Showing posts with label shoulder. Show all posts

Showing posts with label shoulder. Show all posts

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Unpacking a mystery: when shoulder pain may be all (or largely) in the wrist (a t-phase assessment story)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Pavel tells the joke about asking people in a weight room "so those of you who have had a shoulder injury, raise your hands" - half the people raise their hands; the other half can't.

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

mc

Related Posts

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

1) pain in the biceps: there's that biceps tendon going into the shoulder - address that, and guess what - pain HUGELY reduced.

2) help out the brachioradialis/extensors (esp carpi radialis perhaps) overlapping tendon/musle area, there's more relief (nerve work for the radial nerve included).

3) muscle test some of those extensors and there's squishy bits - get that fixed so the whole extensor is firing, more relief.

4) pay attention to the axilary nerve that fires the deltoids, and the posterior delt starts to come back on line (have some more work to do there but heck it's work i know how to do).

5) do a wee bit of hybrid minimal t-phase style kinesio taping around the long head bicpes tendon area, matched up with active dynamic joint mobility drills for the shoulder, elbow and extensors, and things start to simmer down

6) work out some of the fascial stickiness around the extenors with v.light hybrid t-phase fascial work

7) get some exercises for working the extensors in particular,

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

Personal Practice So suggestion? If you're having hinky performance/pain issues, check in with a movement performance specialist. Here's a trainer listing. If you'd like a referal, call the office, and let them know mc suggested you ask them.Best with your practice,

mc

Related Posts

- Tendinopathy, tendinitis and Eccentric Exercise for rehab

- Ensuring that the *whole* muscle fires in a movement for real strength

- Why not move through pain

- dealing with chronic back pain

- active vs passive care/therapy

Monday, June 21, 2010

The amazing shoulder - part 2: glenohumeral joint & muscles (yes rotator cuff too)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

In part one of this quick tour of the amazing shoulder we looked particularly at the shoulder girdle and the muscles that act pretty much directly on the scapula. The main take away was that significant muscles like the traps, rhomboids, pec minor, serratus anterior and levator scapula all work pretty much *just* to move the scapula and so reposition the shoulder joint socket to extend range of motion for the arm moving in the shoulder.

In this piece, we'll overview those pixie rotator cuff muscles and look at why they can be such a pain - in the shoulder - and how understanding the movements these muscles support may help reduce injury risk.

We'll also take a quick look at the big muscles like the lats that opperate on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumral joint. From here we'll speculate about shoulder injuries and habits to avoid them.

The shoulder tour part II: The Glenohumeral Action

Rotator Cuff What is it with the rotator cuff? we hear about so many injuries to the shoulder, and we likewise hear so much about the need to "prehab" these muscles to defeat injury. And i'm not a bystander here: i've likewise run my shoulder into the wall and shook my head to say "what is this pain? what is this thing? what needs to change? what the heck is wrong here?" I've had folks say "ah, that's the supraspinatus most like" -Um, could you unpack that a bit? No? ok. So here's a go at trying to get a little better understanding of a bit of what's happening with the rotator cuff.

First, the GlenoHumeral Joint. In moving to the rotator cuff, we're moving away from a focus on the shoulder girdle and the movement of the scapula to the main reason for the scapula: the gleno-humeral connection - or connecting the extremity that is the arm to the trunk of the body - the upper body in particular.

Where that connection takes place is with the humeral head of the humerous being knit into the glenoid cavity (or fossa) of the scapula. Note again the side view of the scapula - the glenoid fossa is rather shallow, but there's a liner/washer called the glenoid labrum that gets inset into that cavity before the humeral head makes contact. And then there's a capsule that goes around that unit, and ligaments around that. Those ligaments are kind of like a snugly-but-loosely laced sneakers - there's some give because of all the range of motion in the shoulder. This looseness - it's a bug; it's a feature.

Rotator Cuff Job 1 - holding ball in socket.

Just for context, there are four rotator cuff muscles: 1 on top, the SUPRAspinatus, 1 covering the front that goes against the underside of the scapula that is against the ribs the SUBscapularis, and two on the back of the scapula, the infraspinatus and and the teres minor

The top muscle, the supraspinatus (supra=above the spiney bit), attaches from the top of the scapula at the big scapula spine, runs along the top of that ridge, goes under the acromium process of the scapular spine, over the bursa on the top of the glenohumeral capsule and then attaches onto a big bump at the top of the humerus, the greater tubercle. That is a very popular attachment point - like the superior spine of the scapula but much smaller a peak. So when this muscle contracts, it's going to help pull the arm up to 90 degrees from one's side - called abduction. Note i say "help" - we'll come back to this assistance role. Mainly it's stabilizing the ball of the humerus in the glenoid socket.

The subscapularis which attaches along the entire scapula underside (the scapula fossa) the attaches around the front of the humerus at the lesser tubercle. If you imagine these fibers contracting, they're going to contribute to turning the humerus in (internal rotation), pulling the humerus across the body, pulling the arm back (into extension) and, of course 'stabilizing the humeral head in the glenoid fosa' - as the manual of structural kinesiology puts it.

puts it.

