Showing posts with label z-health. Show all posts

Showing posts with label z-health. Show all posts

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Unpacking a mystery: when shoulder pain may be all (or largely) in the wrist (a t-phase assessment story)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Pavel tells the joke about asking people in a weight room "so those of you who have had a shoulder injury, raise your hands" - half the people raise their hands; the other half can't.

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

mc

Related Posts

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

1) pain in the biceps: there's that biceps tendon going into the shoulder - address that, and guess what - pain HUGELY reduced.

2) help out the brachioradialis/extensors (esp carpi radialis perhaps) overlapping tendon/musle area, there's more relief (nerve work for the radial nerve included).

3) muscle test some of those extensors and there's squishy bits - get that fixed so the whole extensor is firing, more relief.

4) pay attention to the axilary nerve that fires the deltoids, and the posterior delt starts to come back on line (have some more work to do there but heck it's work i know how to do).

5) do a wee bit of hybrid minimal t-phase style kinesio taping around the long head bicpes tendon area, matched up with active dynamic joint mobility drills for the shoulder, elbow and extensors, and things start to simmer down

6) work out some of the fascial stickiness around the extenors with v.light hybrid t-phase fascial work

7) get some exercises for working the extensors in particular,

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

Personal Practice So suggestion? If you're having hinky performance/pain issues, check in with a movement performance specialist. Here's a trainer listing. If you'd like a referal, call the office, and let them know mc suggested you ask them.Best with your practice,

mc

Related Posts

- Tendinopathy, tendinitis and Eccentric Exercise for rehab

- Ensuring that the *whole* muscle fires in a movement for real strength

- Why not move through pain

- dealing with chronic back pain

- active vs passive care/therapy

Saturday, August 14, 2010

A Model of an Athlete, of Athletecisim: z-health's 9s - also a model of coaching

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Here's a question that seems to be poking me on from the earlier "do we enjoy all our workouts/practices/training sessions?" And it's: What is our model of performance? what are the qualities to which we aspire in terms of living what i'm increasingly seeing as "embodied" lives - where we get that we're not just brains with bodies, but that our bodies are life enhancing? Before answering this, one might wonder why do we need a model? Why not just you know, keep moving? Eat well, rest well, move well.

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People demonstrates why

demonstrates why having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great  attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First

and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First  is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

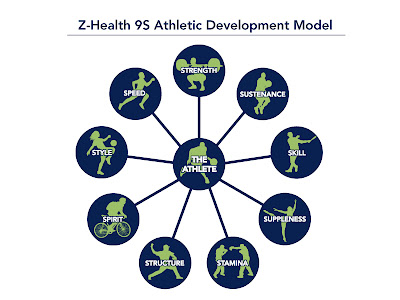

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated , and as Gladwell notes in Outliers

, and as Gladwell notes in Outliers , putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

, putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

|

| The Z-Health 9S model of the Athlete |

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

9S,

coach,

principles,

z-health,

zhealth

Thursday, August 12, 2010

The Eyes Have It - sometimes: using eye position to enhance strength

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

I was fascinated by Geoff Neupert's article in the latest Power by Pavel Newsletter (issue 209, 08/09/10) about his experience using eye position in the press. Geoff is the author of Kettlebell Muscle. Absolutely awesome to see eye position highlighted in relation to how that action can support movement practice. That support is rather dependent on where and how in a compound move it's being used, and also what else may be happening in our somato-sensory systems. So let's look at eye position and postural reflexes and how they support muscle action a little more.

I was fascinated by Geoff Neupert's article in the latest Power by Pavel Newsletter (issue 209, 08/09/10) about his experience using eye position in the press. Geoff is the author of Kettlebell Muscle. Absolutely awesome to see eye position highlighted in relation to how that action can support movement practice. That support is rather dependent on where and how in a compound move it's being used, and also what else may be happening in our somato-sensory systems. So let's look at eye position and postural reflexes and how they support muscle action a little more.

Geoff writes:

Geoff reports that this didn't work for him. When we understand the roll of vision in position, that result is not surprising, so we'll come onto why. He then proposes a revised move with a different head, jaw and eye position: the neck back a bit, chin up a bit and eyes slightly up.

