runners, cyclisys and riders with much jolting, these moves will also help reduce incidence of side stitches.

If you suffer from the occaisional stitch, and you try these drills, please let me know how it goes.

Related Posts

Citations

Back in 2004 (Morton04), a letter in the British Journal of Sports Medicine suggested that the stich effect could be induced by palpating vertebrae T8-T12 (lower part of the thoracic spine - pretty much middle of the back and connected to abdominal muscles). Trying to figure out why thoracic issues might be the cause, the authors write

The extent to which the thoracic intercostal nerves may contribute to the experience of ETAP is worthy of further investigation. It seems plausible that, in some cases mechanical compression of the nerve root may refer pain distally, resulting in abdominal pain. Alternatively, irritation of the nerve may sensitise it to stimuli such that the threshold required for activation is lessened. Hence, in this study, palpation after the pain had been relieved may have allowed tissues innervated by the intercostal nerves, such as the abdominal musculature or parietal peritoneum, to recreate sensations of pain.More recently in 2010, the issue of a possible spinal connection with ETAP resurfaced (Morton10). Two factors were considered: posture and body type. No correlation was found between body type (somatotype like mesomorph, ectomorph, etc). Where there was a connection, again, seems to be with the throracic spine. Indeed, the authors found what seems to be a correlation between incidents of reported ETAP and measures of kyphosis. As they note:

So what's the Fix? Breath deep and Move the SpineFrom a mechanistic viewpoint, increased curvature of the thoracic spine could influence the experience of ETAP either functionally and/or neurally. Functionally, kyphosis could affect rib cage mechanics, as asserted by Kugelmass,10 conceivably placing atypical stresses upon other abdominal structures. Kugelmass made this assertion to support his theory that ETAP was caused by compromised diaphragm function, which has since been convincingly discredited.[1], [5] and [6] From a neural perspective, the abdominal region is innervated by spinal nerves arising from thoracic vertebrae T712.19 Notably, abdominal pain similar in nature to ETAP has been evoked by lesions and compression of these spinal nerves.[12], [20] and [21] Further, we have been able to reproduce symptoms of ETAP by palpating sites adjacent to T7 through T12.4

The authors note that in previous work by I.N. Kugelmass (1937), kids who practiced static posture work and breathing exercises eliminated occurrences of stitches. The authors note however that "the relationship between dynamic posture and the experience of ETAP remains a topic for further investigation"

In the interim, the authors suggest that "posture-corrective exercises may be considered a strategy for preventing the pain."

Application

Movements to reduce Stitches - before they come on

Based on these findings, it may be possible to put together a few simple movements and breathing drills to help an athlete reduce stitches by getting the thoracic spine to a happier place.

It might be helpful to note that these kinds of stitches seem to be age related (morton 02): they decrease (1) with age and also, it seems, (2) with increase of training.

It might be helpful to note that these kinds of stitches seem to be age related (morton 02): they decrease (1) with age and also, it seems, (2) with increase of training. So - thoracic mobilization. There are many ways to help the thoracic spine to move better. Brett Jones and Gray Cook use the thoracic extension work of the Turkish Getup (overview). The familiar RKC Arm Bar also discussed in Jone and Cook's Kalos Sthenos (kettlebelss from the ground up) is another thoracic extension movement that works as a kind of antidote to too much flexion of the thoracic spine (aka going all hunched shoulders), while also helping with shoulder mobilization and strengthening.

Adding In Lateral and Circular Thoracic Work

The thoracic spine however doesn't just move back and forth. It also moves side to side. And really, it moves circularly. The more we practice the full range of motion of these joints, the better we are able to take advantage of that movement.

| ||

| a seated variant of the thoracic posterior glide, from the Quick Start DVD |

The lateral (side to side) glides are covered in the R-Phase and Neural Warm Up 1 DVDs, as are the full circle thoracic movements.

Focus focus focus. These simple drills are fabulous for focusing one's attention on *just* the thoracic spine: can we move that part of our body independent of other joints - like the shoulders.

|

| Lateral Thoracic Glides |

I can say with pretty good confidence that when i started doing Z-Health i'd stand side on to a mirror and try to do thoracic glides - it felt like something was moving long before i saw anything moving.