The infraspinatus is the complement to the subscapularis: subscapularis = under(side) of the scapula; infraspinatus means below the spiney bit. Names are nicely descriptive. Where the subscapularis covers the underside of the scapula, the infraspinatus covers the whole backside of the scapula below that big scapular spine. Where the supraspinatus attaches to the top of the greater tubercle, the infraspinatus attaches to the back of the greater tubercle. So again, if we imagine pulling / contracting that attachment, the kinds of things that can happen to the arm are - its turned out (externally rotated), it's also going to pull the arm back into extension. It also helps with what's known as horizontal abduction. Big role - stabilize the arm in the socket - we might add especially when it's being moved about.

The teres minor is like a support for the infraspinatus. Teres just means round and smooth (cylyndrical). and that's sort of what this muscle is. It hangs onto the lateral border of the scapula (the edge closer to the arm), and then plugs in under the greater tubercle of the humerus. So what's it going to do? Exactly the same as the infraspinatus: *stabilization,*external rotation, extension and horizontal abduction.

Note: horizontal abduction is different from abduction: abduction, the arm is being raised up at the side; horizontal abduction assumes that the arm is already up at ninety degrees and infront of the body, and so the arm is being pulled back (abduction - ab is latin for from, as in away from rather that ad, to, towards).

Summary of RCM Action That's it: 4 muscles with pretty functionally descriptive names.

They all have four things in common:

They're so WEAK, what's the point of being muscles?

In reading kinesiology texts, a word repeated all the time about the rotator cuff muscles is "weak" - they provide weak adduction, weak abduction, weak rotation - weak weak weak. no leverage. like a person trying to open a door when the handle is in the middle of the door.

If they're so weak what are they doing there? One of the best reframings of the roll of the RCMs is in the Anatomy of Movement . There Calais-Germain uses the term "active ligaments" to describe the function of these muscles. Considering that it's the tendon part of the muscles that usually comes to grief when we talk about overuse injuries or RC problems, gosh that makes sense. Ligaments are pretty fixed things - little stretch - that are used to support attachments around joints and often over joint capsules. In many ways, the RCM's mirror this role.

. There Calais-Germain uses the term "active ligaments" to describe the function of these muscles. Considering that it's the tendon part of the muscles that usually comes to grief when we talk about overuse injuries or RC problems, gosh that makes sense. Ligaments are pretty fixed things - little stretch - that are used to support attachments around joints and often over joint capsules. In many ways, the RCM's mirror this role.

Indeed, every movement that a muscle in the rotator cuff supports "weakly" there is a complementary big muscle to do, literally, the heavy lifting. So let's look at these big lifters next.

Extrinsic muscles of the glenohumeral joint: the heavy lifters. The big movers of the arm are the deltoids, mapping mainly to the action of the supraspinatus, the lats, mapping mainly to the infraspinatus and teres minor, and the pecs with the subscapularis. Mainly. There's also the corachoid brachialis, a small but potent flexor.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

So what's it do? This will sound familiar: the front bits will elevate the arm (abduct) and going past that, flexion the arm, as well as turn the arm in. The mid part will also abduct or lift the arm up to the side - as in a "side lateral raise" move. And the back part will do that horizontal abduction thing while rotating the arm out. So front rotates in; back rotates out. Cool that one muscle has these opposing motions within it.

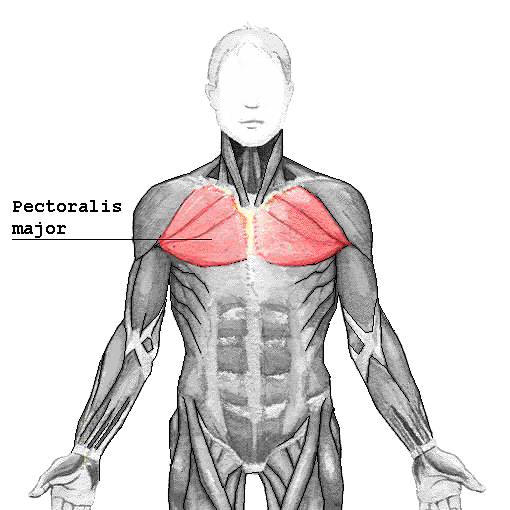

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The muscle attaches around the clavicle at the top and then along the sternum (middle of the rib cage). It plugs into the frontish of the humerous at yet another tubercle, the "intertubercular groove."

The pec's upper fibers turns the arm in as well as pulling the arm across in horizontal adduction. We see horizontal adduction when we bear hug someone. The lower fibers also support horizontal adduction and internal rotation, but they also complement the lats' action of extension from flexion down to neutral (arm at side).

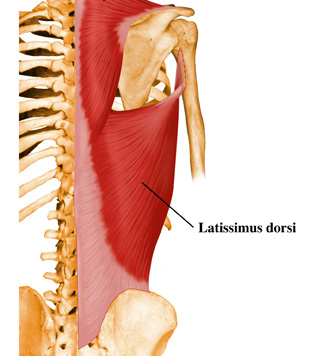

The lats - i've written about the action of the latisimus dorsi in relation to the pull up and the swing elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that it's a great big muscle that runs along the bottom half of the thoracic spine and into/onto the hip and attaches to the inside (medial lip) of the humerus.

The action here is to pull the arm back (horizontal abduction) also to extend the arm back down (extention) past where the pecs can get to, rotate the arm in, and bring it down/across the body.

Aside - you've likely noted that with the body, if there's a greater somewhere there's a lesser; if there's a minor there's a major.

The Little Lats: the Teres Major Tucked away on the back of teh scapula is one more muscle - the teres major. It is not a rotator cuff muscle; it attaches on the humerous not up at the head but just behind where the lats attahes at the medial lip of the intertubercular groove. It's main action difference from the lats is that, when the arm is out at the side (abducted) it helps pull the arm back down to the side.

