Showing posts with label 9S. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 9S. Show all posts

Saturday, August 14, 2010

A Model of an Athlete, of Athletecisim: z-health's 9s - also a model of coaching

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Here's a question that seems to be poking me on from the earlier "do we enjoy all our workouts/practices/training sessions?" And it's: What is our model of performance? what are the qualities to which we aspire in terms of living what i'm increasingly seeing as "embodied" lives - where we get that we're not just brains with bodies, but that our bodies are life enhancing? Before answering this, one might wonder why do we need a model? Why not just you know, keep moving? Eat well, rest well, move well.

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People demonstrates why

demonstrates why having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

having a framework informing what we do is part of being truly effective. For instance, he's well known for his expression rather than prioritise your schedule "schedule your priorities." In other words, make deliberate time for what is important. That's a principle. He calls it "put first things first" or suggests that "the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." To figure out what comes first, he has strategies to align with one's "true north" - one's principles. Come from principles first, not strategies like to-do lists or calendars. Those are tools; they are just the implementation details.

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great

In another now-foundational text about business success, Jim Collins and his team in Good to Great  attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

attempt to reverse engineer a set of principles that are in common with companies that made the leap from being Good companies to Great companies - companies that have beaten the market repeatedly for a particular period, by a particular percentage consecutively.

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First

and translate them into principles first and, following this, skills that can be practiced in line with these principles. For Covey, i'd suggest that the book First Things First  is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

is very much the workbook for the temporal organization part of the Seven Habits.

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

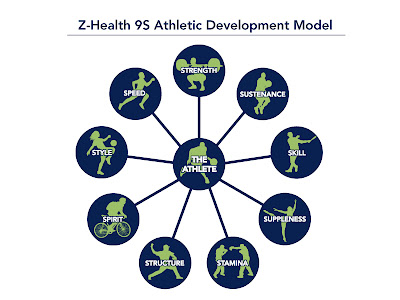

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

The cool thing i think is that stuff when we see someone great do it, we often take the approach of "wow, that person is really gifted - they just have that talent. what a gift" But a lot of that stuff can be taught. And practiced. With intent. We can develop skills. We can learn not only the tools to have to be a great coach, but how to BE a great coach.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated , and as Gladwell notes in Outliers

, and as Gladwell notes in Outliers , putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

, putting in the time to practice a skill is what separates the best from the rest. We need our ten thousand reps. But knowing the skills to rep, when, for how long - that's what makes a great coach, and how to be a great coach is no small thing. But a lot of it is skills too, and skills can be (a) taught and (b) practiced.

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Yup. That's great. For a certain quality of well. But what makes up that "wellness"? How do we understand that wellness so we can make decisions about what to include in our practice and what to discard; what's useful and what's for later, or not at all? Frameworks, models of a system, an organism can help. Indeed, these kinds of templates are usually more effective than specific programs. They usually relate to principles from which skills and pragmatics can be derived, progress or just needs assessed. And if we're actually in a place to coach someone, the value of such frameworks becomes even greater.

Let's consider what we mean by principle centered frameworks, consider the athlete in this, and take a look at the benefit of such an approach as a coaching model, too.

Principle Informed Frameworks - Models in Other Domains

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

We have examples of such adaptable models in other aspects of our way of being in the world. Steven Covey, author of the ubiquitously cited 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

Themes recur from attitudes of leaders to the way organizational management works. One of my favorite principles from the book is Get the Right People on the Bus. With the right folks, one can do almost anything, and thrive in any climate.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.

What's also interesting about the book is how many times Collins finds himself asking participants in the interviews about what their company's mission or vision is - and how this wasn't necessarily ever an explicit thing for people. The actions they took were not necesarily part of a pre-fabricated plan. It was just the right thing to do.The role of folks like Covey and Collins is to analyse the seeming instinctive behaviours of the Great

By developing skills practice, as in anything, skills are first paths towards accessing an action we want to accomplish - from a better tennis swing to a better email response practice (which may mean less email). Second, the repeated practice of a skill makes it a kind of habit or even reflex. That is we do it without having to think about it. It becomes engrained. For folks who constantly practice their skills, they become not just reflexive habits but stronger patterns. Talking with Steve Cotter the other day about a really nice GS snatch tutorial video he did, he was saying he had to do a new one because he was finding his technique was refining much faster now - months rather than years. Steve has been so focussed on his snatch technique and on teaching that technique in his IKFF for GS practice and competition, no kidding he's finding new performance refinements fast. It's amazing what having to teach does to thinking about breaking something into the most teachable units.

Model of the Athlete means Focus for Skills Development

Which brings us back to athletics from a principle driven model. So what is an athlete? or what are the attributes of athleticism? That's almost as bad as asking "what is motivation?" It's a skill too.

