Showing posts with label zhealth. Show all posts

Showing posts with label zhealth. Show all posts

Saturday, August 14, 2010

A Model of an Athlete, of Athletecisim: z-health's 9s - also a model of coaching

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Here's a question that seems to be poking me on from the earlier "do we enjoy all our workouts/practices/training sessions?" And it's: What is our model of performance? what are the qualities to which we aspire in terms of living what i'm increasingly seeing as "embodied" lives - where we get that we're not just brains with bodies, but that our bodies are life enhancing? Before answering this, one might wonder why do we need a model? Why not just you know, keep moving? Eat well, rest well, move well.

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People demonstrates why

demonstrates why having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great  attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First

and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First  is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

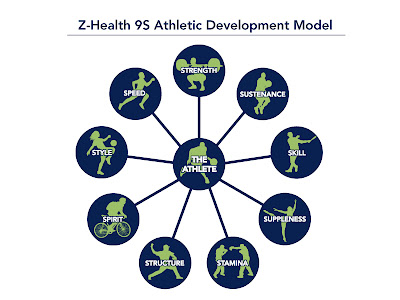

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated , and as Gladwell notes in Outliers

, and as Gladwell notes in Outliers , putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

, putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

|

| The Z-Health 9S model of the Athlete |

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

9S,

coach,

principles,

z-health,

zhealth

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Head Shift: Why not look for More Time to Move rather than as Little as Possible?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Maybe we should seek to move more rather than the least amount possible in a week. Maybe that's a much better place to be. Let's consider why that might help us out in so many parts of our lives, and the research that supports it. This proposal is set against popular approaches to fitness. Lots of folks celebrate ways for us to "take less time" to work out. After all, there's more to life than being in the gym. For sure. And i'm all for efficiency and elegance in all things. A stupid workout may just be a stupid workout: when you take an hour, make it a beautiful hour.

Maybe we should seek to move more rather than the least amount possible in a week. Maybe that's a much better place to be. Let's consider why that might help us out in so many parts of our lives, and the research that supports it. This proposal is set against popular approaches to fitness. Lots of folks celebrate ways for us to "take less time" to work out. After all, there's more to life than being in the gym. For sure. And i'm all for efficiency and elegance in all things. A stupid workout may just be a stupid workout: when you take an hour, make it a beautiful hour.

But what i've been thinking about really is that we are so wrong wrong wrong when we take what i'm increasingly seeing as the "brains with bodies" approach to movement: we seek to find the smallest slice of time during the week for our movement, like that's the least important part of our day, a chore to be got rid of. As exciting and necessary as flossing one's teeth.

But we are not just brains with bodies that like the neighbour's dog we are burdened with having to take for a walk once a day when they're on holiday. How many of us make excuses like we don't have time to move - to walk, to run, to pick stuff up and put it down, to play a game? Our bodies are often constructed culturally as burdens rather than collaborators in our life's work and pleasure.

But we are not just brains with bodies that like the neighbour's dog we are burdened with having to take for a walk once a day when they're on holiday. How many of us make excuses like we don't have time to move - to walk, to run, to pick stuff up and put it down, to play a game? Our bodies are often constructed culturally as burdens rather than collaborators in our life's work and pleasure.

And sure those "workouts in 6 mins" or 20 mins or whatever are all trying to get folks "at least doing something" - but again, maybe that's just the wrong message to be sending. In whose interests is it for us to be just well enough to keep going to work and not costing a health plan or workers comp for down time?

Movement is Smart(er) - no really.

As i do more work on movement and the way we are wired, it's increasingly clear that the opposite is true: we owe it to ourselves, cognitively and physically to find any time we can to move; in as many ways and at as many speeds as we can. When we don't use parts of our brains, the circuits re-route to what we do use. This is verified in the past 20 years of neurology.

We are use it or lose it systems. Our bodies adapt all the time. And this is systemic. What we don't use - like bone mineral density - gets taken away. Seriously, no joke. Likewise when we don't move joints in their ROM they start to osify or go arthritic in the unused portions.

We are use it or lose it systems. Our bodies adapt all the time. And this is systemic. What we don't use - like bone mineral density - gets taken away. Seriously, no joke. Likewise when we don't move joints in their ROM they start to osify or go arthritic in the unused portions.

The above use it or lose it paradigm may still be read as we are enslaved by our bodies and so we must find the shortest most optimal path to do the least amount of work to get the most benefit. And that, too, seems to be a way way wrong and unhealthy and unhelpful life attitude. Phooey, i say.

Consider this: life may be more fun and brilliant if we see our bodies as part of who we are.

Skilled movement practice, for instance, lights up our brains in MRIs. There is increasing evidence likewise that movement enhances intellectual performance. Studies done with kids show especially the earlier "exercise" starts, the greater the intellectual benefits [2007, 2009a, 2009b ]. But at the other end of the scale, movement has been seen to help elderly at risk of observed cognitive decline, recover function, too [2010a]. Likewise, general memory function endurance is assisted by exercise/movement, and enhances brain plasticity [2010].

Skilled movement practice, for instance, lights up our brains in MRIs. There is increasing evidence likewise that movement enhances intellectual performance. Studies done with kids show especially the earlier "exercise" starts, the greater the intellectual benefits [2007, 2009a, 2009b ]. But at the other end of the scale, movement has been seen to help elderly at risk of observed cognitive decline, recover function, too [2010a]. Likewise, general memory function endurance is assisted by exercise/movement, and enhances brain plasticity [2010].