It complements the lats, the pecs and works with the rhomboids.

RCM vs Extrinsic Muscles - Local vs Global or Hinges vs Handles.

So what's with the duplication of effort between the rotator cuff muscles (intrinsic g/h muscles) and these big muscles? If we use the model of active ligaments for the rotator cuff, i think we're away: the RCM's have the local job of just focusing on the socket: keeping the humeral head in that fosa and supporting that contact while the joint is moving. Snug snug snug. Hang on tight.

The big muscles are all about levers - all about really lifting the whole upper arm up, out, over, down, across and back with load. And to do big lifts we need both big fat rope and length.

Consider openning a door. The hinges hold the door in place and hold it up - they're close to the edge of the plank that moves around the door attached to the lintel. Great. They're not huge, but they're strong and do the hinge job nicely of keeping the door in place and letting it move when it's moved.

But what does this big moving action? The big handle on the door enables force to be used to open the door more easily. We know with heavy doors, some handles are also really big bars and can be grabbed with both hands. Why so far from the hinge and so big? If the handle were right close to the hinge, or even in the middle of the door - short lever - a heavy door is hard to open - maybe immovable. Indeed, putting a lot of force on a small handle close to a hinge may simply wreck the handle and still not open the door.

When the handle is close to the end opposite the hinge, then the width of the door becomes the length of the lever and a longer lever (in this case acting like a wheel barrow type lever) can make a big door easy or easier to move. Having a big handle means more force can be applied more easily, to the lever as well. Consider the teres major on the scapula complementing the pull on the humerus of the lat - kinda like a two handed pull.

Likewise, we can look at position: the pecs pull from the arm to the furthest possible point away - the middle of the front of the body. The lats also go to the arm from the middle of the back of the body. With the delts, which are well supported by the pecs and the lats - likewise these muscles run almost to the middle of the top of the scap and the clavicle and then into near the middle of the humerus, like a tetter totter.

So why all these injuries? A modest proposal.

SO if the rotator cuffs are just support muscles, and there are these big levers to move the arm when loaded, why are they getting hurt so much of the time? That's a good question. Let's assume we're not talking about accidents where someone flies into one's shoulder, rips it off, or one falls on the shoulder and dislocates it, ripping tendons. Or let's also assume there's not some genetic defect that causes tendons to rub against a deformation in bone. From here, it seems a biggie issue in athletes is "overuse" injuries of various kinds, resutling in various kinds of tendinopathies (discussed with respect to the shoulder, over here).

When do these kinds of injuries usually happen? For instance why do i get issues with my left shoulder not my right? After months of double pressing was i listening to my left shoulder or my right during sets? was i relecutant to stop when my left may have been flagging a little more than my right? did that cause me to hyperextend my shoulder a bit, and cause the supraspinatus to rub against the acromium and inflame and pull and get messed up?

In other words, can a lot of overuse injuries be put down to form failure of one kind or another? Shoulder overuse issues are really common in swimming apparently - is one side of teh stroke less perfect than the other causing the support muscles to do more work than the big muscles?

Practice to avoid Failure?

There are lots of folks who have lots of programs for strengthening the rotator cuff, rehabbing it and all that. Maybe that's great and appropriate. Me, i'm wondering however if focusing on the site is missing the source of an issue. How often is an overuse injury for instance the fault of the little muscle that pays the price rather than limitations in the effectiveness of the big muscles?

How might one know? My bias is a movement assessment.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

How might one address the issue? Suppose one has done their movement assessment and has a bunch of specific movement oriented work. Then joint mobility work as part of normal practice, and exercises that support one's practice (like the turkish get up and the windmill for the shoulder) are going to assist in good holistic movement.

Likewise, everyone needs a coach. It really pays to have an experienced coach look at our form and critique it and tune it. Some of us have never had an expert look at our movement. Hopefully the complexity of the above muscular interaction will provide good reason to make sure the movements we are performing are optimally supporting the way we move best to perform an exercise - and to be ready to quit when that form fails.

Summary

Scapula Moves for Greater ROM. In the first part of this series, we saw that the scapula moves up and down, back and forth and rotates up and down too for depression, elevation protraction retraction upward and downward rotation - all to extend the possible range of motion of the shoulder

RCMs In this part of the series we've seen how the arm that the scapula is moving about to extend its reach is both held to the body at the joint via the rotator cuff muscles - and more particularly how the big movers like the lats and the pecs especially and the delts in concert with these actually LIFT the arm up down around and back from these various scapular positions.

Glenohumeral Joint We've considered the role of the rotator cuff as local stabilizers or "active ligaments" to keep the arm in the socket for when the global levers of muscles are moving the humerus through its range of motion especially with load. That the rotator cuff muscles are like door hinges to hold the door in place so it can move, and that the big muscles are like the action on the well positioned lever to open the door.

Based on this model, we've considered that when injuries to the little support muscles occur it may be not always be becuase of particular weakness on their part but because of more systemic failure on the part of the grosser movement. As such, tuning our movement is a good idea, and we can do this by working on the range of motion of our joints, our movement quality with practice of rich multiplanar movements like the turkish get up and windmill, and that we can get a pair of pracitced eyes on our form at least from time to time to ensure we're moveing as well as we think we are.