Geoff says of this approach:

Test Early; Test Often The key thing to me in this article is that Geoff did "test" his new approach: did it improve his press? he says so an i believe him. Yet while he proposes a new technique for his press, and has some interesting theory to support it, whether or not that approach will be universally successful may be as likely as eyes down through the lift was successful for Geoff. May be. Dunno, maybe.

The take away from this story, at least for me, is less about a new technique that will work for everyone and more about: test it, because what works for you mayn't work for me, or for you later today, no matter how well we hypothesize why something works after the fact.

Let me step back a bit and say here's why i'm not surprised by GN reporting that eyes looking down *through the whole press* would likely/potentially not be a good idea: there's more going on than shoulder flexion in the press.

Eye Position and Reflexes when Reflexes work. Let me back up even further and say that the eyes are tied to reflexes that support extension, flexion, adduction, abduction, rotation. By reflex we mean involuntary automatic and near immediate response to a stimulus. Intriguingly, sometimes these reflexive responses can get buggered up, (and with the eyes, have particular effects on posture, among other things) but more on that anon.

When things are working right, we see looking down triggers flexion, looking up triggers extension looking in one direction triggers complementary adduction/abduction/rotation in the direction viewed.

Eye position is then used to complement/strengthen what can most benefit from that reflex. That may change throughout a lift. And what if while one thing is extending something else is flexing? What do we need help with the most? We'll look at an example to try in a sec.

Strengthening what needs to be strengthened throughout a lift

As an example of how eye position might change in a lift, let's take a look at the example from Geoff's article, the kettlebell press. The press is a rich movement: one may need eyes down to support shoulder flexion at the beginning of the lift coming out of the rack, then eyes towards the horizon and looking at the bell when the delts are at the weakest point, so strengthening rotator cuff movements, and post sticking point, eyes up to support the triceps extending (thanks to conversations last year with Zachariah Salazar Z-Health Master Trainer and RKC on these multiple positions in the press). In Pavel's pressing, as RKC Ken Froese pointed out to me, his eyes seem to follow the bell throughout, which may be great for someone with even strength, but not for someone with say a shoulder issue.

So keeping eyes down throughout the movement may be less productive for some people if where the weak link in the move shifts, and changing eye position will enhance that.

Try this at Home: A chin up (hands supinated) uses extension of the shoulder/lats firing, but it also uses elbow flexion (biceps coming into a curl). So what needs more help for you in a chin? Best way to find out: test either/or positions, depending if one's weaker link is shoulder extension/lats (eyes up) or biceps flexing (eyes down). Try both: what works better for you -when? Which is which may change as training progresses, or for just about any other reason, as we'll see below.

When reflexes seemingly aren't firing normally

Why would a doctor whack a knee if a reflex always fired as it was supposed to? We wouldn't need to test something that always works one way. Same thing with eye responses as demonstrated in what are referred to as postural reflexes, richly informed by the visual (and vestibular and proprioceptive) system(s):

Sometimes due to trauma or sometimes a long flight and jet lag, one's postural reflexes get really muted or actually cause the inverse effect reflexively in the body. There are tests for this (if you visit with a z-health certified coach who's done i-phase, for instance, they'll know these position/vision tests). The important thing to get is that our muscular responses - things as seemingly simple and immutable as flexion and extension - are intertwined with the somato-sensory system (visual, vestibular and proprioceptive function), and that these intertwined systems are constantly dealing with various stimuli. As Reiman and Lephart found in 2002:

Obviously, if one's visual responses to a direction are screwed up (say looking down doesn't strengthen your bicep curl, or cue an appropriate postural reflex), then using your eyes in a movement in that direction is also likely not going to help - in some cases it may seem to work against you if your body doesn't like that eye position, performance is going to suffer - until the thing gets fixed. And it is addressable.

Repetez après la model: Test It. So rather than getting super prescriptive about what will achieve what, great to have some heuristics about reflexes and eye position and of course form. But great too (a) to be sure to be able to refine application - like multiple eyes positions may be needed throughout a move and (b) to know that those reflexes are working as designed and (c) just test it.