SO here's a model of an athlete that Eric Cobb put together and around which Z-Health (overview and index of related articles) is based.

|

| The Z-Health 9S model of the Athlete |

Strength, sustenance, skill, suppleness, stamina, structure, spirit, style and speed. All *equal sized* nodes on this graph. We all need strength: what kind of strength do we need in particular for what we do? Likewise suppleness. We all need to eat and recover. How tune that? How might one's structure be utilized or tuned to better support one's athletic goals? What about sports skills? How's one's physiological stamina mapped to one's ability to endure, to support, to be? to one's spirit? And what about one's own way of doing things, one's style? How support that to enhance rather than break one?

In graphing terms, this equal-node model is also a hub and spoke diagram where "the athlete is at the center" (the phrase you will here Cobb and Co. repeat often) and where everything is mediated through that center. This paradigm of the athlete as the mediating center of some core attributes takes coaching in an interesting direction, and situates Z-Health as a robust approach to training longevity that goes way beyond the foundation of movement drills.

I've written quite a bit about the principles from neuroscience that Z-Health translates as a kind of engineering of movement science or neuroscience into training practice. We've looked at Z-Health from dynamic joint mobility, to pain models, to threat modulation to CNS testing. the focus has been to improve movement quality and thereby to improve movement performance. These are the fundamental components of Z-Health. Moving limbs well, threat modulation for effective adapatation, these are the primary building blocks of the Z-Health approach as taught in the R,I,S and T certifications. But these fundamentals are themselves motivated by this overall model of the athlete, where the goal is how best support the athlete.

In other words, the goal of Z-Health as an approach is actually to use this model of the athlete (and in Z the starting point is "everyone is an athlete") as a principle-oriented, skills-based guide to coaching> The goal, as a coach, is to learn the skills - driven by the best practical, clinical and science lead research out there - to guide an athlete's performance on each of these parameters. Cobb talks about the best coaching is knowing when to emphasize which of these compnents in training, which then means knowing how emphasize the component, and within that, what content specifically to offer the athlete. That's non-trivial. That's serious stuff. Principles are serious. And the expectation is rather that as coaches we walk the walk not just talk the talk. I've said it before: everyone needs a coach. Do you have a coach who can talk with you about your speed and your swing and your sustenance? Why not? Here's a list of master trainers who really walk the walk.

Great Coaching - Practical Principled Coaching

for Deliverable, Repeatable, Skills-based Athleticism

We are wired to learn and to adapt - it's part of our survival mechanism.

Part of the approach of the 9S model is to break down components of practice into learnable skills. All of the movements in the basic drills of R and I phase are based on athletic movements (this is particularly apparent in I-Phase).

In the 9S courses, the emphasis is on getting at these larger components of athleticism and focusing on usable knowledge and practical skills, from nutrition to strength to speed to style, to make us better coaches, so that we have the depth and breadth to provide the right knowledge, the right tools, at the right time, within a pretty broad, holistic view of an athlete fundamentally as a person. As an example, last year in Sustenance and Spirit, we spent considerable time practicing coaching skills as drills. Active Listening anyone? This was really challenging work for a lot of us: how to listen and respond rather than just program and push. That was aside from the depth of detail we got into on basic nutrition, inflammation processes, supplement studies and related. Not just knowledge; not just tools but how to engage, when to deliver the right ones and the right time.

And sure there may be folks who are naturally gifted. But as Geoff Colvin notes in Talent is Overrated

There's an elegance to Cobb's model that i suspect as it becomes better known will end up plastered over strength coaches' walls. Sports programs will teach the 9S's as a way of communicating training goals and measurements. And what a day that will be.

It takes a certain kind of genius to ask the obvious questions and then find not only the non-trivial answers but the solutions that make them tractable, teachable, learnable while letting them still be wonderful. I think that likely Eric Cobb has done this with this approach to coaching, with the athlete-centred model of athleticism. Why? because it is principle centered, science based and skills-oriented. Each course, each cert is always geared to "what can you do with this monday morning when you're back with your athletes?"

Taking It Home.

This post started with a question about how do we guide our pursuit of embodied happiness, embodied well being? Having a model of what makes up success in a given domain seems to be a pretty good approach. Covey has such a model for engaging with others. Collins has a model for corporate progress. And i'd suggest Cobb (wow, another C) has a model for athletic well being. And since we all have bodies and move, well, everyone is an athlete.

So if you've been riffing on Z-Health as a great approach to movement, and feeling better, maybe moving out of pain or into better performance having seen a Z-Health coach, that's great. It is super fantastic for this. If you're interested in getting started with Z-Health, here's a big fat Z-Health overview.

If you're thinking about an approach to training, about learning skills to train better, and about getting at the science of movement and these 9S's in an intelligent, useful and usable way, Z-Health is really reaching to get folks there. And that's kind of a new paradigm too for fitness, strength and conditioning, and sports-oriented training. Kinda makes me go hmm. This is an interesting place to be, and i'm inclined to watch this space. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

9S,

coach,

principles,

z-health,

zhealth

Monday, July 20, 2009

What the Heck is Sustenance? Review of the Z-Health 9S Course on Sustenance and Spirit

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

This was the questions a colleague instant messaged me when i got back from the Z-Health 9S Sustenance course "what the heck is Sustenance". There's a lot to unpack in both the very reasonable question and the highly compressed title. So the following is a review/overview of the Z-Health 9S: Sustenance Certification Course (for the full moniker). We'll come back to what the heck 9s means at some other point. I digress.