Coda

This two part series is by no means exhaustive in terms of the shoulder girdle or joint - i haven't even touched on the role of the clavicle or the role of elbow flexors and extensors that connect into the shoulder. Nor have we talked about the nerves running through the shoulder and how neck mobility can consequently help with shoulder movement.

Really this two parter has just been meant to share some appreciation of the three core components of shoulder movement: that the scapula moves to support range of motion; that the rotator cuff holds the arm moving with that scapula and that the big arm movers lift/pull that arm as its stabilized in that joint. That story is told in the amazingly odd shape of the scapula.

I hope these pieces may inspire folks to explore a little deeper or at least help make a bit more sense of what's happening in the shoulder and from here help make a bit more sense of our own movement practice.

Any mistakes in here - including soggy analogies - are mine.

best

mc

Related

In this piece, we'll overview those pixie rotator cuff muscles and look at why they can be such a pain - in the shoulder - and how understanding the movements these muscles support may help reduce injury risk.

We'll also take a quick look at the big muscles like the lats that opperate on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumral joint. From here we'll speculate about shoulder injuries and habits to avoid them.

The shoulder tour part II: The Glenohumeral Action

Rotator Cuff What is it with the rotator cuff? we hear about so many injuries to the shoulder, and we likewise hear so much about the need to "prehab" these muscles to defeat injury. And i'm not a bystander here: i've likewise run my shoulder into the wall and shook my head to say "what is this pain? what is this thing? what needs to change? what the heck is wrong here?" I've had folks say "ah, that's the supraspinatus most like" -Um, could you unpack that a bit? No? ok. So here's a go at trying to get a little better understanding of a bit of what's happening with the rotator cuff.

First, the GlenoHumeral Joint. In moving to the rotator cuff, we're moving away from a focus on the shoulder girdle and the movement of the scapula to the main reason for the scapula: the gleno-humeral connection - or connecting the extremity that is the arm to the trunk of the body - the upper body in particular.

Where that connection takes place is with the humeral head of the humerous being knit into the glenoid cavity (or fossa) of the scapula. Note again the side view of the scapula - the glenoid fossa is rather shallow, but there's a liner/washer called the glenoid labrum that gets inset into that cavity before the humeral head makes contact. And then there's a capsule that goes around that unit, and ligaments around that. Those ligaments are kind of like a snugly-but-loosely laced sneakers - there's some give because of all the range of motion in the shoulder. This looseness - it's a bug; it's a feature.

Rotator Cuff Job 1 - holding ball in socket.

Just for context, there are four rotator cuff muscles: 1 on top, the SUPRAspinatus, 1 covering the front that goes against the underside of the scapula that is against the ribs the SUBscapularis, and two on the back of the scapula, the infraspinatus and and the teres minor

The top muscle, the supraspinatus (supra=above the spiney bit), attaches from the top of the scapula at the big scapula spine, runs along the top of that ridge, goes under the acromium process of the scapular spine, over the bursa on the top of the glenohumeral capsule and then attaches onto a big bump at the top of the humerus, the greater tubercle. That is a very popular attachment point - like the superior spine of the scapula but much smaller a peak. So when this muscle contracts, it's going to help pull the arm up to 90 degrees from one's side - called abduction. Note i say "help" - we'll come back to this assistance role. Mainly it's stabilizing the ball of the humerus in the glenoid socket.

The subscapularis which attaches along the entire scapula underside (the scapula fossa) the attaches around the front of the humerus at the lesser tubercle. If you imagine these fibers contracting, they're going to contribute to turning the humerus in (internal rotation), pulling the humerus across the body, pulling the arm back (into extension) and, of course 'stabilizing the humeral head in the glenoid fosa' - as the manual of structural kinesiology

The infraspinatus is the complement to the subscapularis: subscapularis = under(side) of the scapula; infraspinatus means below the spiney bit. Names are nicely descriptive. Where the subscapularis covers the underside of the scapula, the infraspinatus covers the whole backside of the scapula below that big scapular spine. Where the supraspinatus attaches to the top of the greater tubercle, the infraspinatus attaches to the back of the greater tubercle. So again, if we imagine pulling / contracting that attachment, the kinds of things that can happen to the arm are - its turned out (externally rotated), it's also going to pull the arm back into extension. It also helps with what's known as horizontal abduction. Big role - stabilize the arm in the socket - we might add especially when it's being moved about.

The teres minor is like a support for the infraspinatus. Teres just means round and smooth (cylyndrical). and that's sort of what this muscle is. It hangs onto the lateral border of the scapula (the edge closer to the arm), and then plugs in under the greater tubercle of the humerus. So what's it going to do? Exactly the same as the infraspinatus: *stabilization,*external rotation, extension and horizontal abduction.

Note: horizontal abduction is different from abduction: abduction, the arm is being raised up at the side; horizontal abduction assumes that the arm is already up at ninety degrees and infront of the body, and so the arm is being pulled back (abduction - ab is latin for from, as in away from rather that ad, to, towards).

Summary of RCM Action That's it: 4 muscles with pretty functionally descriptive names.

They all have four things in common:

- they all attach to the scapula

- they each attach near the humeral head

- they all primarily stabilize the the arm in its socket.

- they all rotate the arm in the socket either up, in or out (hence the name, rotator)

They're so WEAK, what's the point of being muscles?

In reading kinesiology texts, a word repeated all the time about the rotator cuff muscles is "weak" - they provide weak adduction, weak abduction, weak rotation - weak weak weak. no leverage. like a person trying to open a door when the handle is in the middle of the door.