If an eye position doesn't work - doesn't provide a performance boost or takes away from one - try something else. And if in a simple move like a biceps curl where eyes down should make that curl stronger and it doesn't work, maybe check with that qualified coach who knows how to work with these positions in case it's either a technique thing or something else that may need a bit of work.

We are Complex Integrated Systems There are 11 systems in the human being. They all interact with one another, from our skin to our reproductive system. There's no way we're going to be able know, a priori, what will unequicoably work for ourselves, little own everyone at all times. only salespeople seem to make such unequivocable claims about their products - it slices; it dices. always for everything. Really? What other domain is so certain?

In my main domain of human factors, this is why we can't make claims about the effectiveness of an interface based on how it works for ourselves alone, but have to test it rigerously so that we can say with some statistical power that it is effective to some degree, and even that is constrained like: for people aged x-y with these particular skill sets, they were able to use this tool to complete this task A% better than the previous tool design. Without that - even though we've developed that design with the best models of human performance from motor control to cognition available to us - the best we can say in our domain is "we liked it; why don't you give it a try and let us know if it worked for you."

Broken Record: Test it. Frequently, regularly. Vision is a potent system - the top of the somato sensory hierarchy. Makes sense that when it's firing well, it can help our other systems respond well. To use eye position to enhance a lift, therefore, means testing the eye position to see what action in a lift may need that enhancement - presuming that our visual reflexes are working as they're supposed to work. So again, if eyes down doesn't enhance that biceps curl, may be time to check vision, too. If it is, check eye position with the move. Test various positions through the move.

It's a really simple principle. It means having strategies to deal with a weak result to help make improvements. but at the very least it gives us information about tuning what we're doing.

Citation

Related Posts

Geoff writes:

For the last four years, until recently, I promoted a neutral head, eyes down posture for presses and jerks, thinking that this would increase flexion at the shoulder and therefore increase shoulder mobility and allow for the weight to go up easier.

Geoff reports that this didn't work for him. When we understand the roll of vision in position, that result is not surprising, so we'll come onto why. He then proposes a revised move with a different head, jaw and eye position: the neck back a bit, chin up a bit and eyes slightly up.

Geoff says of this approach:

This is excellent: Geoff tested the move to see if it worked better for him, today. Testing a technique is critical as adaptation is pretty individual; testing that neutral head / eyes down thing sooner might have been a good idea too for addressing four years of press frustration.I then corroborated my findings with what the absolute best in the world do, confirmed my position, applied my "new" techniques, and started making progress once again.

| |

| For more ideas on how to train these eye muscles, see Eye Heatlh: How Fast can you switch focus? |

Test Early; Test Often The key thing to me in this article is that Geoff did "test" his new approach: did it improve his press? he says so an i believe him. Yet while he proposes a new technique for his press, and has some interesting theory to support it, whether or not that approach will be universally successful may be as likely as eyes down through the lift was successful for Geoff. May be. Dunno, maybe.

The take away from this story, at least for me, is less about a new technique that will work for everyone and more about: test it, because what works for you mayn't work for me, or for you later today, no matter how well we hypothesize why something works after the fact.

Let me step back a bit and say here's why i'm not surprised by GN reporting that eyes looking down *through the whole press* would likely/potentially not be a good idea: there's more going on than shoulder flexion in the press.

Eye Position and Reflexes when Reflexes work. Let me back up even further and say that the eyes are tied to reflexes that support extension, flexion, adduction, abduction, rotation. By reflex we mean involuntary automatic and near immediate response to a stimulus. Intriguingly, sometimes these reflexive responses can get buggered up, (and with the eyes, have particular effects on posture, among other things) but more on that anon.

When things are working right, we see looking down triggers flexion, looking up triggers extension looking in one direction triggers complementary adduction/abduction/rotation in the direction viewed.

Eye position is then used to complement/strengthen what can most benefit from that reflex. That may change throughout a lift. And what if while one thing is extending something else is flexing? What do we need help with the most? We'll look at an example to try in a sec.