Indeed, the studies have become so rife connecting movement with intelligence that there's even a popular press book out right now called Spark: How exercise will improve the performance of your brain . The book summarizes a lot the findings and puts together cognitve enhancing exercise programs.

. The book summarizes a lot the findings and puts together cognitve enhancing exercise programs.

Inert = Loss of Comepetetive Edge

It seems pretty clear now that for those of us who are "knowledge workers" we are also actually doing ourselves a competitive disservice by staying as innert as possible, moving as little as possible - whatever that means. But again - that may sound like a threat, and the body/burden thing raises its head. We imagine scenes from Gattica and forced treadmill running and heart rate monitoring.

Moving, though, if we take it that that's what we're designed to do, is something we can do everywhere at anytime - or at least we can so imagine. In the work environment, there are desks that let us stand or sit; working at whiteboards that let us stand and walk around. These facilitate movement. And no i'm not a fan of treadmill desks. They may burn calories but can play havok with gait, visual and vestibular systems - juries way out and tending to no. Lord, if we got beyond the "calorie burn" as the only reason to move it move it, we wouldn't have to worry about desks.

Example of Action Work. A colleague of mine has only a standing desk in his office, and otherwise has many rehab balls (usually pretty squishy) for lounging. No chairs. He gets up in the middle of meetings and paces. He's also a dancer, not just a field leading computer scientist. It's great. That's movement. He bikes to work and his main moving gig is his folk dancing. That's healthy. Multiplanar movement. Awesome. AND HE ENJOYS IT - he loves to dance. It's part of his life; not something that he must do. He actually shapes his "real job" schedule around his weekly dance classes. And boy is he smart. Sharp sharp, that one. Connection? As we've seen, research suggests it helps.

I wrote about awhile ago how pick up games of five a side football were about the best blend of strength workouts one could get and got lots of comments from colleagues about how much they enjoy that kind of thing "when it happens" - maybe we need to make it happen.

Perhaps we need to fall in love with being in our bodies? Want to take them out on dates. Play dates. Learn to enjoy treating them/ourselves to what turns on the happy hormones and helps us feel better. Which is another cool thing: the more we move, the better we tend to feel overall - again, cognitively as well as in terms of general wellbeing. Stress gets blown off better; food gets processed better. We feel better about ourselves

Five+ Hours a week - to be happy with ones body?

John Berardi of Precision Nutrition has worked with hundreds (or thousands now) of clients for years. His take away has reinforced that folks who move it a minimum of five hours a week seems to correlate most strongly with greatest self-satisfaction with body image. My sense is increasingly that five+ hours a week correlates with more kinds of wellbeing than just body comp.

Now some of us can't imagine five whole hours a week just getting our body to move. We want to do the intervals or the whatever that are at most 3 sessions per week for 20 mins. And heck, i've written about working out for just 6 mins a week that has equivalent effect as hours of cardio, or elsewhere 660secs a week to show a considerable difference for overweight geeks. The theme is always "it only takes this teeny weeny amount to have an effect" - so why do more, right? Like we're off the hook then. I mean if all we need is 6 super intense minutes, the rest be dammed. We can get back to the screen.

What Systems Are Measured in Minimal Movement Studies?

But what's the effect? cardio vascular well being. Heavens knows that's important. But what about the rest of us? The respiratory and cardiovascular systems - the two most often discussed in health as part of "aeorbic fitness" - are only two of eleven physiological systems in the body. That leaves nine more to go. Consider the skin, skeleton, muscles, nervous system, hormones, lymph, sex, waste, digestion. What do they need? Turns out movement is pretty good for all of them.

To give one example, breathing is a big pump for lymph circulation and flushing. Exercise helps work breathing, so that has an impact on immune function. Movement, especially loaded work and c/v work, we know helps fascilitate nutrient uptake, and hormonal balance like insulin sensitivity. Stop/start movement like socer or weight lifting is great for our use-it-or-lose-em bones. Indeed we know that joints literally start to seize up from lack of movement in full range of motion, or develop pain conditions like RSI from overuse of one movement direction unbalanced by the others in that joint/muscle combination. It's amazing that we don't all keel over with *only* 20mins, 3 times a week of some kind of activity

Being Embodied Can be Fun

Brad Pilon made an observation on facebook lately

Also before the strength and suppleness course, we played frisbee at the end of the day. An hour of catch and a game of Ultimate each night and you've bagged your 5 hours without even thinking about it. The challenge is now to implement something similar back in Normal World.

Changing Perspective; New Discoveries.

Einstein is attributed with saying something to the effect that we can't solve our problems with the tools that created them. Easy for Mr. Paradigm Shifter I invented Relativity and topped Newtonian Physics guy to say, perhaps, but it's a salutory thought.

In this case, the fast food head space that wants what it wants now and for the minimal effort in order to go do something else - to not pay attention to what we eat; to not pay attention to how we move - is the problem, and trying to find a solution for our emotional (stress), physical and nutrional whiles with the least effort/time possible is entirely the wrong paradigm.

Maybe the paradigm shift is - what do i need to change to move the MOST i can during the day, the week, now? Related might be: What do i need to do to get the most pleasure from the best food today, to be present to being here as much as possible, to have the best rest tonight to concentrate the most i can on what i do now and later?

We're fully integrated, physical creatures, though our world is increasingly designed to shape us as brains with bodies. Abandoning that belief and moving towards the Movement Light as much rather than as little as possible feels and performs, it seems, a whole lot better - across all the rest of what we do, too, don't you think?.