If they're so weak what are they doing there? One of the best reframings of the roll of the RCMs is in the Anatomy of Movement

Indeed, every movement that a muscle in the rotator cuff supports "weakly" there is a complementary big muscle to do, literally, the heavy lifting. So let's look at these big lifters next.

Extrinsic muscles of the glenohumeral joint: the heavy lifters. The big movers of the arm are the deltoids, mapping mainly to the action of the supraspinatus, the lats, mapping mainly to the infraspinatus and teres minor, and the pecs with the subscapularis. Mainly. There's also the corachoid brachialis, a small but potent flexor.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.

The deltoid is usually considered the main "shoulder" muscle. It's a goodly three part triangular mass that connects on both the first third of the scapula, around the front of the acromion process and into the under edge of the scap spine. And the next big deal is that it attaches to the humerous at its very own "deltoid tuberosity" of the humerus.So what's it do? This will sound familiar: the front bits will elevate the arm (abduct) and going past that, flexion the arm, as well as turn the arm in. The mid part will also abduct or lift the arm up to the side - as in a "side lateral raise" move. And the back part will do that horizontal abduction thing while rotating the arm out. So front rotates in; back rotates out. Cool that one muscle has these opposing motions within it.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.

The pec major - the big chest muscle - likewise has mutlipte parts: upper or clavicular and lower or sternal.The muscle attaches around the clavicle at the top and then along the sternum (middle of the rib cage). It plugs into the frontish of the humerous at yet another tubercle, the "intertubercular groove."

The pec's upper fibers turns the arm in as well as pulling the arm across in horizontal adduction. We see horizontal adduction when we bear hug someone. The lower fibers also support horizontal adduction and internal rotation, but they also complement the lats' action of extension from flexion down to neutral (arm at side).

The lats - i've written about the action of the latisimus dorsi in relation to the pull up and the swing elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that it's a great big muscle that runs along the bottom half of the thoracic spine and into/onto the hip and attaches to the inside (medial lip) of the humerus.

The action here is to pull the arm back (horizontal abduction) also to extend the arm back down (extention) past where the pecs can get to, rotate the arm in, and bring it down/across the body.

Aside - you've likely noted that with the body, if there's a greater somewhere there's a lesser; if there's a minor there's a major.

The Little Lats: the Teres Major Tucked away on the back of teh scapula is one more muscle - the teres major. It is not a rotator cuff muscle; it attaches on the humerous not up at the head but just behind where the lats attahes at the medial lip of the intertubercular groove. It's main action difference from the lats is that, when the arm is out at the side (abducted) it helps pull the arm back down to the side.

It complements the lats, the pecs and works with the rhomboids.

RCM vs Extrinsic Muscles - Local vs Global or Hinges vs Handles.

So what's with the duplication of effort between the rotator cuff muscles (intrinsic g/h muscles) and these big muscles? If we use the model of active ligaments for the rotator cuff, i think we're away: the RCM's have the local job of just focusing on the socket: keeping the humeral head in that fosa and supporting that contact while the joint is moving. Snug snug snug. Hang on tight.

The big muscles are all about levers - all about really lifting the whole upper arm up, out, over, down, across and back with load. And to do big lifts we need both big fat rope and length.

Consider openning a door. The hinges hold the door in place and hold it up - they're close to the edge of the plank that moves around the door attached to the lintel. Great. They're not huge, but they're strong and do the hinge job nicely of keeping the door in place and letting it move when it's moved.

But what does this big moving action? The big handle on the door enables force to be used to open the door more easily. We know with heavy doors, some handles are also really big bars and can be grabbed with both hands. Why so far from the hinge and so big? If the handle were right close to the hinge, or even in the middle of the door - short lever - a heavy door is hard to open - maybe immovable. Indeed, putting a lot of force on a small handle close to a hinge may simply wreck the handle and still not open the door.

When the handle is close to the end opposite the hinge, then the width of the door becomes the length of the lever and a longer lever (in this case acting like a wheel barrow type lever) can make a big door easy or easier to move. Having a big handle means more force can be applied more easily, to the lever as well. Consider the teres major on the scapula complementing the pull on the humerus of the lat - kinda like a two handed pull.

Likewise, we can look at position: the pecs pull from the arm to the furthest possible point away - the middle of the front of the body. The lats also go to the arm from the middle of the back of the body. With the delts, which are well supported by the pecs and the lats - likewise these muscles run almost to the middle of the top of the scap and the clavicle and then into near the middle of the humerus, like a tetter totter.

So why all these injuries? A modest proposal.

SO if the rotator cuffs are just support muscles, and there are these big levers to move the arm when loaded, why are they getting hurt so much of the time? That's a good question. Let's assume we're not talking about accidents where someone flies into one's shoulder, rips it off, or one falls on the shoulder and dislocates it, ripping tendons. Or let's also assume there's not some genetic defect that causes tendons to rub against a deformation in bone. From here, it seems a biggie issue in athletes is "overuse" injuries of various kinds, resutling in various kinds of tendinopathies (discussed with respect to the shoulder, over here).

When do these kinds of injuries usually happen? For instance why do i get issues with my left shoulder not my right? After months of double pressing was i listening to my left shoulder or my right during sets? was i relecutant to stop when my left may have been flagging a little more than my right? did that cause me to hyperextend my shoulder a bit, and cause the supraspinatus to rub against the acromium and inflame and pull and get messed up?