Strengthening what needs to be strengthened throughout a lift

As an example of how eye position might change in a lift, let's take a look at the example from Geoff's article, the kettlebell press. The press is a rich movement: one may need eyes down to support shoulder flexion at the beginning of the lift coming out of the rack, then eyes towards the horizon and looking at the bell when the delts are at the weakest point, so strengthening rotator cuff movements, and post sticking point, eyes up to support the triceps extending (thanks to conversations last year with Zachariah Salazar Z-Health Master Trainer and RKC on these multiple positions in the press). In Pavel's pressing, as RKC Ken Froese pointed out to me, his eyes seem to follow the bell throughout, which may be great for someone with even strength, but not for someone with say a shoulder issue.

So keeping eyes down throughout the movement may be less productive for some people if where the weak link in the move shifts, and changing eye position will enhance that.

Try this at Home: A chin up (hands supinated) uses extension of the shoulder/lats firing, but it also uses elbow flexion (biceps coming into a curl). So what needs more help for you in a chin? Best way to find out: test either/or positions, depending if one's weaker link is shoulder extension/lats (eyes up) or biceps flexing (eyes down). Try both: what works better for you -when? Which is which may change as training progresses, or for just about any other reason, as we'll see below.

When reflexes seemingly aren't firing normally

Why would a doctor whack a knee if a reflex always fired as it was supposed to? We wouldn't need to test something that always works one way. Same thing with eye responses as demonstrated in what are referred to as postural reflexes, richly informed by the visual (and vestibular and proprioceptive) system(s):

Visual and vestibular input, as well as joint and soft tissue mechanoreceptors, are major players in the regulation of static upright posture. Each of these input sources detects and responds to specific types of postural stimulus and perturbations, and each region has specific pathways by which it communicates with other postural reflexes, as well as higher central nervous system structures.There's even work to suggest that blinking or performing visual sacades may improve postural stability.

Sometimes due to trauma or sometimes a long flight and jet lag, one's postural reflexes get really muted or actually cause the inverse effect reflexively in the body. There are tests for this (if you visit with a z-health certified coach who's done i-phase, for instance, they'll know these position/vision tests). The important thing to get is that our muscular responses - things as seemingly simple and immutable as flexion and extension - are intertwined with the somato-sensory system (visual, vestibular and proprioceptive function), and that these intertwined systems are constantly dealing with various stimuli. As Reiman and Lephart found in 2002:

Motor control for even simple tasks is a plastic process that undergoes constant review and modification based upon the integration and analysis of sensory input, efferent motorWe occaisionally really get how intertwined these actions are if we ever have an inner ear infection, or find ourselves experiencing sea sickness or dizziness.

commands, and resultant movements.

Obviously, if one's visual responses to a direction are screwed up (say looking down doesn't strengthen your bicep curl, or cue an appropriate postural reflex), then using your eyes in a movement in that direction is also likely not going to help - in some cases it may seem to work against you if your body doesn't like that eye position, performance is going to suffer - until the thing gets fixed. And it is addressable.

Repetez après la model: Test It. So rather than getting super prescriptive about what will achieve what, great to have some heuristics about reflexes and eye position and of course form. But great too (a) to be sure to be able to refine application - like multiple eyes positions may be needed throughout a move and (b) to know that those reflexes are working as designed and (c) just test it.

If an eye position doesn't work - doesn't provide a performance boost or takes away from one - try something else. And if in a simple move like a biceps curl where eyes down should make that curl stronger and it doesn't work, maybe check with that qualified coach who knows how to work with these positions in case it's either a technique thing or something else that may need a bit of work.

We are Complex Integrated Systems There are 11 systems in the human being. They all interact with one another, from our skin to our reproductive system. There's no way we're going to be able know, a priori, what will unequicoably work for ourselves, little own everyone at all times. only salespeople seem to make such unequivocable claims about their products - it slices; it dices. always for everything. Really? What other domain is so certain?

In my main domain of human factors, this is why we can't make claims about the effectiveness of an interface based on how it works for ourselves alone, but have to test it rigerously so that we can say with some statistical power that it is effective to some degree, and even that is constrained like: for people aged x-y with these particular skill sets, they were able to use this tool to complete this task A% better than the previous tool design. Without that - even though we've developed that design with the best models of human performance from motor control to cognition available to us - the best we can say in our domain is "we liked it; why don't you give it a try and let us know if it worked for you."