Refs

But what i've been thinking about really is that we are so wrong wrong wrong when we take what i'm increasingly seeing as the "brains with bodies" approach to movement: we seek to find the smallest slice of time during the week for our movement, like that's the least important part of our day, a chore to be got rid of. As exciting and necessary as flossing one's teeth.

And sure those "workouts in 6 mins" or 20 mins or whatever are all trying to get folks "at least doing something" - but again, maybe that's just the wrong message to be sending. In whose interests is it for us to be just well enough to keep going to work and not costing a health plan or workers comp for down time?

Movement is Smart(er) - no really.

As i do more work on movement and the way we are wired, it's increasingly clear that the opposite is true: we owe it to ourselves, cognitively and physically to find any time we can to move; in as many ways and at as many speeds as we can. When we don't use parts of our brains, the circuits re-route to what we do use. This is verified in the past 20 years of neurology.

We are use it or lose it systems. Our bodies adapt all the time. And this is systemic. What we don't use - like bone mineral density - gets taken away. Seriously, no joke. Likewise when we don't move joints in their ROM they start to osify or go arthritic in the unused portions.

We are use it or lose it systems. Our bodies adapt all the time. And this is systemic. What we don't use - like bone mineral density - gets taken away. Seriously, no joke. Likewise when we don't move joints in their ROM they start to osify or go arthritic in the unused portions.The above use it or lose it paradigm may still be read as we are enslaved by our bodies and so we must find the shortest most optimal path to do the least amount of work to get the most benefit. And that, too, seems to be a way way wrong and unhealthy and unhelpful life attitude. Phooey, i say.

Consider this: life may be more fun and brilliant if we see our bodies as part of who we are.

Skilled movement practice, for instance, lights up our brains in MRIs. There is increasing evidence likewise that movement enhances intellectual performance. Studies done with kids show especially the earlier "exercise" starts, the greater the intellectual benefits [2007, 2009a, 2009b ]. But at the other end of the scale, movement has been seen to help elderly at risk of observed cognitive decline, recover function, too [2010a]. Likewise, general memory function endurance is assisted by exercise/movement, and enhances brain plasticity [2010].

Skilled movement practice, for instance, lights up our brains in MRIs. There is increasing evidence likewise that movement enhances intellectual performance. Studies done with kids show especially the earlier "exercise" starts, the greater the intellectual benefits [2007, 2009a, 2009b ]. But at the other end of the scale, movement has been seen to help elderly at risk of observed cognitive decline, recover function, too [2010a]. Likewise, general memory function endurance is assisted by exercise/movement, and enhances brain plasticity [2010].Indeed, the studies have become so rife connecting movement with intelligence that there's even a popular press book out right now called Spark: How exercise will improve the performance of your brain

Inert = Loss of Comepetetive Edge

It seems pretty clear now that for those of us who are "knowledge workers" we are also actually doing ourselves a competitive disservice by staying as innert as possible, moving as little as possible - whatever that means. But again - that may sound like a threat, and the body/burden thing raises its head. We imagine scenes from Gattica and forced treadmill running and heart rate monitoring.

Moving, though, if we take it that that's what we're designed to do, is something we can do everywhere at anytime - or at least we can so imagine. In the work environment, there are desks that let us stand or sit; working at whiteboards that let us stand and walk around. These facilitate movement. And no i'm not a fan of treadmill desks. They may burn calories but can play havok with gait, visual and vestibular systems - juries way out and tending to no. Lord, if we got beyond the "calorie burn" as the only reason to move it move it, we wouldn't have to worry about desks.

Example of Action Work. A colleague of mine has only a standing desk in his office, and otherwise has many rehab balls (usually pretty squishy) for lounging. No chairs. He gets up in the middle of meetings and paces. He's also a dancer, not just a field leading computer scientist. It's great. That's movement. He bikes to work and his main moving gig is his folk dancing. That's healthy. Multiplanar movement. Awesome. AND HE ENJOYS IT - he loves to dance. It's part of his life; not something that he must do. He actually shapes his "real job" schedule around his weekly dance classes. And boy is he smart. Sharp sharp, that one. Connection? As we've seen, research suggests it helps.

I wrote about awhile ago how pick up games of five a side football were about the best blend of strength workouts one could get and got lots of comments from colleagues about how much they enjoy that kind of thing "when it happens" - maybe we need to make it happen.

Perhaps we need to fall in love with being in our bodies? Want to take them out on dates. Play dates. Learn to enjoy treating them/ourselves to what turns on the happy hormones and helps us feel better. Which is another cool thing: the more we move, the better we tend to feel overall - again, cognitively as well as in terms of general wellbeing. Stress gets blown off better; food gets processed better. We feel better about ourselves

Five+ Hours a week - to be happy with ones body?

John Berardi of Precision Nutrition has worked with hundreds (or thousands now) of clients for years. His take away has reinforced that folks who move it a minimum of five hours a week seems to correlate most strongly with greatest self-satisfaction with body image. My sense is increasingly that five+ hours a week correlates with more kinds of wellbeing than just body comp.

Now some of us can't imagine five whole hours a week just getting our body to move. We want to do the intervals or the whatever that are at most 3 sessions per week for 20 mins. And heck, i've written about working out for just 6 mins a week that has equivalent effect as hours of cardio, or elsewhere 660secs a week to show a considerable difference for overweight geeks. The theme is always "it only takes this teeny weeny amount to have an effect" - so why do more, right? Like we're off the hook then. I mean if all we need is 6 super intense minutes, the rest be dammed. We can get back to the screen.

