Showing posts with label work out. Show all posts

Showing posts with label work out. Show all posts

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

Running the Bells - Intense Kettlebell Cardio "Hill" Workouts

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

When road biking, once a week, hill workouts were the mission. Strength to climb and endure the climb, when the angle is causing the heart to work harder is a great general workout too. Of course one of the great parts is coming down the other side for recovery.

Runners also use hill workouts to help develop speed (short fast steep climbs with lots of recovery) and longer hill climbs like cyclists for endurance/stamina.

It's possible to simulate the cardio aspects of hill workouts with kettlebells both for conditioning, endurance, and, of course, body composition/fat loss. Not sure if it will translate to the speed benefits, but i'd hypothesize there may be some carryover. But let's leave that question aside for the moment and focus on the endurance strength and cardio.

So, here's one way i've found to get a great endurance workout in, similar to my cycling hill workouts, and that may be more enjoyable or engaging than simply swinging for sets.

Running the Bells Set Up

Here's how running the bells works, and it's pretty simple. First, set the timer on 15 mins. Then, line up a set of bells, for me that's 8, 12, 16, 20, 24. I do 10 swings per bell going up, then come back down 10 each. The point is to keep swinging. That's different than most swing sets for time: it's not X swings then break, or swing for 2 mins then break. It's no break. The recovery is in the coming down the hill - the progressively lighter bells coming back down.

Here's how running the bells works, and it's pretty simple. First, set the timer on 15 mins. Then, line up a set of bells, for me that's 8, 12, 16, 20, 24. I do 10 swings per bell going up, then come back down 10 each. The point is to keep swinging. That's different than most swing sets for time: it's not X swings then break, or swing for 2 mins then break. It's no break. The recovery is in the coming down the hill - the progressively lighter bells coming back down.

The no. of swings per bell can be varried too if you want to make the hills steeper or the flats longer. You could even line up bells this way if you wanted in a tour de france of varying sizes, eg 8, 12, 12, 16,12,20, 24, sudden drop to 12, 20, 12, 8, 8. Another alternative is to change the counts for the bells, do the number of swings of that size bell. etc.

It's (usually) about Time

What you may want to consider, though, is planning your route before you start. So set up either the bells or the rep scheme (or both) before starting so you have a strategy in mind, and progress you can monitor, and then adjust for the next time. And then keep going for time. You may want to give a run a test drive to see how it feels for you.

You may decide you don't want to work for time - that you say "i just want to run the course 3 times and just see how long that takes me"

For me, going for time may be a hang over from running/cycling, where time is about endurance, and you're looking at the distance covered in that time improving.

But also, when you're thinking about body comp goals, getting longer sets in is a good thing, so if you can do your hills non-stop for 15 mins (that 8 can come in really handy to be able to keep swinging non stop when forearms are no longer able to help hang onto the 24). When you're feeling really good, you can go for more sets. A typical hill workout on the bike was an hour. I'll tell ya, i have not done these hill workouts for that long with KB's. A couple 15 min sets has been it.

Variety, Endurance, Body Comp - and Grip

Running the bells is a way to bring some variety into my kettlebell practice, and let me focus on a different part of my conditioning - stamina/endurance - while burning a whole lot of calories, giving me a hybrid resistance/cardio workout, and hitting the backside and grip all at the same time.

Really - the grip work is not to be underestimated as part of an endurance workout. That just doesn't happen on a bike, and only partially on a rower. This grip work is just one of the many not so hidden benefits of kettlebells.

Let me know if you give Running the Bells a shot and how you find 'em.

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Runners also use hill workouts to help develop speed (short fast steep climbs with lots of recovery) and longer hill climbs like cyclists for endurance/stamina.

It's possible to simulate the cardio aspects of hill workouts with kettlebells both for conditioning, endurance, and, of course, body composition/fat loss. Not sure if it will translate to the speed benefits, but i'd hypothesize there may be some carryover. But let's leave that question aside for the moment and focus on the endurance strength and cardio.

So, here's one way i've found to get a great endurance workout in, similar to my cycling hill workouts, and that may be more enjoyable or engaging than simply swinging for sets.

Running the Bells Set Up

Here's how running the bells works, and it's pretty simple. First, set the timer on 15 mins. Then, line up a set of bells, for me that's 8, 12, 16, 20, 24. I do 10 swings per bell going up, then come back down 10 each. The point is to keep swinging. That's different than most swing sets for time: it's not X swings then break, or swing for 2 mins then break. It's no break. The recovery is in the coming down the hill - the progressively lighter bells coming back down.