Circles to me seemed impossible. After a month of daily drills with the thoracics though, circles came. I remember RKC Team Leader at the RKC II last year saying how "flexible" my thoracic spine was. Ha, i thought, i guess it is down to perfect reps. It still stuns me.

| |

| R-Phase Neural Warm Up |

Breathing/Openning

One of the powerful moves in the progression from R-Phase to I-Phase (I-Phase overview) is the relaxation/breathing drills at the end of the Neural Warmup 2. These are called Front and Side Openers.

|

| I-Phase NWU2 |

The position adds loading to these postures. The focus is yoga-like in that it focuses on relaxing into this posture while working the movement actively.

These are great progressions to help get the thoracic spine to regain its *full* range of motion and control that range of motion. And if the thesis of the various ETAP reviews are correct, for runners, cyclisys and riders with much jolting, these moves will also help reduce incidence of side stitches.

If you suffer from the occaisional stitch, and you try these drills, please let me know how it goes.

Related Posts

Citations

Morton, D., Callister, R. (2010). Influence of posture and body type on the experience of exercise-related transient abdominal pain Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 13 (5), 485-488 DOI: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.10.487Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Morton, D. (2004). Runner's stitch and the thoracic spine British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38 (2), 240-240 DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.009308

MORTON, D., CALLISTER, R. (2002). Factors influencing exercise-related transient abdominal pain Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 34 (5), 745-749 DOI: 10.1097/00005768-200205000-00003

Muir B (2009). Exercise related transient abdominal pain: a case report and review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 53 (4), 251-60 PMID: 20037690

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

shoulder rehab - a very (very) active approach - a journey log, pt 1

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Shoulder injuries suck. Getting one on one side after months of rehabbing the other side sucks even more. One may also imagine a revision to Oscar Wilde - To injure one shoulder may be regraded as a misfortune; to injure both looks like carelessness. And perhaps it was. So, can the knowledge gained in rehabbing one shoulder over months be applied to the other to rehab it in weeks?

The following posts are a few notes on my journey to take lessons learned about the shoulder from an injury last spring - 10 months ago'ish now - and applying them to my right shoulder. The result seems to be a surprisingly accelerated recovery occurring on the right.

I offer these notes not as a "here's what to do if this sounds like you" but just some observations on what i've found useful in my own rehab.

Cut to the Chase: main rehab strategy

If you want to cut to the chase, the biggest therapeutic work right now seems to be loaded mobility work exploring the edge of range of motion limits - where those limits are pretty clearly communicated by an edge of pain.

I am fascinated by how quickly this work into the edge of the limit seems to be having rapid restorative effects. I'll discuss the approach in more detail as we move on.

Background

Last spring not long after getting back from the amazing RKC II weekend in San Jose, Feb 2010, i somehow woke up one morning and my left shoulder was in significant pain. Reaching behind me to put on my coat was the most awful experience.

6 weeks or so after the initial pain, went to see the doc as things seemed to be getting worse. The doc suggested "painful arc syndrome" which meant rotator cuff issue and take some NSAIDs to bring down the inflammation. As i've written about before, the drugs really did bring down the pain, but my pressing goals got shot. I learned that a sore left side can screw up a functioning right side: i just could not press with as much vigour without inducing a pain response on the left. Yuck.

Where did this come from? What was it?

I learned a lot about repetitive strain injuries, and about resarch into eccentrics for healing these kinds of issues. I learned about the differences between itis or osis, and why most up on current practice medicos and resaerchers just talk about opathies instead. Eccentric training was not doing it for me. Physio not so much. Secrets of the shoulder - awseome stuff but wasn't giving me a breakthrough.

Mid October *finally* got some work done with me on finding a path into the shoulder; turned out, no not really a shoulder thing per se (the source of pain may not be the site of pain, i seem to recall hearing some where), more a biceps thing - got a super path to start rebuilding there. If you'd like to explore the detail of that analysis and the specific rehab for what was happening, that story is linked here.

More Recently

Finally, a little more than a month ago, as i wrote recently, i got back into my double KB work via Return of the Kettlebell. It was hard to deal with how much ground i'd lost, where i was doing three ladders rather than five; max on left was a 12 for reps not the 16, but there were also some definite wins. It only took about a week of effort to be able to press the 16 on the left again for singles; two weeks to get three reps. That's a far cry from doing three - four sets of five ladders - or 15 reps - but there was progress. All good. I was starting to snatch again - with just the 12 on the left, but it's a start.

And then it happened: on heavy day of the RTK pressing cycle, third ladder in with the 16 on the right, and something felt really not good. As far as i could tell, my form had been ok; i didn't feel anything go, but that was it. And there was pain.

My immediate response was to try some neural dynamic/ mechanic work to get at the nerves that innervate the shoulder and the biceps. The shoulder work was fine; the supraspinatus work, not so much; musculo-cutaneous (biceps nerve) not great.