Let me start with the definition that was on the Z-Health site 9S certification series page:

Indeed, while on the one hand 5 days sounds like an intense course, no one would seriously believe that one could teach a complete course about nutrition in terms of even what certifications like the NSCA CSCS teach about energy systems, metabolism and so on (by way of example, here's an attempt to overview something of fat metabolism). There's just TOO MUCH at that level of detail. And how practical is it for dealing with folks who want to do better with their health?

So really, what can be delivered in 5 days such that at the end of it, a trainer would feel they have something of value that they didn't have before? What's this connection "between nutrition and the principles of Z-Health"?

Threat Modulation: It's a Neural Thing. Z-Health is grounded in a neural approach to just about everything. The fundamental focus on the neural system is that it signals "danger/threat" or "no danger / no threat". Based on this, Z-Health is about "threat modulation." Better movement as taught in R-Phase, I-Phase and S-Phase, means reduced threat. I've detailed how movement means threat reduction previously, for instance, as described in this piece on I-Phase - the key takeaway is we can train for the sprain.

the neural system is that it signals "danger/threat" or "no danger / no threat". Based on this, Z-Health is about "threat modulation." Better movement as taught in R-Phase, I-Phase and S-Phase, means reduced threat. I've detailed how movement means threat reduction previously, for instance, as described in this piece on I-Phase - the key takeaway is we can train for the sprain.

Suffice it to say here that better movement means both more and clearer signals sent to the brain about where the body is in space; with both the improved ability to move the body into more positions, more precisely, the body has a far greater range of options with which to respond to perceived threats. So that means (a) dealing with threat when it arises more quickly and effectively and (b) simply being able to spend more time out of threat.

ASIDE: Threat may sound like a really big thing and you might not sense yourself in a sense of threat on a regular basis. Our low level systems just may. To get a sense of how subtly this happens but how quickly it can take place, check out this vid of the "arthrokinetic reflex"

When taken from a Z-Health perspective that every neural process that gets to the brain is framed by the brain - whether that's an action signal from a neural process being interpreted as pain, or one interpreted as hunger - having strategies to address these signals is a Good Idea.

In the main Z-Health courses, we talk about the Nerual Matrix (based on Melzack '68) for pain. In 9S:Sustenance, we considered the neural matrix analogue for hunger. Pain/hunger: both can be signs signaling an urgency demanding a response from us.

So if we accept that threat modulation is a good idea - the less threatened the body feels the more freely and effectively it can move and engage in the world; and that hunger/pain are both signals requiring attention to get back to that de-threatened state of well-being - then a Z-Health connection to food, eating, nutrition becomes starts to emerge: how identify and address those threat-type signals around food?

One of the biggest reasons people (over)eat, for instance, is related to stress, or feeling overwhelmed or under attack. Eating is tied up with us, then, not only in terms of chemical signals that say we're hungy or not, we need carbs or we need fats (and yes it turns out we really do have signals that are that specific), but with habituated responses to these signals; they reinforce each other chemically, and where in our earlier days when food was not as abundantly available as it is now, those chemical signals did us a lot of good. Stress is about survival: go get food. Those signals kept us alive.

Our responses to stress in terms of being equated with looking for fuel have not kept pace with our environmental evolution. So, just as we have to do things like Z-Health mobility work and exercise to keep us mobile and our system limber in a largely, but not entirely, sedentary world, we need now to learn new approaches to eating to align ourselves better with our new, affluent, food-abundant circumstances.

So this particular course Sustenance/Spirit focused on what its designer Eric Cobb calls the 20% solution, based on the 80/20 rule: what's the 20% big bang from all of what could be covered about nutrition that will yield at least 80% on results?

To that end, 9S:sustenance focuses on some basics:

Sustenance: to sustain, to provide for the spirit; to support from below. Thus, sustenance is to provide the platform for a person to begin to sustain themselves effectively for their health and well being. So what of nutrition and coaching would be potent to know in order to help sustain a client?

Where are the pain points in diet today? - Last week, in "mc's Change One Thing Only diet" over at iamgeekfit, i highlighted some of the simple stats that show how simple pervasive practices are at the forefront of weight problems. For example the amount of calories consumed while driving, from pop/juice, while watching TV, etc, all easily mean if just one of these were mediated, there'd be huge effects. We looked at food availability and how portion size has changed over the past 20 years (see examples and refs towards the end of this article), and where these sublte, hidden, progressive changes have impacted - and continue to impact - our consumption of cheap fuel practices. The challenge is, of course, mediating just one thing sounds so simple. So why isn't it? What's going on where, and how address that so that such changes are possible?

Macro Nutrient Ratios - second order focus. We looked at research overviews on types of diets whether zone, atkins, paleo, etc, and how they all come down to the same thing for weight loss: caloric reduction. Over time the only constant in any diet working is caloric restriction. Over time the only thing that keeps working is persistence. Fewer calories in than out means weight reduction/fat loss. It's that simple. Not easy, but simple.