What Systems Are Measured in Minimal Movement Studies?

But what's the effect? cardio vascular well being. Heavens knows that's important. But what about the rest of us? The respiratory and cardiovascular systems - the two most often discussed in health as part of "aeorbic fitness" - are only two of eleven physiological systems in the body. That leaves nine more to go. Consider the skin, skeleton, muscles, nervous system, hormones, lymph, sex, waste, digestion. What do they need? Turns out movement is pretty good for all of them.

To give one example, breathing is a big pump for lymph circulation and flushing. Exercise helps work breathing, so that has an impact on immune function. Movement, especially loaded work and c/v work, we know helps fascilitate nutrient uptake, and hormonal balance like insulin sensitivity. Stop/start movement like socer or weight lifting is great for our use-it-or-lose-em bones. Indeed we know that joints literally start to seize up from lack of movement in full range of motion, or develop pain conditions like RSI from overuse of one movement direction unbalanced by the others in that joint/muscle combination. It's amazing that we don't all keel over with *only* 20mins, 3 times a week of some kind of activity

Being Embodied Can be Fun

Brad Pilon made an observation on facebook lately

"Obesity. We concentrate on nutrition and exercise, but some other things are going on too. Did you know that 'sporting goods sales' have been steadily declining for the last several years? Why buy a soccer ball when you can buy fifa 2010? Hockey? that's what the Wii is for right? Bikes & skateboards? Too dangerous. There's excuses for it all, but still..lack of play time may be one of the biggest factors." July 23, 6:56 pm, 2010As an antidote, Frank Forencich at exuberant animal has an entire blog dedicated to movement/play. At the recent zhealth strength and sustenance course, we learned so many ways to move - including not moving but different forms of concentrics - or exhausting mircro movements - that it seems movement can be got from just about anywhere. And since one of the pay offs of movement can be endorphin rushes, finding any excuse to do it may just be the best thing in the world.

Also before the strength and suppleness course, we played frisbee at the end of the day. An hour of catch and a game of Ultimate each night and you've bagged your 5 hours without even thinking about it. The challenge is now to implement something similar back in Normal World.

Changing Perspective; New Discoveries.

Einstein is attributed with saying something to the effect that we can't solve our problems with the tools that created them. Easy for Mr. Paradigm Shifter I invented Relativity and topped Newtonian Physics guy to say, perhaps, but it's a salutory thought.

In this case, the fast food head space that wants what it wants now and for the minimal effort in order to go do something else - to not pay attention to what we eat; to not pay attention to how we move - is the problem, and trying to find a solution for our emotional (stress), physical and nutrional whiles with the least effort/time possible is entirely the wrong paradigm.

Maybe the paradigm shift is - what do i need to change to move the MOST i can during the day, the week, now? Related might be: What do i need to do to get the most pleasure from the best food today, to be present to being here as much as possible, to have the best rest tonight to concentrate the most i can on what i do now and later?

We're fully integrated, physical creatures, though our world is increasingly designed to shape us as brains with bodies. Abandoning that belief and moving towards the Movement Light as much rather than as little as possible feels and performs, it seems, a whole lot better - across all the rest of what we do, too, don't you think?.

Refs

Castelli DM, Hillman CH, Buck SM, & Erwin HE (2007). Physical fitness and academic achievement in third- and fifth-grade students. Journal of sport & exercise psychology, 29 (2), 239-52 PMID: 17568069Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Eveland-Sayers BM, Farley RS, Fuller DK, Morgan DW, & Caputo JL (2009a). Physical fitness and academic achievement in elementary school children. Journal of physical activity & health, 6 (1), 99-104 PMID: 19211963

Chomitz, V., Slining, M., McGowan, R., Mitchell, S., Dawson, G., & Hacker, K. (2009b). Is There a Relationship Between Physical Fitness and Academic Achievement? Positive Results From Public School Children in the Northeastern United States Journal of School Health, 79 (1), 30-37 DOI: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00371.x

Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, Plymate SR, Fishel MA, Watson GS, Cholerton BA, Duncan GE, Mehta PD, & Craft S (2010a). Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Archives of neurology, 67 (1), 71-9 PMID: 20065132

Berchtold, N., Castello, N., & Cotman, C. (2010b). Exercise and time-dependent benefits to learning and memory Neuroscience, 167 (3), 588-597 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.050

Labels:

bone health,

sustenance,

wellbeing,

zhealth

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

How get strong if (part of) our muscles aren't actually on?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

So that seems like a dumb question, doesn't it: how do we get strong if our muscles aren't actually on? After all, we work out; we get lots of reps in - we seem to get stronger, and then someone says about that plateau we're hitting "maybe the reason you're not getting that press is that you're weak." Excuse me? You talking to me?

That happened to me today. As some of you know i'm trying to get the 24kg KB press - hence the wee recent chat with Dan John about pressing. But today, at the 9S strength and suppleness course, one of the components was getting some muscles checked to see if they were firing on demand. Eg, anterior delt. Pretty important in pressing. What did i learn? It wasn't staying on through a good part of the range of motion possible of that muscle. Let me clarify - part of the muscle wasn't staying on through the ROM. In my case, close up to the origin was having a hard time. Just part. Consequence? Sucky press progress.

So we looked at ways to help a person (a) learn the range of motion of the muscle with respect to its action on a joint and (b) how to cue the person to get that part of that muscle to come on in that range of motion. Gotta tell you there were a lot of "Oh so that's what that muscle feels like when it's working" comments.

The big deal here is that we're talking about parts of the whole muscle - not the big "my glute med isn't firing" but "this part of my glute med at this ROM is not firing."