Emotional Experience More debilitating than Injury?

Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of an injury is the emotional game: here i was just a month off one injury that happened to unhinge my passion - pressing a 24 - and now my *best* shoulder was hit. It can be challenging to find a way to stay up with one's practice.

Suffice it to say i think that i did not want this right shoulder to unhinge me again. But what to do? Just lifting the covers off me in the morning was let's say a more sharply wakeful experience than an alarm; trying to reach my head to wash my hair, little own put any pressure on my head was not a good thing either. Big back away signals.

Strategy for come back

So what to do? Use what ya know; test it; refine it.

Over the past year i'd been training for my zhealth master trainer designation (the plaque just came the other day. cool. new wall gets started). Part of that training is a whole lot of anatomy, with a major focus on nerves and spinal sections related to joint movement. Cool stuff to get that something happening in one's neck is manifest in one's fingers, and that working with the source at the neck can affect the peripheral manifestation.

There are a lot of expressions regarding integrity of practice: does one walk the walk or just talk the talk; does one eat one's own dog food - i.e. the products that one produces for a particular task.

My own injury has given me a chance to explore the techniques i know and the skills i've developed for investigating new (to me) approaches.

Coming Up

So here's a bit of a path i'll discuss in the upcoming posts:

In the coming discussion, i will make no claims that what i've done, what i'm doing in my rehab is great for everyone - or for that matter anyone else. What i will say is that the protocol i've learned with my colleagues going through the Master Trainer progressions is test and reassess everything. We have a lot of tools; they're not total; i've learned a bunch outside that program as well, but the thing i've found has been working for me is this simple concept of test and reassess. Try anything: just have a way to evaluate if it's having an effect, and if that effect is positive.

Principled Hack. Something else i've learned in the process is that there is great value - at least for myself - in having learned something of our fundamental mechanics, but almost even more so, of our fundamental wiring. Knowing something about our inner organisation has given me a more principled way to approach at least to picking a starting point: i think i have a better model about why i might see an effect or not.

At times i'm still stunned by these connections: working with a young gal with arthritis with really high pain and limited range of motion. We tried a drill to work the nerves involved firing the painful muscles; nothing. So we then engaged that spinal segment of where the nerve starts along with the drill, and wow, the range of motion went up; pain went down. I get a little verklempt every time i think of that. It's not an isolated example. What it means tho, is that by having a better model of us - how muscles, joints, nerves, guts connect, that helps me apply the tools i have better. Makes sense, doesn't it? Sounds obvious, but initially i didn't get that as clearly as i have of late able to add these models to practice.

In computing sometimes one might refer to a hack in code as a fast fix for a problem. Hacks are great. They are like the coding equivalent of duck tape. And about as robust. A principled hack will be something more robust, but no one is claiming that it's the absolute optimal solution to the problem. I guess i feel like i'm a bit further down the road where my approach to what i do is more principled. In many cases it's exactly the same, but perhaps more refined and efficient. Hence this test on myself.

Motivation to Learn: Load is a Great Teacher. One other thing i've found with respect to learning is that there is one thing that will accelerate learning: if one has to teach the material. Anyone who's had to teach at any level will know what it's like to be asked to teach a new course or fill in for a colleague. One has to get up to speed fast.

I'm finding that something else that drives one to learn, to develop new solutions is an injury. Perhaps with my left shoulder learning, the folks i've had the pleasure to work with on their pain/performance, and the fact that i have some great colleagues who are there to draw on for their experience, i have greater confidence to say i'm going to have a go at this myself; i'm going to treat myself as the client and see what i can do.

Progress. So far, i've been surprised (and occaisionally stunned) by the seeming rapidity of the results. It's too early to sign off on this injury: i'm in the middle of rehabbing, and i tell myself well maybe this is a way less intense injury than the left side was etc etc, but so what? i'll take it: it seems to be coming together much faster. I could lift the covers off me this morning without stiffling a yelp, and could almost put full pressure on my head when shampooing. Two days ago, i could not.

Gonzo Healing.

So why talk about this? I learned last night that what i had thought was gonzo journalism - no holds barred, deep risky reporting - was not right at all. Gonzo, it turns out, is more the destruction of the idea of journalistic objectivity; of being willing to put oneself explicitly in the story, rather than try to pretend one is an objective tape recorder.

So let's call this gonzo healing or healing practice: i'm in the middle of a process now; it may all end in tears; it may be great. Either way, it may be interesting to reflect on the process as it's happening.