Exercise - second order focus. We looked at the research that it doesn't matter how much you exercise: weight loss happens with caloric restriction (that's been a theme at b2d; nice to see it reiterated here). Indeed, Mike T Nelson lead a couple cool sections on "metabolic flexibility" - and how well we adapt to getting energy from fat and carbs - we are highly adaptable. But for a room full of athletic people whose primary mission is to help people to move, this is a key fact, now proven in numerous studies: we can't outrun a donut. Or sadly my fave toast and cheese is equivalent to one killer interval session. Dang.

Blood Work - where does it fit in? We looked at blood work - not so that we could do an analysis of it for our clients - we ain't licensed to do that - but to understand what's in blood work if our clients bring it in or begin to quote from previous tests. That was really cool.

I personally learned quite quickly how blood work is not representative of athletic populations: my numbers on two markers mean that i'm about to die of kidney failure. Oh wait - not if i'm "muscular" or "taking creatine" - does the lab work reference point to these exceptions? Nooo. Had to tool around the web a LOT to find them.

This wee look at my own numbers also reinforced why obsessing over a single number from a single test- or trying to diagnose anyone's condition from such a single data point - mayn't be a good idea : when i pointed out that the diagnosis from this result was dire and that i should consider dialysis soon, i was told by a medico there "there'd be other symptoms if that were the case."

Eating - homeostatic and hedonic signals. Why we eat, what we eat, when we eat, how we eat, where we eat - is Complex. It's not single factor. So we looked at some of the drivers for eating: we looked at hunger. We looked at it from a high-level phys-chem set of homeostatic signals and we looked at it from a set of associated responses that get wrapped up around those signals. We also looked at it from the highly complex issue of what constitutes satiety. Who'd a thunk that satiety would be a HUGE issue. It is so much more than feeling full. Though that's part of it. Sometimes.

Inflamation. We also looked at a very fundamental view of some very basic concepts around inflammation and the role of diet. This section was particularly important for achieving a better understanding what's going on with insulin, with anti-oxidants, and what's up with the omega 9,6 and 3 fats that are all the rage.

No one would claim from this course that they left experts on inflammation (unless they were going into it as an area of study - but after this course, it's clear anyone who would make such a general claim is likely not a straight shooter).

But in a way that's part of the cool thing from the course itself: this stuff - how we process fuel, movement, our environment, and so on - is so complex that to think we can say something as simple as "take vitamin C" or "don't take vitamin C" and you'll be healthy is way way way far away from The Real. And inflammation is just not something i had thought as having such a constant, critical effect on our systems. It's HUGE. And diet/movement/lifestyle are HUGE players in how our system mediates inflammatory responses. Oh wow. And complex. But suffice it to say, how, what, where, when we eat is a big deal with respect to inflammation. Again, fortunately for us, while the systems are incredibly complex, the principles to optimize their performance are shown over and over again to be simple. Hard, it seems, for us to get them dialed in, but simple.

By getting a sense of this complexity from the course, to see some of the pathways informing the critical concepts that do come up all the time in popular discourse about nutrition, is to get sensitized to a heightened appreciation of why we just cannot say unequivocally most of the time, do x and get y.

The Big Take Away from the course, from the above tour through complexity was an eye-opener. It was framed as Single Factor Thinking and how much as a culture we practice Single Factor THinking, desire Single Factor Answers and how unrealistic this approach is with systems as complex and elegant as our own.

Single Factor Thinking is based on the scientific experiment that simply wants to test if we change this Single Thing and hold everything else constant, will we get the effect that we want? A simple example is we have water in a glass. If the only thing we change is the temperature of the water, will we change its solidity one we hit 0C. We don't change the size of the glass, the amount of water, what's in the water. Nothing. Just the temperature. Easy. Single Change to see if there is a single, predicted effect. Imagine if the water didn't freeze at that temperature: all the things we'd have to check to see what was wrong before we could say 0C is not the temp water freezes at? The thermometer, the mechanism for freezing, and possibly the water itself to make sure that the sample has no saline or other particles that would effect the freezing point. And that's just for something as simple as freezing water in a well controlled single factor study.

Imagine how the complexity of control increases when dealing with human systems. First, when dealing with human systems it's really hard to get such total control over what participants do and are like that to be able to say with certainty that a study's intervention lead to that result. It can be done with a high degree of statistical certainty, but has to be really carefully set up (read: expensive and therefore costly to repeat). Second, that kind of control is so far from reality that ya have to ask, ok, will that effect still hold when all the other usual factors are thrown back in? And Third, what happens if you can say yes we have a clear X that does Y but in doing Y do we get this horrible undesirable Z, too?