In other words, can a lot of overuse injuries be put down to form failure of one kind or another? Shoulder overuse issues are really common in swimming apparently - is one side of teh stroke less perfect than the other causing the support muscles to do more work than the big muscles?

Practice to avoid Failure?

There are lots of folks who have lots of programs for strengthening the rotator cuff, rehabbing it and all that. Maybe that's great and appropriate. Me, i'm wondering however if focusing on the site is missing the source of an issue. How often is an overuse injury for instance the fault of the little muscle that pays the price rather than limitations in the effectiveness of the big muscles?

How might one know? My bias is a movement assessment.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there.

Consider if the problem in the shoulder is from lack of good mobility in the thoracic spine. Or if the issue has to do with poor firing of the lat to support the shoulder. Will rotator cuff-focused rehab hit these issues? In other words, my bias is to consider at least first what the larger movement issues may be and work from there. How might one address the issue? Suppose one has done their movement assessment and has a bunch of specific movement oriented work. Then joint mobility work as part of normal practice, and exercises that support one's practice (like the turkish get up and the windmill for the shoulder) are going to assist in good holistic movement.

Likewise, everyone needs a coach. It really pays to have an experienced coach look at our form and critique it and tune it. Some of us have never had an expert look at our movement. Hopefully the complexity of the above muscular interaction will provide good reason to make sure the movements we are performing are optimally supporting the way we move best to perform an exercise - and to be ready to quit when that form fails.

Summary

Scapula Moves for Greater ROM. In the first part of this series, we saw that the scapula moves up and down, back and forth and rotates up and down too for depression, elevation protraction retraction upward and downward rotation - all to extend the possible range of motion of the shoulder

RCMs In this part of the series we've seen how the arm that the scapula is moving about to extend its reach is both held to the body at the joint via the rotator cuff muscles - and more particularly how the big movers like the lats and the pecs especially and the delts in concert with these actually LIFT the arm up down around and back from these various scapular positions.

Glenohumeral Joint We've considered the role of the rotator cuff as local stabilizers or "active ligaments" to keep the arm in the socket for when the global levers of muscles are moving the humerus through its range of motion especially with load. That the rotator cuff muscles are like door hinges to hold the door in place so it can move, and that the big muscles are like the action on the well positioned lever to open the door.

Based on this model, we've considered that when injuries to the little support muscles occur it may be not always be becuase of particular weakness on their part but because of more systemic failure on the part of the grosser movement. As such, tuning our movement is a good idea, and we can do this by working on the range of motion of our joints, our movement quality with practice of rich multiplanar movements like the turkish get up and windmill, and that we can get a pair of pracitced eyes on our form at least from time to time to ensure we're moveing as well as we think we are.

Coda

This two part series is by no means exhaustive in terms of the shoulder girdle or joint - i haven't even touched on the role of the clavicle or the role of elbow flexors and extensors that connect into the shoulder. Nor have we talked about the nerves running through the shoulder and how neck mobility can consequently help with shoulder movement.

Really this two parter has just been meant to share some appreciation of the three core components of shoulder movement: that the scapula moves to support range of motion; that the rotator cuff holds the arm moving with that scapula and that the big arm movers lift/pull that arm as its stabilized in that joint. That story is told in the amazingly odd shape of the scapula.

I hope these pieces may inspire folks to explore a little deeper or at least help make a bit more sense of what's happening in the shoulder and from here help make a bit more sense of our own movement practice.

Any mistakes in here - including soggy analogies - are mine.

best

mc

Related

- part 1 of the amazing shoulder: the scapula and shoulder girdle

- why move or die?

- what's mobility pracice?

- training to avoid the sprain: iphase

- nice piece in am. fam. physician on shoulder instability

- nice ref on SLAP tears in the context of baseball players - great figures.

Labels:

glenohumeral,

shoulder

Sunday, June 20, 2010

the amazing engineering that is the shoulder, part 1: scapula and shoulder girdle

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

How does the shoulder really work? What is it, anyway? When we think of working the shoulder, most of us likely think of the delts, maybe the traps (shoulder shrugs and all). When we think about shoulder injuries, the term "rotator cuff" enters the vocabulary and we worry about how to prehab/rehap these little stabilizer muscles. But really, the shoulder, or more particularly the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle is an amazing feat of evolutionary engineering, so much so that most of what we tend to think of as uppert body work is really shoulder work.

Consider that we usually think of the lats, traps, rhomboids all as back muscles, and the pecs and seratus anterior as chest muscles. Yes, ok, that's more about where those muscles are located, but they're all, really really, shoulder muscles. Even the triceps and biceps are involved as shoulder muscles - and require the shoulder as their anchoring points.

Consider that we usually think of the lats, traps, rhomboids all as back muscles, and the pecs and seratus anterior as chest muscles. Yes, ok, that's more about where those muscles are located, but they're all, really really, shoulder muscles. Even the triceps and biceps are involved as shoulder muscles - and require the shoulder as their anchoring points.

Understanding a little bit more about how the shoulder works in terms of where the muscles attach to what and how they act on the shoulder may help enhance our lifting, prevent injury, and help us understand what we're doing - or not - when we think about working out.

So the goal of this set of posts on the shoulder is to offer a wee tour through the shoulder, and provide further resources if you get fired up to look further.