Why would we Care to get More Muscle going?

Contractions: Muscle fibers are wee wee things making up the body of a muscle. Motor units - nerves going to the bundles of muscles - don't all come on at once. But they also don't come on part way. THere's no dimmer switch to a muscle. They're either on or off. The strength of a contraction is relative to the number of motor units that come on. Another cool point is that the ratio of motor units to fibers changes depending on body parts. Hands, feet and eyes have for instance way way higher rations of motor unit to fibers than say the legs or the forearms. There's also issues around the squencing of motor units firing in a contraction, but we'll set that aside for the moment

So the potential to see the effect of motor unit shut down may be greater in the bigger muscles with fewer individual motor units per fiber.

Main point: If a bunch of motor units are not being recruited, or they turn off part way through a motion, we get squishy bits or what feels like dead zones in the body of the muscle.

Conversely, the more motor units firing, the more fibers get triggered, the more force can be produced, the more easily we lift - or the more load we lift and the smoother the lift that can keep the muscle on throughout the action. THis is likely a gross oversimplification that does not take into account recruitment patterns and wind speed etc, but it seems to work as a general model.

Example I had the pleasure to work with a great guy and super coach, big guy too, muscle wise, who said that he had trouble with his squat - his DL overtook it completely. By comparison his shoulders are beautiful. So let's see if those massive delts may also be associated with sans squishy recruitment.

WHen muscle testing his shoulders - the delts and the teres major in particular - everything was solid throughout the range of motion. No squishy bits (unlike mine). Wow. When we tested the quads it was quads be gone. They were just a sea of squishy bits. Wow.

Now, obviously this guy could squat me on his back all day long no problem, so he's not "weak" in the 99lb sand kicked in his face kinda way. But it's plain that he could be stronger and faster if more of the muscle was willing to come on.

Aside: Nervous System Perspective. Everything's connected.

In many cases that weekend, we worked on muscles, helped folks get squishy bits to come on more fully, and tested that yup performance was going up. And in some cases pain was going down at the same time.

With super coach's quads, we did not get so much action back in the legs. A bit of history revealed that super coach's biggest issue is plantar fascitis right now and that's his priority. It may be that in his case, his nervous system is not willing to pour more juice into his quads to let him go heavier if his base is in pain. Poor feet feeling, not so safe for adding greater load. Could be. So wisely super coach is focusing on what his bod is telling him to do.

In other cases, helping one muscle to fire better, helped an entire system to opening up and got people to a whole new level of happy.

Plugging in Muscle Work.

Learning to feel what a muscle feels like - what it's role is in a movement is an interesting exercise.

Here's where some kinesiology can help

Here's where some kinesiology can help - by knowing what muscle is reponsible for what action in a movement, we can see if it's doing its job to support that movement.

- by knowing what muscle is reponsible for what action in a movement, we can see if it's doing its job to support that movement.

This approach to performance checking is another reason why we all need a knowledgeable coach. If progress is stalling it may be that it can be addressed more rapidly by a quick anatomy function check to see if something needs a little attention to be brought to it to come to the party than looking at 20 different lift variations to see if that's the ticket. It's not to say that those lift variations aren't key plateau busters, but for them to function optimally, it would be better for them to be situated on an optimally functioning base, no? Accelerate progress.

A coach can cue our awareness of the muscle, it's ROM and check when it's coming off and help us practice attention to keep that part of a muscle on.

Tuning

Muscle work like this, it seems to me, is tuning. It's not the single factor foundation thing in itself that will solve all ills or create training shortcuts. It's a refinement on top of good movement quality to begin with and *then* tuning the muscles within this quality foundation.

It's polishing part of the global picture. But goodness what a big difference a little bit of polish, a little bit of tuning can make: the image is clearer; the music more harmonious - the effect more enlivening.

Muscle tuning in this way therefore seems to make great sense as part of a whole package of coaching/tuning for performance and well being: start with cleaning up whole movement (i like z-health r-phase for this); then dial it in even more with a coach who can offer muscle tuning (and more - like working in the wonderful world of ligaments - no kidding - but that's for another time).

Muscle tuning in this way therefore seems to make great sense as part of a whole package of coaching/tuning for performance and well being: start with cleaning up whole movement (i like z-health r-phase for this); then dial it in even more with a coach who can offer muscle tuning (and more - like working in the wonderful world of ligaments - no kidding - but that's for another time).

Related Posts

That happened to me today. As some of you know i'm trying to get the 24kg KB press - hence the wee recent chat with Dan John about pressing. But today, at the 9S strength and suppleness course, one of the components was getting some muscles checked to see if they were firing on demand. Eg, anterior delt. Pretty important in pressing. What did i learn? It wasn't staying on through a good part of the range of motion possible of that muscle. Let me clarify - part of the muscle wasn't staying on through the ROM. In my case, close up to the origin was having a hard time. Just part. Consequence? Sucky press progress.

So we looked at ways to help a person (a) learn the range of motion of the muscle with respect to its action on a joint and (b) how to cue the person to get that part of that muscle to come on in that range of motion. Gotta tell you there were a lot of "Oh so that's what that muscle feels like when it's working" comments.

The big deal here is that we're talking about parts of the whole muscle - not the big "my glute med isn't firing" but "this part of my glute med at this ROM is not firing."

Why would we Care to get More Muscle going?