Single Factor Thinking, Redux. Despite all these problems with the complexity of science and the reluctance of scientists consequently to generalize their results to claim that based on their one study these results will apply to everyone, we still tend to want exactly that, and our marketing machines certainly promise that: do this one exercise and be svelt in 12 weeks; take this one pill and shed your fat, and so on. The media is similarly attracted to framing science in simple soundbites: Vitamins are evil; vitamins are great.

The message the 9S course kept bringing home is that Single Factor Thinking is Not Viable when it comes to nutrition in general, or the more particular issue of dealing the obesity epidemic on one end to humble "fat loss" of a few pounds on the other. Whether that's looking at one thing in someone's diet or one thing in their blood work or one any one thing.

Getting Real

Diets. We did learn too some really solid basics around kick starting diets, getting some positive support, and being able to succeed. We talked about frequent feeding vs Intermittent Fasting vs Zero Grains etc. I've become a lot more diet-agnostic as a result of this course. What works for the individual in the context of all these other homeostatic and hedonic, habitual processes? That's where the mc's Change One Thing first step diet i posted last week comes from: acknowledge the habits, and get a plan to deal with 'em, one safe, low threat way at a time.

Supplements. We talked about supplements too: about what, based on lots of research and clinical practice are the ones sufficiently shown to be of benefit that they're worth having in one's cupboard.

Perhaps the more critical component of this issue is once identifying the good stuff, who do you trust to supply it? Who checks? Since 1994 when the FDA was taken out of the supplement tracking business, there's no standardization. Consistency - where a pill may have some to none of what the label claims - is a real problem. Dam. How does knowing this affect a generic recommendation to "get some vitamin D" (a good thing)? (update: overview of the supplement certification systems)

Habit Mashing. Big take away again: there is no The One Reason we do This Eating Thing. The best way, however, it seems that we have to address the multiple physiological, neurological, biological, things going on around food, is to get at the complexity of behaviours associated with these very old, very survival based multiplicity of triggers that drive us to ReFuel.

The behavioural approach is not new. In fact there are at least three Big How To Diet Books (as opposed to diet books) out right now that take advantage of this, all worth looking at, and all part of the course preliminary reading (discussed in more detail here). What one of the things this certification offered that i think is pretty unique is a far deeper physiologic rationale for *why* the behaviour approach is such a good one as opposed to a more macronutrient approach first. For instance, if someone eats a lot of carbs in the car, drinks pop, eats in front of the tv and gets crappy sleep - and this is a regular practice - how successful will saying "here's this paleo diet - just do this and you'll be fine."

Aside: it's the habit-based approach to precision nutrition that has had me a fan for a long time: the subtlety of the 9S course is that creating new habits, even good ones (duh) is a Big Deal, so how help folks get there who maybe aren't ready to take the plunge? are still sitting on the fence? How help coach this new practice? and how integrate nutrition into the rest of a client's life if one is coming to us for say pain relief or movement work?

Coaching is to Listen and Guide rather than Direct. To that end we spent a whole lot of time on concepts and exercises grounded in Motivational Interviewing and related work to be able to listen to folks, help understand if they want to do nutrition work with what else they are doing, are they ready, how to help them move to being ready, and once they are, how to facilitate that readiness.

One of the most valuable pieces of the course, drawing on the transtheoretical model in psychology and from cognitive behavioural therapy is that not everyone is ready to make a change, and being able to get quickly where someone is at

Overview "the key to progress is to begin by telling the truth."

Maybe from this brief overview of the 9S sustenance course, you can get the sense of how this certification would have succeeded on delivering that 20% solution for helping folks with exploring solutions for their hunger/eating issues and on to the path to "good nutrition." And thus, likewise, where folks with this certification may be somewhat different in their own approach in working with others on nutrition as part of a holistic approach to quality of life to someone who begins a session with "right, let's see a food log of what you've eaten for the last three days."

It's certainly helped me, who's been into reading nutrition studies quite a bit, not to leap at Mike in our Minute with Mike Series, when he said eh, not much difference with Whey, BCAA's and Leucine - Whey's likely better. :) THough i did have to restrain myself on the post workout recovery window.

We know that we all misrepresent that kind of self-reporting information. Is that starting with "telling the truth"? If that were working for us, would there be an eating/overweight crisis in the western world, and now China? How's that been working for us?

So Sustenance looks at other truths we might be able to help folks (and ourselves) assess: what do we really think about our approach to health and eating ? what do we really want to achieve? do we know? are we on the fence? how can we help understand where to come down, off which side? and then what?

The interdisicplinary approach to the material is a profound approach. As in all Z-Health courses, the key was the way the what stuff was broken down into skill chunks that we can use immediately in our practice working with folks.

If you know someone looking for help in getting one with their eating, think about connecting them with someone who's taken this course. Ya sure i'm biased, but i hope from the above it's clear why :)

Shout if you have questions. Thanks for reading. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Let me start with the definition that was on the Z-Health site 9S certification series page:

9S: Sustenance explores the connections between nutrition and the principles of Z-Health Performance. The course focuses on using accurate, repeatable nutritional evaluation techniques, as well as the development of exceptional coaching and motivational skills to assist clients in making the required lifestyle changes that promote permanent changes in health, fitness, performance and body composition.From that definition, one can see that while this was most often discussed among trainers as "the Z-Health advanced nutrition course," the curriculum is a lot broader and one might say deeper than covering one of the laws of thermodynamics (conservation of energy or, cals in = cals out).