Thanks for joining the investigation.

Other Posts in this Series

Related Stories

Shoulder injuries suck. Getting one on one side after months of rehabbing the other side sucks even more. One may also imagine a revision to Oscar Wilde - To injure one shoulder may be regraded as a misfortune; to injure both looks like carelessness. And perhaps it was. So, can the knowledge gained in rehabbing one shoulder over months be applied to the other to rehab it in weeks?

The following posts are a few notes on my journey to take lessons learned about the shoulder from an injury last spring - 10 months ago'ish now - and applying them to my right shoulder. The result seems to be a surprisingly accelerated recovery occurring on the right.

I offer these notes not as a "here's what to do if this sounds like you" but just some observations on what i've found useful in my own rehab.

Cut to the Chase: main rehab strategy

If you want to cut to the chase, the biggest therapeutic work right now seems to be loaded mobility work exploring the edge of range of motion limits - where those limits are pretty clearly communicated by an edge of pain.

I am fascinated by how quickly this work into the edge of the limit seems to be having rapid restorative effects. I'll discuss the approach in more detail as we move on.

Background

|

| Pondering rehab at the office. see the RKC II cert? |

6 weeks or so after the initial pain, went to see the doc as things seemed to be getting worse. The doc suggested "painful arc syndrome" which meant rotator cuff issue and take some NSAIDs to bring down the inflammation. As i've written about before, the drugs really did bring down the pain, but my pressing goals got shot. I learned that a sore left side can screw up a functioning right side: i just could not press with as much vigour without inducing a pain response on the left. Yuck.

Where did this come from? What was it?

I learned a lot about repetitive strain injuries, and about resarch into eccentrics for healing these kinds of issues. I learned about the differences between itis or osis, and why most up on current practice medicos and resaerchers just talk about opathies instead. Eccentric training was not doing it for me. Physio not so much. Secrets of the shoulder - awseome stuff but wasn't giving me a breakthrough.

Mid October *finally* got some work done with me on finding a path into the shoulder; turned out, no not really a shoulder thing per se (the source of pain may not be the site of pain, i seem to recall hearing some where), more a biceps thing - got a super path to start rebuilding there. If you'd like to explore the detail of that analysis and the specific rehab for what was happening, that story is linked here.

More Recently

Finally, a little more than a month ago, as i wrote recently, i got back into my double KB work via Return of the Kettlebell. It was hard to deal with how much ground i'd lost, where i was doing three ladders rather than five; max on left was a 12 for reps not the 16, but there were also some definite wins. It only took about a week of effort to be able to press the 16 on the left again for singles; two weeks to get three reps. That's a far cry from doing three - four sets of five ladders - or 15 reps - but there was progress. All good. I was starting to snatch again - with just the 12 on the left, but it's a start.

And then it happened: on heavy day of the RTK pressing cycle, third ladder in with the 16 on the right, and something felt really not good. As far as i could tell, my form had been ok; i didn't feel anything go, but that was it. And there was pain.

My immediate response was to try some neural dynamic/ mechanic work to get at the nerves that innervate the shoulder and the biceps. The shoulder work was fine; the supraspinatus work, not so much; musculo-cutaneous (biceps nerve) not great.

Emotional Experience More debilitating than Injury?

|

| office kb pile |

Suffice it to say i think that i did not want this right shoulder to unhinge me again. But what to do? Just lifting the covers off me in the morning was let's say a more sharply wakeful experience than an alarm; trying to reach my head to wash my hair, little own put any pressure on my head was not a good thing either. Big back away signals.

Strategy for come back

So what to do? Use what ya know; test it; refine it.

Over the past year i'd been training for my zhealth master trainer designation (the plaque just came the other day. cool. new wall gets started). Part of that training is a whole lot of anatomy, with a major focus on nerves and spinal sections related to joint movement. Cool stuff to get that something happening in one's neck is manifest in one's fingers, and that working with the source at the neck can affect the peripheral manifestation.

There are a lot of expressions regarding integrity of practice: does one walk the walk or just talk the talk; does one eat one's own dog food - i.e. the products that one produces for a particular task.

My own injury has given me a chance to explore the techniques i know and the skills i've developed for investigating new (to me) approaches.

Coming Up

So here's a bit of a path i'll discuss in the upcoming posts:

- looking at the new injury with the findings of the previous one: wrist extensors, brachioradialis and the tendon on the long head of the biceps

- mapping out some key nerve-joint-breath connexions towards relief.