Contractions: Muscle fibers are wee wee things making up the body of a muscle. Motor units - nerves going to the bundles of muscles - don't all come on at once. But they also don't come on part way. THere's no dimmer switch to a muscle. They're either on or off. The strength of a contraction is relative to the number of motor units that come on. Another cool point is that the ratio of motor units to fibers changes depending on body parts. Hands, feet and eyes have for instance way way higher rations of motor unit to fibers than say the legs or the forearms. There's also issues around the squencing of motor units firing in a contraction, but we'll set that aside for the moment

So the potential to see the effect of motor unit shut down may be greater in the bigger muscles with fewer individual motor units per fiber.

Main point: If a bunch of motor units are not being recruited, or they turn off part way through a motion, we get squishy bits or what feels like dead zones in the body of the muscle.

Conversely, the more motor units firing, the more fibers get triggered, the more force can be produced, the more easily we lift - or the more load we lift and the smoother the lift that can keep the muscle on throughout the action. THis is likely a gross oversimplification that does not take into account recruitment patterns and wind speed etc, but it seems to work as a general model.

Example I had the pleasure to work with a great guy and super coach, big guy too, muscle wise, who said that he had trouble with his squat - his DL overtook it completely. By comparison his shoulders are beautiful. So let's see if those massive delts may also be associated with sans squishy recruitment.

WHen muscle testing his shoulders - the delts and the teres major in particular - everything was solid throughout the range of motion. No squishy bits (unlike mine). Wow. When we tested the quads it was quads be gone. They were just a sea of squishy bits. Wow.

Now, obviously this guy could squat me on his back all day long no problem, so he's not "weak" in the 99lb sand kicked in his face kinda way. But it's plain that he could be stronger and faster if more of the muscle was willing to come on.

Aside: Nervous System Perspective. Everything's connected.

In many cases that weekend, we worked on muscles, helped folks get squishy bits to come on more fully, and tested that yup performance was going up. And in some cases pain was going down at the same time.

With super coach's quads, we did not get so much action back in the legs. A bit of history revealed that super coach's biggest issue is plantar fascitis right now and that's his priority. It may be that in his case, his nervous system is not willing to pour more juice into his quads to let him go heavier if his base is in pain. Poor feet feeling, not so safe for adding greater load. Could be. So wisely super coach is focusing on what his bod is telling him to do.

In other cases, helping one muscle to fire better, helped an entire system to opening up and got people to a whole new level of happy.

Plugging in Muscle Work.

Learning to feel what a muscle feels like - what it's role is in a movement is an interesting exercise.

This approach to performance checking is another reason why we all need a knowledgeable coach. If progress is stalling it may be that it can be addressed more rapidly by a quick anatomy function check to see if something needs a little attention to be brought to it to come to the party than looking at 20 different lift variations to see if that's the ticket. It's not to say that those lift variations aren't key plateau busters, but for them to function optimally, it would be better for them to be situated on an optimally functioning base, no? Accelerate progress.

A coach can cue our awareness of the muscle, it's ROM and check when it's coming off and help us practice attention to keep that part of a muscle on.

Tuning

Muscle work like this, it seems to me, is tuning. It's not the single factor foundation thing in itself that will solve all ills or create training shortcuts. It's a refinement on top of good movement quality to begin with and *then* tuning the muscles within this quality foundation.

It's polishing part of the global picture. But goodness what a big difference a little bit of polish, a little bit of tuning can make: the image is clearer; the music more harmonious - the effect more enlivening.

Muscle tuning in this way therefore seems to make great sense as part of a whole package of coaching/tuning for performance and well being: start with cleaning up whole movement (i like z-health r-phase for this); then dial it in even more with a coach who can offer muscle tuning (and more - like working in the wonderful world of ligaments - no kidding - but that's for another time).

Muscle tuning in this way therefore seems to make great sense as part of a whole package of coaching/tuning for performance and well being: start with cleaning up whole movement (i like z-health r-phase for this); then dial it in even more with a coach who can offer muscle tuning (and more - like working in the wonderful world of ligaments - no kidding - but that's for another time). Related Posts

- What is z-health

- Pelvis Power - working hip opening in the press.

- the other side of the gym: sensory motor work

- Fatigue testing: is the next rep one too many

Labels:

strength,

strength as a skill,

z-health,

zhealth

Monday, March 15, 2010

Sports Training on the other side of the weight room with Sensory-Motor Perception

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Does Make me Stronger Make Me a Better Athlete? When athletes talk about getting stronger for their sport, what's the goal behind that quest? Is that because we think that strength is the missing ingredient that will actually make us *better* athletes in a game situation? If so, why? We want to hit the ball harder, throw faster, kick further and we think strength's it? Is that the key part of our game that's weak? And if that's it, is raw strength the real issue?

If we're swinging a bat, and our hips and pelvis move as a unit rather than serially into the swing (bacause they can't move separately), that's a power leak that where more strength mayn't make much of a performance difference without correcting that hip/pelvis issue. If we're going to grab the bar for a deadlift but our wrist mobility is shonky, are we going to be able to control our grip with the strength it takes to make the pull? More leg strength isn't the issue. If we want to kick a football really far but our balance is off so our coordination is a bit askew, more power may continue to be directed away from optimal contact.

likewise, there's a lot of decision processing going on whether on the court or on the field, right? Our brains are making tons of decisions so quickly from where to put a ball on the opponent's side of the tennis court, to where the best path is to run a ball down the field, to who's open for a shot. If we're not really seeing the field, we can't make optimal decsisions about it.

So maybe we need to consider the sensory-motor connections of visural, vestibular and proprioceptive perception and associated skills to enhance our sports performance training. Each of these systems can be trained deliberately to behave more reflexively to these very normal sports situations.