Indeed, while on the one hand 5 days sounds like an intense course, no one would seriously believe that one could teach a complete course about nutrition in terms of even what certifications like the NSCA CSCS teach about energy systems, metabolism and so on (by way of example, here's an attempt to overview something of fat metabolism). There's just TOO MUCH at that level of detail. And how practical is it for dealing with folks who want to do better with their health?

So really, what can be delivered in 5 days such that at the end of it, a trainer would feel they have something of value that they didn't have before? What's this connection "between nutrition and the principles of Z-Health"?

Threat Modulation: It's a Neural Thing. Z-Health is grounded in a neural approach to just about everything. The fundamental focus on

the neural system is that it signals "danger/threat" or "no danger / no threat". Based on this, Z-Health is about "threat modulation." Better movement as taught in R-Phase, I-Phase and S-Phase, means reduced threat. I've detailed how movement means threat reduction previously, for instance, as described in this piece on I-Phase - the key takeaway is we can train for the sprain.

the neural system is that it signals "danger/threat" or "no danger / no threat". Based on this, Z-Health is about "threat modulation." Better movement as taught in R-Phase, I-Phase and S-Phase, means reduced threat. I've detailed how movement means threat reduction previously, for instance, as described in this piece on I-Phase - the key takeaway is we can train for the sprain.Suffice it to say here that better movement means both more and clearer signals sent to the brain about where the body is in space; with both the improved ability to move the body into more positions, more precisely, the body has a far greater range of options with which to respond to perceived threats. So that means (a) dealing with threat when it arises more quickly and effectively and (b) simply being able to spend more time out of threat.

ASIDE: Threat may sound like a really big thing and you might not sense yourself in a sense of threat on a regular basis. Our low level systems just may. To get a sense of how subtly this happens but how quickly it can take place, check out this vid of the "arthrokinetic reflex"

When taken from a Z-Health perspective that every neural process that gets to the brain is framed by the brain - whether that's an action signal from a neural process being interpreted as pain, or one interpreted as hunger - having strategies to address these signals is a Good Idea.

In the main Z-Health courses, we talk about the Nerual Matrix (based on Melzack '68) for pain. In 9S:Sustenance, we considered the neural matrix analogue for hunger. Pain/hunger: both can be signs signaling an urgency demanding a response from us.

So if we accept that threat modulation is a good idea - the less threatened the body feels the more freely and effectively it can move and engage in the world; and that hunger/pain are both signals requiring attention to get back to that de-threatened state of well-being - then a Z-Health connection to food, eating, nutrition becomes starts to emerge: how identify and address those threat-type signals around food?

One of the biggest reasons people (over)eat, for instance, is related to stress, or feeling overwhelmed or under attack. Eating is tied up with us, then, not only in terms of chemical signals that say we're hungy or not, we need carbs or we need fats (and yes it turns out we really do have signals that are that specific), but with habituated responses to these signals; they reinforce each other chemically, and where in our earlier days when food was not as abundantly available as it is now, those chemical signals did us a lot of good. Stress is about survival: go get food. Those signals kept us alive.

Our responses to stress in terms of being equated with looking for fuel have not kept pace with our environmental evolution. So, just as we have to do things like Z-Health mobility work and exercise to keep us mobile and our system limber in a largely, but not entirely, sedentary world, we need now to learn new approaches to eating to align ourselves better with our new, affluent, food-abundant circumstances.

So this particular course Sustenance/Spirit focused on what its designer Eric Cobb calls the 20% solution, based on the 80/20 rule: what's the 20% big bang from all of what could be covered about nutrition that will yield at least 80% on results?

Make it as simple as possible, but not simpler

- Einstein (quotation from the course)

- Einstein (quotation from the course)

To that end, 9S:sustenance focuses on some basics:

Sustenance: to sustain, to provide for the spirit; to support from below. Thus, sustenance is to provide the platform for a person to begin to sustain themselves effectively for their health and well being. So what of nutrition and coaching would be potent to know in order to help sustain a client?

Where are the pain points in diet today? - Last week, in "mc's Change One Thing Only diet" over at iamgeekfit, i highlighted some of the simple stats that show how simple pervasive practices are at the forefront of weight problems. For example the amount of calories consumed while driving, from pop/juice, while watching TV, etc, all easily mean if just one of these were mediated, there'd be huge effects. We looked at food availability and how portion size has changed over the past 20 years (see examples and refs towards the end of this article), and where these sublte, hidden, progressive changes have impacted - and continue to impact - our consumption of cheap fuel practices. The challenge is, of course, mediating just one thing sounds so simple. So why isn't it? What's going on where, and how address that so that such changes are possible?