Part 1: the Scapula and Shoulder Girdle

In structural kinesiology - the study of movement in terms of nerves, bones and muscles and joints - there are two main ways to look at the shoulder: the shoulder girdle and the shoulder joint. Both of these views considers one of the weirdest and coolest bones in the body, the shoulder blade or scapula.

In this first of two parts looking at the shoulder, we'll first take a quick look at the multifacetted structure of the scapula and also look at the muscles associated with the shoulder girdle - or the muscles primarily involved with moving the scapula itself.

In part two, we'll look at the muscles acting on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumeral joint (gh), from the rotator cuff muscles to the lats and pec major.

The Scapula: It's a wild wild bone.

This figure above shows three views of the scapula: the front side that faces the back of the ribs, the back side that we can feel or palpate, especially along that honking big spine, and where the magic focuses, the side on view that features the glenoid cavity - the aras where the arm - in particular the humerous fits into the shoulder.

Take a look at the ridges and bumps: every bit of an indentation or edge has a purpose in the muscular rigging that is the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle.

Overview: Let's take a quick look at the shoulder girdle muscles to get a sense of the specialness of the shoulder girdle design and what i mean by this rigging - and possibly why this approach in our design (is so cool).

The scapula first and foremost is situated behind and at the top of the rib cage. It has muscles attached to both sides of it: there are muscles along it's back; and muscles along its front. The ones we're looking at here are the ones that primarily move the scapula, and help keep it in position along the back of the rib cage.

As said, each bump, dip and pointy part of the scapula has a mechanical design purpose. By way of example, the image to the left shows the back view of the scapula. In red, the levator scapula is attached to the superior border of the scapula. This shoulder muscle, while attached up at the top four vertebrae in the neck is not a neck muscle per se, but exists to help pull the scapula up (and a bit towards the spine, elevation and adduction)

If we look back at the image of the scapula bone, we see the medial border on the back/posterior side of the scap. Follow along to the medial border (left side of spine in the image with the levator scap shown) and the minor and major rhomboids are attached there and plug into the bottom of the cervical spine, and top half of the thoracic spine. If we just follow the line of the muscles, which go up diagonally, we can see that when they contract they'll pull the scapula towards the spine and up in elevation, but actually in doing so, can also rotate the shoulder socket down. We'll come back to why this rotation is important.

On the other side of the spine we see another rich and amazing attachment, the trapezius which is considered in three parts. The upper fibers attach along the far end of the clavicle or collar bone and the scapula's acromial process, and also along the start of the big spine on the back of the scapula. Again shoulder elevation helped here as well as adduction. Then the middle fibers which attach a little along the scapula spine, but also this time, rotate the socket up. The lower fibers of this massive muscle which connect on the scapula spine under side-ish area. These also contribute to pulling the shoulder socket up, but also bringing the shoulder down blade down.

To take a quick look at the front-ish part of the scapula, there's the pec minor and the seratus anterior.

The pec minor attaches to the scapula at the coricoid process (the biceps at one point do, too, among others) and then into the ribs. Again, if we follow the line of the muscles, we can see that when contracted, these muscles will pull the scapula, well, rather over the shoulder, rotating the socket downwards. The scapula also gets pulled away from the spine (abducted), and likewise dowward (depression).

The serratus anterior is an amazing set of muscles that connects all along the medial border on the inside/front of the scapula, on the opposite side from the rhomboids.

Where the rhomboids pulls the scap up and towards the spine, the seratus anterior pulls the scapula away from the spine and the scapula up at the same time via the attachment upwards along the sides of the ribs. The joint tension of the rhomboids and the serratus anterior both help keep the scapula down against the ribs in movements like the push up.

Why all this Scapular Movement? RANGE EXTENSION. I dunno about you, but while i've heard about shoulder depression and elevation and rotation, it hasn't meant a whole lot to me until i got to see what the bones actually do relative to what's getting rotated: the arm in the shoulder joint.

An image may help. Take a look at the relative positions of the scapulae in the picture to the right here (in red the supraspinatus is highlighted, but that ain't important right now). If we look at the left arm, we'll note that the glenoid fossa - where the humerous fits into the shoulder) is in neutral. With the right arm elevated, like in an overhead press, we see that the whole scapula is titled away from the spine and that the glenoid fossa - where the arm connects - is pointed more UP.

An image may help. Take a look at the relative positions of the scapulae in the picture to the right here (in red the supraspinatus is highlighted, but that ain't important right now). If we look at the left arm, we'll note that the glenoid fossa - where the humerous fits into the shoulder) is in neutral. With the right arm elevated, like in an overhead press, we see that the whole scapula is titled away from the spine and that the glenoid fossa - where the arm connects - is pointed more UP.

Bottom wonderful line is that, by rigging up the scapula so that it's got all these guy wired muscles holding the scapulae as a kind of floating anchor point, we get far greater range of motion with our arms than if we had a more or less fixed ball and socket joint.

That is, if the scapula, which is largely designed to act as an attachment for the upper limbs, were fixed to the spine as a bone such that the socket for the humerus was fixed ( unable to rotate up, down, back and forward), the arm would have far more restricted motion. We'd be unable to press up, cross our arms, do push ups, waltz. Awful to contemplate.

So let's not. Let's sum up where we're at today.

Summing up part 1

In this first article on the shoulder girdle & scapula, we've had a quick look at the muscles that support the movement of the scapula and concurrently the resulting rotation of the glenohumeral joint that allows for the all important rich range of motion of the arm at the shoulder.