In the following sections, we'll look at these areas of the sensory-motor processing within our sensory systems AND there'll be some quick self-checks you can run to check parts of these perceptual systems' performance. We'll also consider the time a person would have to put into this program to see real performance change, and i've peppered in links for resources either to doing each bit at a time, or training to put each part together at once.

The goal is that with this overview you can begin to ask the questions - and have some answers - about how to assess yourself in terms of performance, not just strength. You may find that your strength simply improves as a consequence of better work here, too.

Tuning Sensory-Motor Performance.

By way of a quick overview the proprioceptive system, as i've written about at b2d rather a bit, is the monitoring system in our bods that lets us know what's happening to us from a range of awarenesses: pressure, temperature, chemical shifts, elecro-magnetical sensing, and particular for athletic movement, positional and noxious (aka pain in many cases) awareness.

For positional awareness, we're wired up with propriocpetive mechanorecptors ( a special class of mechnoreceptors), with a good many of them being around the joints, the bendy bits of the body (makes sense - good to know where the mobile parts of a limb can be) and in the musles that detect stretch, motion, pressure. This being the case - that these receptors convey alot about the state of our limbs moving in space - the corollary of this is the better a joint can move, or the better the range of motion and the control of that range of motion around a joint, the better the information that joint is putting out.

Eric Cobb talks about this enriched sensory action as "map clarity" - the more data points the more detailed the map; the more mechanoreceptors available to give positional information the more options the body has about where and how it can go somewhere. If there's restrictions in the ankle or knees so that range of motion is not available there's in effect a sensory deprivation and a performance decrement: the body doesn't tend to go down blind alleys; it makes the best decisions it can based on the available map. Which can mean - you body don't have the resources to step quickly over that stump, you're going down suddenly. Ugh! shock! sprain!

Eric Cobb talks about this enriched sensory action as "map clarity" - the more data points the more detailed the map; the more mechanoreceptors available to give positional information the more options the body has about where and how it can go somewhere. If there's restrictions in the ankle or knees so that range of motion is not available there's in effect a sensory deprivation and a performance decrement: the body doesn't tend to go down blind alleys; it makes the best decisions it can based on the available map. Which can mean - you body don't have the resources to step quickly over that stump, you're going down suddenly. Ugh! shock! sprain!

Similarly if an athlete's restricted in their hips for instance (the hip and pelvis behave like a fused unit rather than separate joints) how the heck are they going to perform optimally? What will pay for this lack of mobility? the Low back maybe?

Preliminary Assessment

So one key part of athletic training can be a good movement assessment before any training takes place. An assessment helps discover where an athlete may need to do some work to reduce restrictions in mobility in order to open up better movement options - and thus the athlete has a better set of options for responding to situations without getting hurt when in play: yes the body has a very clear sense of where it is and (b) with lots of range of motion available, has more options for moving the ankle rather than going over on it.

At an even more basic level, mobility work is simply the practice of the joint movements to make sure an athlete can they move the joints well on demand and effortlessly.

Aside: such assessments can also check visual and vestibular performance too.

Movement Quick Check: Here's a simple check you can do with yourself or your athletes to explore joint freedom for greater movement options. Stick a leg out in front of you, and then put the leg out and straight so that it crosses the body where the foot of the outstretched leg goes past the foot of the stance leg. Check in a mirror: is the pelvis torquing around to let the leg reach this far? Now make little circles there with the knee locked out and the leg crossed over: is the pelvis torqued over? still? going up and down? If the pelvis is still and not torqued forward as if moving towards the other leg, in that position at that speed, super. Try going slower and faster. Still good? super duper. If not, that may be a sign that the pelvis and hip don't know how to work independent of each other - and so the mechanoreceptive information is less clear/accurate, and the functional options for movement less optimal. Mobility work can often address this and recover that more discrete hip/pelvis function.

Time to train: every joint in the body takes 10 mins a day, once a day. Can work different speeds/drills on different days.

Roles: So mobility work has two main functions: (1) ensuring optimal signal for optimal options of movement in live situations (Example programs for self-development).; (2) practicing movements in a variety of positions with the joints so that getting into weird (eg accident) type positions are not shocking, but relatively adaptable (program for self-dev)

Vestibular Acuity.

The middle of the neural hierarchy is the inner ear: it is predominantly the balance system of the body. BUT it also relates to motion detection, proprioception and even muscle tone. Everything is interconnected. That's really critical to understand that these systems in the neural hierarchy are not independent of each other: an issue in one has consequences in the other, and multiple systems contribute to different degrees in different contexts to the same thing. Here, for short hand, we're focusing on the balance role of the vestibular system.

The balance system is mainly located in the inner ears. We have two inner ears - one for each ear. That sounds obvious, but just like each eye may be slightly different in strenghts/weaknesses, likewise the inner ears may have different dominances. How well are they behaving in general to support sports movement? And how well are they behaving in concert?

ear. That sounds obvious, but just like each eye may be slightly different in strenghts/weaknesses, likewise the inner ears may have different dominances. How well are they behaving in general to support sports movement? And how well are they behaving in concert?

Assessments of the vestibular system may show a discrepency on either side specifically, or generally that there may be some weaknesses. The cool thing is, the balance system can be trained. Intriguingly this doesn't mean stepping onto unstable surfaces. IT may mean skills development on very stable surfaces (see middle of this post) .