Macro Nutrient Ratios - second order focus. We looked at research overviews on types of diets whether zone, atkins, paleo, etc, and how they all come down to the same thing for weight loss: caloric reduction. Over time the only constant in any diet working is caloric restriction. Over time the only thing that keeps working is persistence. Fewer calories in than out means weight reduction/fat loss. It's that simple. Not easy, but simple.

Exercise - second order focus. We looked at the research that it doesn't matter how much you exercise: weight loss happens with caloric restriction (that's been a theme at b2d; nice to see it reiterated here). Indeed, Mike T Nelson lead a couple cool sections on "metabolic flexibility" - and how well we adapt to getting energy from fat and carbs - we are highly adaptable. But for a room full of athletic people whose primary mission is to help people to move, this is a key fact, now proven in numerous studies: we can't outrun a donut. Or sadly my fave toast and cheese is equivalent to one killer interval session. Dang.

Blood Work - where does it fit in? We looked at blood work - not so that we could do an analysis of it for our clients - we ain't licensed to do that - but to understand what's in blood work if our clients bring it in or begin to quote from previous tests. That was really cool.

I personally learned quite quickly how blood work is not representative of athletic populations: my numbers on two markers mean that i'm about to die of kidney failure. Oh wait - not if i'm "muscular" or "taking creatine" - does the lab work reference point to these exceptions? Nooo. Had to tool around the web a LOT to find them.

This wee look at my own numbers also reinforced why obsessing over a single number from a single test- or trying to diagnose anyone's condition from such a single data point - mayn't be a good idea : when i pointed out that the diagnosis from this result was dire and that i should consider dialysis soon, i was told by a medico there "there'd be other symptoms if that were the case."

Eating - homeostatic and hedonic signals. Why we eat, what we eat, when we eat, how we eat, where we eat - is Complex. It's not single factor. So we looked at some of the drivers for eating: we looked at hunger. We looked at it from a high-level phys-chem set of homeostatic signals and we looked at it from a set of associated responses that get wrapped up around those signals. We also looked at it from the highly complex issue of what constitutes satiety. Who'd a thunk that satiety would be a HUGE issue. It is so much more than feeling full. Though that's part of it. Sometimes.

Inflamation. We also looked at a very fundamental view of some very basic concepts around inflammation and the role of diet. This section was particularly important for achieving a better understanding what's going on with insulin, with anti-oxidants, and what's up with the omega 9,6 and 3 fats that are all the rage.

No one would claim from this course that they left experts on inflammation (unless they were going into it as an area of study - but after this course, it's clear anyone who would make such a general claim is likely not a straight shooter).

But in a way that's part of the cool thing from the course itself: this stuff - how we process fuel, movement, our environment, and so on - is so complex that to think we can say something as simple as "take vitamin C" or "don't take vitamin C" and you'll be healthy is way way way far away from The Real. And inflammation is just not something i had thought as having such a constant, critical effect on our systems. It's HUGE. And diet/movement/lifestyle are HUGE players in how our system mediates inflammatory responses. Oh wow. And complex. But suffice it to say, how, what, where, when we eat is a big deal with respect to inflammation. Again, fortunately for us, while the systems are incredibly complex, the principles to optimize their performance are shown over and over again to be simple. Hard, it seems, for us to get them dialed in, but simple.

By getting a sense of this complexity from the course, to see some of the pathways informing the critical concepts that do come up all the time in popular discourse about nutrition, is to get sensitized to a heightened appreciation of why we just cannot say unequivocally most of the time, do x and get y.

map of metabolic processes. can you find the Krebs cycle?

The Big Take Away from the course, from the above tour through complexity was an eye-opener. It was framed as Single Factor Thinking and how much as a culture we practice Single Factor THinking, desire Single Factor Answers and how unrealistic this approach is with systems as complex and elegant as our own.

Single Factor Thinking is based on the scientific experiment that simply wants to test if we change this Single Thing and hold everything else constant, will we get the effect that we want? A simple example is we have water in a glass. If the only thing we change is the temperature of the water, will we change its solidity one we hit 0C. We don't change the size of the glass, the amount of water, what's in the water. Nothing. Just the temperature. Easy. Single Change to see if there is a single, predicted effect. Imagine if the water didn't freeze at that temperature: all the things we'd have to check to see what was wrong before we could say 0C is not the temp water freezes at? The thermometer, the mechanism for freezing, and possibly the water itself to make sure that the sample has no saline or other particles that would effect the freezing point. And that's just for something as simple as freezing water in a well controlled single factor study.

Imagine how the complexity of control increases when dealing with human systems. First, when dealing with human systems it's really hard to get such total control over what participants do and are like that to be able to say with certainty that a study's intervention lead to that result. It can be done with a high degree of statistical certainty, but has to be really carefully set up (read: expensive and therefore costly to repeat). Second, that kind of control is so far from reality that ya have to ask, ok, will that effect still hold when all the other usual factors are thrown back in? And Third, what happens if you can say yes we have a clear X that does Y but in doing Y do we get this horrible undesirable Z, too?