Broken Record: Test it. Frequently, regularly. Vision is a potent system - the top of the somato sensory hierarchy. Makes sense that when it's firing well, it can help our other systems respond well. To use eye position to enhance a lift, therefore, means testing the eye position to see what action in a lift may need that enhancement - presuming that our visual reflexes are working as they're supposed to work. So again, if eyes down doesn't enhance that biceps curl, may be time to check vision, too. If it is, check eye position with the move. Test various positions through the move.

It's a really simple principle. It means having strategies to deal with a weak result to help make improvements. but at the very least it gives us information about tuning what we're doing.

Citation

Morningstar, M., Pettibon, B., Schlappi, H., Schlappi, M., & Ireland, T. (2005). Reflex control of the spine and posture: a review of the literature from a chiropractic perspective Chiropractic & Osteopathy, 13 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-16

Riemann BL, & Lephart SM (2002). The Sensorimotor System, Part II: The Role of Proprioception in Motor Control and Functional Joint Stability. Journal of athletic training, 37 (1), 80-4 PMID: 16558671

Rougier P, Garin M (2007). Performing saccadic eye movements or blinking improves postural control. Motor control, 11 (3), 213-23 PMID: 17715456

Related Posts

- Why I - train for the sprain

- THe other side of the gym - training the somato-sensory system

- more stuff about integration of systems: z-health overviews.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Bendy bits should bend in full range of motion, speed and control, right? So what's this mobility/stability dichotomy?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Mobility/Stability. I confess i don't get what's meant or how this increasingly popular distinction between mobility and stability came to be seen as useful. I'm prepared to believe it's my problem, and sometimes as writing helps me work out such issues, forgive me while i lay out where the gaps seem to be in my understanding of the framing of movement as mobility/stability rather than simply a notion of movement, and ability to control ranges of motion at ranges of speed.

Here we go: Of late i've seen a number of intelligent people assert with what seems like good reasons that some joints are seemingly a priori meant to be "stable" while others are meant to be "mobile." Consider the fist article in this set kicked off by Mike Boyle, a well respected and established trainer, called A Joint by Joint Approach to Training. In this pieces, and many related articles, work by Stuart McGill on the low back is cited: in particular, McGill's findings that flexion is the root of most low back evils, and that sitting is the worst place to be of all. This is pretty compelling stuff. Seems to make sense.

But then there are seeming contradictions within this: in his discussion of the knees, not the back, Boyle sites McGill's reason for low back pain that it isn't perhaps so *much* flexion, but overuse. When other stuff - like the hips - get stuck, the back pays. So in that sense - the lumbar spine and knees should be stable, but the hips should be mobile?

The problem i find in this is that the arguments seem to suggest that pretty much all the time the lower spine should be stiffened up and the thoracic spine and hips loosened up - for instance. Mike Boyle goes so far as to ask "is spinal rotation even a good idea" He quotes a lot of work by a physical therapist name of Shirely Sharman who in her view suggests that the abs are there to stop so much rotation of the lumbar spine then that's what they should be doing. Boyle's issue seems to be that too many trainers concentrate on lumbar stretching when, citing Sharman "rotation is even dangerous" at the lower spine. He points to sprinter coach Bob Ross who did isometric work with his spinters in the abs, abandoning other forms of spinal movement work and how that was a positive thing for results.

Ok, but what do most sprinters do? Run. In pretty much straight lines. So maybe holding the spine in line and upright for 10-30secs is a good idea. In that case. That particular sport-specific constraint doesn't come up.

Rather, Boyle says he's chucked a lot of exercises designed to extend trunk range and seems to find less complaints of low back pain in clients since doing so. And that's cool. I'm not sure, however, that that means that that work has made his client's backs more stable - it just may mean that stretching a body part beyond its comfortable range of motion is painful or causes neuroligical shut down by pushing inappropriately, and that stopping doing something that hurts will reduce pain?

In other words, i'm just not sure that eliminating a set of kind of questionable stretches is therefore "decreasing mobility" or "increasing stability" - it may just be avoiding inducing threat.