Quick Test: Here's an example. Stand on one foot for more than fifteen seconds. Now stand on the other. Is one side more wobbly than the other? Why is that? How common is it for someone on a sports field to have one leg off the ground at a time? So might it be valuable to ensure that one can be as stable as possible in that circumstance?

Time to train: 3x's a week, 10 mins/session, 8 weeks. Then maintenance.

Visual Accuity

At the top of the neural hierarchy is visual acuity - not eye sight, but they get sports vision evaluations to see how they're doing, and they practice visual acuity (here's one example) so that they can respond quickly to what's happening on the field - so their ability to perceive the situation under pressure improves.

When we work on visual accuity, we not only look at the function of the two eyes and how well they're working together, but we also work on improving the time, complexity and distractions that can be processed concurrently for quicker visually lead responses to action in the environment.

Quick Test - check out the near/far drill modelled in the link above.

Time to train: basic drills, 2 mins a day, can be combined with mobility work.

Practice sessions for cognitive load, 15 mins a day, 3times a week, 8 weeks, then maintenance.

Great program for self-development: great visual drills and speed work, too.

Putting This Sensory-Motor Work into Practice: Speed/Quickness:

As said in vision, we work with athletes to improve visual acuity of eye performance like speed of changing focus, but also work on processing dynamically changing visual information more quickly. When we have discrete loaded mobility, balance and visual acuity firing, we can also consider putting these together at "sports speed."

But speed is also a skill, too. Strength and conditioning has for awhile now been looking at sprining mechanics and technique and training - like plyometrics - to improve quickness. All sorts of things like towing a partner or being towed can get into faster turn over.

There are other techniques, too, though, that have to do with putting all the mobility and visual and vestibular accuity to work to move quickly and more efficiently at quickness. So sometimes speed is speed, but sometimes it's being faster in response to something than the opponent.

Speed in Context.

This one seems so obvious - to move fast is a good thing. And that's where our example athlete came in at the beginning: someone who wanted to move faster (i think that's what the fast twitch is about) but the skills described here would be not about making the person faster once they're up and running (how far do they have to go on a field?) but

I've bet guys much younger than i am that i can beat them getting turned around or i can get a faster start off the line from a standing start than they. What's the difference? Technique and practice of technique for moments of change where the technique is efficient and it respect the brilliance that is the athletic ready position.

Strength: what kind of strength. Finally, after all the above neural stuff happens, we might want to come back to the question: so do you really need to be stronger in your current deadlift to be a better socer player?

I generally find that most guys who have been playing for awhile are plenty strong on the teams but their endurance in the last part of the game can flag. So if anything gets added to the program, kettlebells can be great and very efficient for brute strength and stamina: two simple moves - swings and turkish get ups.

Quick Test If ya don't believe me, try this for ten minutes:

- (assuming you know how to swing a kb safely) you swing a heavy kb while your partner TGU's left and right with a medium bell, then swap and keep going non-stop for ten minutes. These two moves have the advantage of also developing hip and lat strength, pretty key for that athletic ready position.

Time to train - 20-40 mins every other day except in season. In season, coach's discretion.

Ask any coach if the strongest athlete in the dressing room is their best athlete on the field.

Taking the Pieces Further: getting more drills and skills and program plans. If the above kinda program sounds interesting to you, beyond the links to various bits above, there's a three day workshop that gives a great intro to self-assessment and practice on this performance pyramid of vision, vestibular, proprioception calledessentials of elite performance (overview).

Some of us also coach this stuff (look for S-phase (review) in the training certifications). If you can't find someone in your neighborhood, i also coach via email/skype. Contact me with the email link at the bottom of this post if you're interested in neural hierarchy for sports training.

Take Away: Better is not necessarily Stronger.

Assuming the goal is to be a better field player, not just stronger, there may be more and other ways to look at performance than just raw strength. And that OTHER which we may often think of as rather fixed - vision, balance, movement - is highly plastic and trainable. When we start with the nervous system, too, the biomechanics seem to come online, stronger, faster, better.

Assuming the goal is to be a better field player, not just stronger, there may be more and other ways to look at performance than just raw strength. And that OTHER which we may often think of as rather fixed - vision, balance, movement - is highly plastic and trainable. When we start with the nervous system, too, the biomechanics seem to come online, stronger, faster, better.

Update: related new resource (may 2010)

DVD Mini Course - 6.5 hours of the essentials of elite performance workshop on three divds. If you can't make the workshop, or just want to get going on this stuff NOW, this new dvd mini course is a great way to get going. I'll have a full review soon, but in the meantime, there's way more self-tests and practices than covered above. Please check the link for the full nine yards on the details.

Get it, love it, sign up for the essentials workshop or R-phase cert (overview) within 30 days of purchase and get $100 off tuition of either course.

Great way to get a richer sensory-motor training tool box and tune up. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

If we're swinging a bat, and our hips and pelvis move as a unit rather than serially into the swing (bacause they can't move separately), that's a power leak that where more strength mayn't make much of a performance difference without correcting that hip/pelvis issue. If we're going to grab the bar for a deadlift but our wrist mobility is shonky, are we going to be able to control our grip with the strength it takes to make the pull? More leg strength isn't the issue. If we want to kick a football really far but our balance is off so our coordination is a bit askew, more power may continue to be directed away from optimal contact.

likewise, there's a lot of decision processing going on whether on the court or on the field, right? Our brains are making tons of decisions so quickly from where to put a ball on the opponent's side of the tennis court, to where the best path is to run a ball down the field, to who's open for a shot. If we're not really seeing the field, we can't make optimal decsisions about it.