Here's how running the bells works, and it's pretty simple. First, set the timer on 15 mins. Then, line up a set of bells, for me that's 8, 12, 16, 20, 24. I do 10 swings per bell going up, then come back down 10 each. The point is to keep swinging. That's different than most swing sets for time: it's not X swings then break, or swing for 2 mins then break. It's no break. The recovery is in the coming down the hill - the progressively lighter bells coming back down.The no. of swings per bell can be varried too if you want to make the hills steeper or the flats longer. You could even line up bells this way if you wanted in a tour de france of varying sizes, eg 8, 12, 12, 16,12,20, 24, sudden drop to 12, 20, 12, 8, 8. Another alternative is to change the counts for the bells, do the number of swings of that size bell. etc.

It's (usually) about Time

What you may want to consider, though, is planning your route before you start. So set up either the bells or the rep scheme (or both) before starting so you have a strategy in mind, and progress you can monitor, and then adjust for the next time. And then keep going for time. You may want to give a run a test drive to see how it feels for you.

You may decide you don't want to work for time - that you say "i just want to run the course 3 times and just see how long that takes me"

For me, going for time may be a hang over from running/cycling, where time is about endurance, and you're looking at the distance covered in that time improving.

But also, when you're thinking about body comp goals, getting longer sets in is a good thing, so if you can do your hills non-stop for 15 mins (that 8 can come in really handy to be able to keep swinging non stop when forearms are no longer able to help hang onto the 24). When you're feeling really good, you can go for more sets. A typical hill workout on the bike was an hour. I'll tell ya, i have not done these hill workouts for that long with KB's. A couple 15 min sets has been it.

Variety, Endurance, Body Comp - and Grip

Running the bells is a way to bring some variety into my kettlebell practice, and let me focus on a different part of my conditioning - stamina/endurance - while burning a whole lot of calories, giving me a hybrid resistance/cardio workout, and hitting the backside and grip all at the same time.

Really - the grip work is not to be underestimated as part of an endurance workout. That just doesn't happen on a bike, and only partially on a rower. This grip work is just one of the many not so hidden benefits of kettlebells.

Let me know if you give Running the Bells a shot and how you find 'em.

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

kettlebells,

work out,

workouts

Monday, December 15, 2008

mc's version of KJ's beast pressing protocol - just fyi

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Protocol Review: What do i do?

A few folks have kindly asked exactly what am i doing in this volume protocol for presses i've been writing about recently (here's the latest post). Thanks for reading and for your interest.

The following is my current rif on KJ's Beast Plan for Presses (described in the RKC manual, 2007, 2008 and the subject of a forthcoming book).

The following is my current rif on KJ's Beast Plan for Presses (described in the RKC manual, 2007, 2008 and the subject of a forthcoming book).

As said, this is a slight variant on the protocol developed by Kenneth Jay. Any compromises to that plan are entirely mine. This post is not a protocol endorsement at all - i'm just experimenting and have not completed that experiment. I'm posting this in the interest of being clear about the method of the approach. I'll continue to report my results, but i'm only a sample of one so far. If you're interested in playing along, by all means, but again, no guarentees :)

With that caveat in place, here we go:

Light Day

As soon as form on the press starts to go south - like a complete rep but needing to put in a hip - go to a lighter bell, and keep going.

I do two 15 min zones. Many challenges within this: getting to 200 reps with perfect form; getting to the complete cycle with the same weight are two good ones.

Heavy Day

Again, i set the 15min timer - not so much because i want to work for 15 mins, but because i want to make *sure* i use the full period for recovery. If i cut that short, the rep fails. That's all there is to it - at least for me. And strength work like this is 2-3 mins. The timer helps me stick to that because i HATE waiting and like to rush to do the next press. For me, that's a doomed strategy, so i use the timer. Then, with heavy bell ready,

Then recovery. Then it's onto partials. reset timer.

So, Kenneth has neat ideas here: if i don't want to do parials with a 4k jump up to the 20, i could do partials with a double bell combination. KJ is a big fan of stacking bells, even if they don't come up to the goal weight of the new bell. Here's where that happens for me: just before one heavy bell looses form.

So, the Partial recipe is to press up with the assist of the other hand, come down to sticking point; press back up; come down a little further, press up; down a little further, press up. This approach to partials is very cool. It works on both sides - where i get down to on each side is a bit different, but it's working.

Two notes on the partials: perfect form.

First, as said, if i feel form is about to get lost, i bail to go to the 16 stacked with another bell, for slightly under the 20 weight, to about an 18. Second, breathing and handle gripping.

Many folks already know this; i've heard it alot too, but it's not until i've really practiced it with this approach that i've gotten how vital it is. For me, it's

There's at least a two day gap between the light day and the heavy day for pressing, so that's *only* once a week for the complete pressing cycle. The other days of the week are currently replete with fighting despair while trying to build up my pistol and pull up, again with heavy/light days per both, snatching once a week (or so) to stay solid with the new RKC snatch test numbers, and a whole lot of rowing thrown in for fun, happiness and alternating steady state/interval cardio. Thanks to KJ there too for pointing out the similarity between rowing and snatching.