And as for rotational work, surely the lack of it is one of the greatest weakness of most of us who train especially or exclusively at lifting heavy things? We tend to stick to pretty a given plane of motion for a movement, and forget about diagonal and especially rotational movements.

One of the funest ab exercises is surely the russian twist (seated) or the Full Contact Twist with the bar stuck in the corner on the floor and the other end in the athlete's hands, arms extended, arc'ing back and forth?

Pavel Tsatsouline writes of the FCT in Bullet Proof Abs:

So for truly "functional" movement, isn't it better to train strength in rotation, as well as across a range of movement planes? In other words, why not focus on building strength across the entire range of motion of the joints so that we can be - as pavel puts it - bulletproof? And that bulletproofness seems to mean being able to rotate, bend and recover as needed - and as the joints give us the degrees of freedom to accomplish that movement?

The Kneee/ACL injury- not about stability or mobility? The ACL (and MCL) are the ligaments most often torn (or pop) in knee injuries. One might say that that's because the knees are not stable enough. Indeed, again Mike Boyle tends to make this case in his Joint by Joint article. But he also seems to move away from actually saying the knee needs stability by deeking out to say the problem is that the knees pay for lack of hip mobility. I'm not sure what the bottom line is here? He digresses into back pain rather than a discussion of the knee.

Gray Cook comes in to help in his Expanding on the Joint-by-Joint approach saying,

I'm not making a joke here or being sarcastic. I'm really not sure what "the knees have a tendency towards slopiness" means in terms of real movement. All those ligaments are actually loose? Or does that mean one's leg muscles in say a squat aren't firing so the knee comes in (the Valgus knee). That's not really a knee issue though, is it? That's poor form such that the person hasn't been taught to work a better squat pattern, or hasn't worked on what may be inhibiting a good squat movement? And so they're putting strain on their knees by failing to keep good position. Too much load, and absolutely perhaps issues in the ankle and hip and upper back that need to be addressed.

But i'm not really thinking about such a static movement as the squat. Really I'm thinking of the mighty number of girls who have ACL injuries in sports in the states these days. One theory (gathering momentum) has it that the girls who have ACL injuries showing up in basketball don't have a way to balance their increasingly higher (as going through puberty) center of balance. Intriguingly, the comments from the researchers is not to increase strength training (for more core or knee stability) but to increase their prorioceptive (body awareness) training.

The suggestion is not unlike studies on sensory-motor balance training with athletes to see if progressive balance work could help reduce ankle injury - another common problem for field and track athletes. They found that, effectively, progressively training for the sprain through this program helped the nervous system not go into panic, and predicted injuries would be less.

To take a lessen from martial arts as well where one practices for the fall pretty regularly, how much attention is given to working with an athlete on end range of motion work - not just balance work but what might be loaded balance work at the place where we rarely go in our training - that end range where recovery from a sudden lapse or accident is hard and where injuries occur? Is that augmenting mobility, stability or does it matter?

I go back to Boyle and Cook on the knees and back to their facesaying that these joints tend towards slopiness, and yet McGill (quoted by Boyle) saying no no, the low back in people with pain have stronger extensors than those without. So there's a lot of muscular strength around the low back already. The spine is *not* weak here (and by extension, one would say not sloppy if so much strength can be turned on?)

What's Going On? Where is this taking me? I'm hoping that Gray Cook's new book Movement will anser a lot of these queries. I'm looking forward to getting it, because right now the mobility/stability dialectic seems more problematic than helpful - at least to me. Here's why - and here's where i struggle with this as a model.

All the joints in the body have a pretty much well-scoped ranges of motion, right down to what the usual degres of movement are in each one. So why not simply be able to move all of these joints in these ranges of motion with strength and control as demanded by whatever that movement is - especially at the most vulnerable end ranges of motion?

Movement vs Mobility/Stability? Why not talk, therefore, just about "movement" (as Cook's book title suggests) rather than "mobility/stability." Is the question not really can one, for instance, hold a position for one particular movement or relax it for another? The knee needs not only to support the hinge with strength and power in say a basketball jump shot, but also needs to support the roll in with equal aplomb from standing to the ground - either when making a lunging tennis shot, or losing one's footing on a football pitch or simply getting pushed or in a fight getting from standing to knees to grapple quickly?