- looking at the right shoulder/liver connection

- exploring end range of motion, terminal flicking and isometrics

- tuning the lat; locking the pelvis

- the pleasures of rubber bands, anytime, anywhere: load to learn.

- the importance of time: time to make an assessment and test and readjust

"I am not young enough to know everything"

attributed to Oscar Wilde

In the coming discussion, i will make no claims that what i've done, what i'm doing in my rehab is great for everyone - or for that matter anyone else. What i will say is that the protocol i've learned with my colleagues going through the Master Trainer progressions is test and reassess everything. We have a lot of tools; they're not total; i've learned a bunch outside that program as well, but the thing i've found has been working for me is this simple concept of test and reassess. Try anything: just have a way to evaluate if it's having an effect, and if that effect is positive.

Principled Hack. Something else i've learned in the process is that there is great value - at least for myself - in having learned something of our fundamental mechanics, but almost even more so, of our fundamental wiring. Knowing something about our inner organisation has given me a more principled way to approach at least to picking a starting point: i think i have a better model about why i might see an effect or not.

At times i'm still stunned by these connections: working with a young gal with arthritis with really high pain and limited range of motion. We tried a drill to work the nerves involved firing the painful muscles; nothing. So we then engaged that spinal segment of where the nerve starts along with the drill, and wow, the range of motion went up; pain went down. I get a little verklempt every time i think of that. It's not an isolated example. What it means tho, is that by having a better model of us - how muscles, joints, nerves, guts connect, that helps me apply the tools i have better. Makes sense, doesn't it? Sounds obvious, but initially i didn't get that as clearly as i have of late able to add these models to practice.

In computing sometimes one might refer to a hack in code as a fast fix for a problem. Hacks are great. They are like the coding equivalent of duck tape. And about as robust. A principled hack will be something more robust, but no one is claiming that it's the absolute optimal solution to the problem. I guess i feel like i'm a bit further down the road where my approach to what i do is more principled. In many cases it's exactly the same, but perhaps more refined and efficient. Hence this test on myself.

Motivation to Learn: Load is a Great Teacher. One other thing i've found with respect to learning is that there is one thing that will accelerate learning: if one has to teach the material. Anyone who's had to teach at any level will know what it's like to be asked to teach a new course or fill in for a colleague. One has to get up to speed fast.

I'm finding that something else that drives one to learn, to develop new solutions is an injury. Perhaps with my left shoulder learning, the folks i've had the pleasure to work with on their pain/performance, and the fact that i have some great colleagues who are there to draw on for their experience, i have greater confidence to say i'm going to have a go at this myself; i'm going to treat myself as the client and see what i can do.

Progress. So far, i've been surprised (and occaisionally stunned) by the seeming rapidity of the results. It's too early to sign off on this injury: i'm in the middle of rehabbing, and i tell myself well maybe this is a way less intense injury than the left side was etc etc, but so what? i'll take it: it seems to be coming together much faster. I could lift the covers off me this morning without stiffling a yelp, and could almost put full pressure on my head when shampooing. Two days ago, i could not.

Gonzo Healing.

So why talk about this? I learned last night that what i had thought was gonzo journalism - no holds barred, deep risky reporting - was not right at all. Gonzo, it turns out, is more the destruction of the idea of journalistic objectivity; of being willing to put oneself explicitly in the story, rather than try to pretend one is an objective tape recorder.

So let's call this gonzo healing or healing practice: i'm in the middle of a process now; it may all end in tears; it may be great. Either way, it may be interesting to reflect on the process as it's happening.

Thanks for joining the investigation.

Other Posts in this Series

- PART II of this shoulder journal: liver/shoulder connection

- Part III: skin/fascia movement and shoulder rehab.

Related Stories

- The Shoulder: Part I - scapula world

- The shoulder: Part II - g/h joint

- tendon - opathies and eccentric contractions for repair

- The Biceps - not the shoulder - after all.

- Fish oil and being anti-inflammatory.

- One less rep: the differnece between injury and success?

- What's a movement assessment?

- Pressing Matters: a wee chat with Dan John.

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Different Speeds have Different Meanings in our Bodies' Performance in Pain

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Every little thing in the complex systems that are us seems to impact every other thing - or at least a whole lot of other things. Take speed. Have you ever tried to do a familiar movement either really fast or really slow? Say whipping an egg in a bowl, making a shoulder circle, lifting a knee up and down. Speed changes performance, doesn't it? Something else we've seen change performance is pain: pain will change even what muscles get recruited,when, performing an action (Cools; Ferguson). Recent research has put pain and speed together to see what happens in normal walking mechanics.