Single Factor Thinking, Redux. Despite all these problems with the complexity of science and the reluctance of scientists consequently to generalize their results to claim that based on their one study these results will apply to everyone, we still tend to want exactly that, and our marketing machines certainly promise that: do this one exercise and be svelt in 12 weeks; take this one pill and shed your fat, and so on. The media is similarly attracted to framing science in simple soundbites: Vitamins are evil; vitamins are great.

The message the 9S course kept bringing home is that Single Factor Thinking is Not Viable when it comes to nutrition in general, or the more particular issue of dealing the obesity epidemic on one end to humble "fat loss" of a few pounds on the other. Whether that's looking at one thing in someone's diet or one thing in their blood work or one any one thing.

Getting Real

Diets. We did learn too some really solid basics around kick starting diets, getting some positive support, and being able to succeed. We talked about frequent feeding vs Intermittent Fasting vs Zero Grains etc. I've become a lot more diet-agnostic as a result of this course. What works for the individual in the context of all these other homeostatic and hedonic, habitual processes? That's where the mc's Change One Thing first step diet i posted last week comes from: acknowledge the habits, and get a plan to deal with 'em, one safe, low threat way at a time.

Supplements. We talked about supplements too: about what, based on lots of research and clinical practice are the ones sufficiently shown to be of benefit that they're worth having in one's cupboard.

Perhaps the more critical component of this issue is once identifying the good stuff, who do you trust to supply it? Who checks? Since 1994 when the FDA was taken out of the supplement tracking business, there's no standardization. Consistency - where a pill may have some to none of what the label claims - is a real problem. Dam. How does knowing this affect a generic recommendation to "get some vitamin D" (a good thing)? (update: overview of the supplement certification systems)

Habit Mashing. Big take away again: there is no The One Reason we do This Eating Thing. The best way, however, it seems that we have to address the multiple physiological, neurological, biological, things going on around food, is to get at the complexity of behaviours associated with these very old, very survival based multiplicity of triggers that drive us to ReFuel.

The behavioural approach is not new. In fact there are at least three Big How To Diet Books (as opposed to diet books) out right now that take advantage of this, all worth looking at, and all part of the course preliminary reading (discussed in more detail here). What one of the things this certification offered that i think is pretty unique is a far deeper physiologic rationale for *why* the behaviour approach is such a good one as opposed to a more macronutrient approach first. For instance, if someone eats a lot of carbs in the car, drinks pop, eats in front of the tv and gets crappy sleep - and this is a regular practice - how successful will saying "here's this paleo diet - just do this and you'll be fine."

Aside: it's the habit-based approach to precision nutrition that has had me a fan for a long time: the subtlety of the 9S course is that creating new habits, even good ones (duh) is a Big Deal, so how help folks get there who maybe aren't ready to take the plunge? are still sitting on the fence? How help coach this new practice? and how integrate nutrition into the rest of a client's life if one is coming to us for say pain relief or movement work?

Coaching is to Listen and Guide rather than Direct. To that end we spent a whole lot of time on concepts and exercises grounded in Motivational Interviewing and related work to be able to listen to folks, help understand if they want to do nutrition work with what else they are doing, are they ready, how to help them move to being ready, and once they are, how to facilitate that readiness.

Communication is not about what you said; it's about what's heard.

One of the most valuable pieces of the course, drawing on the transtheoretical model in psychology and from cognitive behavioural therapy is that not everyone is ready to make a change, and being able to get quickly where someone is at

Overview "the key to progress is to begin by telling the truth."

Maybe from this brief overview of the 9S sustenance course, you can get the sense of how this certification would have succeeded on delivering that 20% solution for helping folks with exploring solutions for their hunger/eating issues and on to the path to "good nutrition." And thus, likewise, where folks with this certification may be somewhat different in their own approach in working with others on nutrition as part of a holistic approach to quality of life to someone who begins a session with "right, let's see a food log of what you've eaten for the last three days."

It's certainly helped me, who's been into reading nutrition studies quite a bit, not to leap at Mike in our Minute with Mike Series, when he said eh, not much difference with Whey, BCAA's and Leucine - Whey's likely better. :) THough i did have to restrain myself on the post workout recovery window.

We know that we all misrepresent that kind of self-reporting information. Is that starting with "telling the truth"? If that were working for us, would there be an eating/overweight crisis in the western world, and now China? How's that been working for us?

So Sustenance looks at other truths we might be able to help folks (and ourselves) assess: what do we really think about our approach to health and eating ? what do we really want to achieve? do we know? are we on the fence? how can we help understand where to come down, off which side? and then what?

The interdisicplinary approach to the material is a profound approach. As in all Z-Health courses, the key was the way the what stuff was broken down into skill chunks that we can use immediately in our practice working with folks.

If you know someone looking for help in getting one with their eating, think about connecting them with someone who's taken this course. Ya sure i'm biased, but i hope from the above it's clear why :)

Shout if you have questions. Thanks for reading. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

9S,

9S:Sustenance,

nutrition,

z-health

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

COACHING with dr. m.c.

COACHING with dr. m.c.