Ok, wow, surprised that took so many words to detail, but i hope that helps anyone curious about exactly what i'm doing in these sets. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

A few folks have kindly asked exactly what am i doing in this volume protocol for presses i've been writing about recently (here's the latest post). Thanks for reading and for your interest.

The following is my current rif on KJ's Beast Plan for Presses (described in the RKC manual, 2007, 2008 and the subject of a forthcoming book).

The following is my current rif on KJ's Beast Plan for Presses (described in the RKC manual, 2007, 2008 and the subject of a forthcoming book).As said, this is a slight variant on the protocol developed by Kenneth Jay. Any compromises to that plan are entirely mine. This post is not a protocol endorsement at all - i'm just experimenting and have not completed that experiment. I'm posting this in the interest of being clear about the method of the approach. I'll continue to report my results, but i'm only a sample of one so far. If you're interested in playing along, by all means, but again, no guarentees :)

With that caveat in place, here we go:

Light Day

- pick a weight i can do ten reps with and get ready for multiple sets of five

- set a timer for 15mins (i like the gymboss as a physical device & use it alot, but for a BIG screen version, this freebie javascript page rules.).

- Press strong/best side for 5 - inhale on the press/exhale on the descent. focus on form each rep.

- Press weaker/lesser side for 5

- Put the bell down

- Do TEN bodyweight DeadLifts (so focus on form, in particular, bone rhythm, so that's getting the ass down fast to finish with the knees, exhaling on the out, inhaling on the up. These are done FAST - as fast as can be done to keep that perfect bone rhythm form, yes, but also to keep the heart up to test the effect of integrated cardio)

- mark down complete set with a | in a workout book.

- Take a breath

As soon as form on the press starts to go south - like a complete rep but needing to put in a hip - go to a lighter bell, and keep going.

I do two 15 min zones. Many challenges within this: getting to 200 reps with perfect form; getting to the complete cycle with the same weight are two good ones.

Heavy Day

Again, i set the 15min timer - not so much because i want to work for 15 mins, but because i want to make *sure* i use the full period for recovery. If i cut that short, the rep fails. That's all there is to it - at least for me. And strength work like this is 2-3 mins. The timer helps me stick to that because i HATE waiting and like to rush to do the next press. For me, that's a doomed strategy, so i use the timer. Then, with heavy bell ready,

- i do my C&P on the strong side; park the bell.

- Pause for a breath to feel in the zone.

- Do my C&P on the weaker side. park the bell.

- Do z health drills during the recovery period.

- make SURE the full recovery period has passed.

- Repeat.

Then recovery. Then it's onto partials. reset timer.

So, Kenneth has neat ideas here: if i don't want to do parials with a 4k jump up to the 20, i could do partials with a double bell combination. KJ is a big fan of stacking bells, even if they don't come up to the goal weight of the new bell. Here's where that happens for me: just before one heavy bell looses form.

So, the Partial recipe is to press up with the assist of the other hand, come down to sticking point; press back up; come down a little further, press up; down a little further, press up. This approach to partials is very cool. It works on both sides - where i get down to on each side is a bit different, but it's working.

Two notes on the partials: perfect form.

First, as said, if i feel form is about to get lost, i bail to go to the 16 stacked with another bell, for slightly under the 20 weight, to about an 18. Second, breathing and handle gripping.

Many folks already know this; i've heard it alot too, but it's not until i've really practiced it with this approach that i've gotten how vital it is. For me, it's

- inhale going up; exhale coming down - it's just smoother, more in control - for me, anyway.

- grip the handle especially if in grief on going up. When i've felt my weaker side pushing through the sticking point, gripping the handle with extra force on the heavy day, and towards the end of the light day, helped keep the form groove.

There's at least a two day gap between the light day and the heavy day for pressing, so that's *only* once a week for the complete pressing cycle. The other days of the week are currently replete with fighting despair while trying to build up my pistol and pull up, again with heavy/light days per both, snatching once a week (or so) to stay solid with the new RKC snatch test numbers, and a whole lot of rowing thrown in for fun, happiness and alternating steady state/interval cardio. Thanks to KJ there too for pointing out the similarity between rowing and snatching.

Ok, wow, surprised that took so many words to detail, but i hope that helps anyone curious about exactly what i'm doing in these sets. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Monday, December 1, 2008

The Perfect Rep - and the role of volume with form.

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

This post is a reflection on one aspect that contributes to the experience of the perfect rep: high volume. It's only one part, but i'd like to unpack a bit of why that part, at least for myself, and a rather new understanding of "volume" is becoming such a key part of "perfect."