Next, we'll look at the muscles acting on the glenohumeral joint, like the giant lats, pec major, teres major, and including those pixie trouble makers, the rotator cuff muscles. Guarenteed once we go over how they work and where they are in the scapula, remembering the names of the four will be simple.

But heck, isn't that scapula an amazing bone or what, eh?

Resources

Some great books to help get into structural kinesiology are

Manual of Structural Kinesiology

Manual of Structural Kinesiology

really really good source for getting at the complete details on joints, muscles, actions, planes of motion, nerves. THere are great exercises and quizes with the book as well for self-testing

really really good source for getting at the complete details on joints, muscles, actions, planes of motion, nerves. THere are great exercises and quizes with the book as well for self-testing

Anatomy of Movement (Revised Edition)

A very personable look at anatomy in the context of not only athletic but every day movements.

And for getting into the actual feel of where these muscles are and how they operate live, there is the very popular Trail Guide to the Body Book

And for getting into the actual feel of where these muscles are and how they operate live, there is the very popular Trail Guide to the Body Book

And heck if you've ever tried to figure out whether that groin pull is an adductor magus or gracialis, this is the one for you.

More books that include seeing the real tissue (making the case for illustrations) next time.

Related posts:

Consider that we usually think of the lats, traps, rhomboids all as back muscles, and the pecs and seratus anterior as chest muscles. Yes, ok, that's more about where those muscles are located, but they're all, really really, shoulder muscles. Even the triceps and biceps are involved as shoulder muscles - and require the shoulder as their anchoring points.

Consider that we usually think of the lats, traps, rhomboids all as back muscles, and the pecs and seratus anterior as chest muscles. Yes, ok, that's more about where those muscles are located, but they're all, really really, shoulder muscles. Even the triceps and biceps are involved as shoulder muscles - and require the shoulder as their anchoring points.Understanding a little bit more about how the shoulder works in terms of where the muscles attach to what and how they act on the shoulder may help enhance our lifting, prevent injury, and help us understand what we're doing - or not - when we think about working out.

So the goal of this set of posts on the shoulder is to offer a wee tour through the shoulder, and provide further resources if you get fired up to look further.

Part 1: the Scapula and Shoulder Girdle

In structural kinesiology - the study of movement in terms of nerves, bones and muscles and joints - there are two main ways to look at the shoulder: the shoulder girdle and the shoulder joint. Both of these views considers one of the weirdest and coolest bones in the body, the shoulder blade or scapula.

In this first of two parts looking at the shoulder, we'll first take a quick look at the multifacetted structure of the scapula and also look at the muscles associated with the shoulder girdle - or the muscles primarily involved with moving the scapula itself.

In part two, we'll look at the muscles acting on the main shoulder joint, the glenohumeral joint (gh), from the rotator cuff muscles to the lats and pec major.

The Scapula: It's a wild wild bone.

This figure above shows three views of the scapula: the front side that faces the back of the ribs, the back side that we can feel or palpate, especially along that honking big spine, and where the magic focuses, the side on view that features the glenoid cavity - the aras where the arm - in particular the humerous fits into the shoulder.

Take a look at the ridges and bumps: every bit of an indentation or edge has a purpose in the muscular rigging that is the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle.

Overview: Let's take a quick look at the shoulder girdle muscles to get a sense of the specialness of the shoulder girdle design and what i mean by this rigging - and possibly why this approach in our design (is so cool).

The scapula first and foremost is situated behind and at the top of the rib cage. It has muscles attached to both sides of it: there are muscles along it's back; and muscles along its front. The ones we're looking at here are the ones that primarily move the scapula, and help keep it in position along the back of the rib cage.

As said, each bump, dip and pointy part of the scapula has a mechanical design purpose. By way of example, the image to the left shows the back view of the scapula. In red, the levator scapula is attached to the superior border of the scapula. This shoulder muscle, while attached up at the top four vertebrae in the neck is not a neck muscle per se, but exists to help pull the scapula up (and a bit towards the spine, elevation and adduction)

If we look back at the image of the scapula bone, we see the medial border on the back/posterior side of the scap. Follow along to the medial border (left side of spine in the image with the levator scap shown) and the minor and major rhomboids are attached there and plug into the bottom of the cervical spine, and top half of the thoracic spine. If we just follow the line of the muscles, which go up diagonally, we can see that when they contract they'll pull the scapula towards the spine and up in elevation, but actually in doing so, can also rotate the shoulder socket down. We'll come back to why this rotation is important.

On the other side of the spine we see another rich and amazing attachment, the trapezius which is considered in three parts. The upper fibers attach along the far end of the clavicle or collar bone and the scapula's acromial process, and also along the start of the big spine on the back of the scapula. Again shoulder elevation helped here as well as adduction. Then the middle fibers which attach a little along the scapula spine, but also this time, rotate the socket up. The lower fibers of this massive muscle which connect on the scapula spine under side-ish area. These also contribute to pulling the shoulder socket up, but also bringing the shoulder down blade down.

To take a quick look at the front-ish part of the scapula, there's the pec minor and the seratus anterior.

The pec minor attaches to the scapula at the coricoid process (the biceps at one point do, too, among others) and then into the ribs. Again, if we follow the line of the muscles, we can see that when contracted, these muscles will pull the scapula, well, rather over the shoulder, rotating the socket downwards. The scapula also gets pulled away from the spine (abducted), and likewise dowward (depression).