One of the first things that struck me in reading Pavel's work like Enter the Kettlebell is the emphasis on "the perfect rep." Don't go to failure; don't do so many reps that form goes to hell. Stay fresh. Make every rep perfect.

Kettlebell is the emphasis on "the perfect rep." Don't go to failure; don't do so many reps that form goes to hell. Stay fresh. Make every rep perfect.

But what is the "perfect rep"? And how do we know if we have one?

This may not be your experience, but i've interpreted this "perfect rep" thing as getting the form right mechanically, and executing with the correct weight for the correct sets and moving on, eg doing the ladders for ETK's ROP. Upon reflection, though, that progression doesn't sound much like an experience of "perfection," does it? Sure one feels good after doing the workouts, and yes progress most emphatically occurs. But is it "perfection?" And why is experiencing perfection so important? would i know it if i did encounter it?

Some time ago i wrote about how seeing Will Williams doing the kettlebell front squat - in particular the breathing to go with that move - stopped me in my tracks as seeming effortless and perfect. I'd described it as what i'd understood art to be about, when a move goes from the mechanistic to the graceful.

The parts of perfection. Last week or so, looking at the kettlebell front squat, i came back to the front squat, going over how zhealth breaks down the concept of efficient movement into four parts that seems to be a recipe for the perfect rep:

What's been hitting me of late as a key feature of even getting into step one - hitting the target/perfect form - is volume by repetition. In other words, tons of reps. Which means lighter weights.

What's a Rep, really? Generally speaking, i've thought of reps as simply reps within a set, and that volume is just whatever you get from the total reps x mass for a particular workout. Increasing reps, especially when focusing on strength, has seemed just the wrong way to think about it, too: loads of reps is endurance strength, not power strength, heh we want POWER to PRESS. And it seems many protocols for strength reinforce this. For instance, in Charles Staley's excellent Escalating Density Training, in your 15 min. blocks, once you get 70reps inside a set, pretty much time to up the weight. What more is there to volume than that? Over the weekend, talking with Suleiman Al-Sabah about our mutual pressing goals, Al encouraged me again to think about doing "lots of reps" and reminded me of Kenneth Jay's part of the RKC manual on building strength. So i went to have a bit of a re-read.

The rationale for volume by rep: Kenneth talks about the need to do lots and lots of reps at a weight that can be readily sustained for lots and lots of reps to build up the neurological patterns of what that move is. The caveat to this volume, of course, is that you have to know what the correct form is to be repeated. See that RKC instructor.

Assuming that instruction has taken place, the rationale here for upping volume as half the strategy to strength is that this repetition neurologically groves the pattern of performance for building up the weight. To this end, Kenneth has Low Volume and High Volume days: lost of reps at lighter weight for grooving the pattern vs fewer (perfect) reps at higher weights to develop load.

Patterning is important. I've been focusing on the importance of patterning within z health practice - in terms of healing movement patterns, and taking those patterns from the level of conscious effort to unconscious habit. Over the weekend, i'd decided to focus just on my suitcase dead-lift form with KB's, using the EDT 15 min approach: the sDL's for the first exercise; floor presses for the second. For the sDL's I used a weight about half of what i usually use for such sets, just to focus on rep quality. The main points of concern, like that front squat for hitting the target meant correct head and eye position throughout the move, correct knee position, correct hip hinge, correct butt backness, and doing all this with bone ryhthmn. That's a lot to do. The cool thing that happened was that when everything was firing together, the rep simply felt better: more effective, more efficient, like all the parts working as one thing rather than as a bunch of joints and muscles trying to achieve something. Sadly by the time i was actually finished the 15 mins, and the sets of 5 reps were starting to really connect, (a) the time was up but (b) i was just starting to feel fatigued. Good time to stop, right? And keen desire to do it again. Oh, and i felt that workout the next day, too.

It's funny how when you need to hear something, you keep hearing it over and over, eh? At least i find this. It's like the opposite of a nightmare where you keep having the same monster, only bigger, until you stop turn around and look at the monster and say "can i help you?"

An Example of Rep Volume in Action. The Sneaky sneaky Way of the RKC. It was in the afternoon, after this morning workout, that i had the meet with Al and his recommendation of "lots of reps" and a reread of Kenneth Jay. And in rereading that section, i recollected one of the most profound experiences of the RKC cert: connecting with the swing. Indeed, i had a revelation of what the hardstyle swing form was, compared to how i'd interpreted and executed previous instruction. I felt i *got it* from "firing the lats" to getting the energy down into the ground. it was ah ha, ah ha, ah ha. I left the cert feeling pretty good about that swing, and could hardly wait to share these refinements with others.

How did that happen? Repeated instruction i'd thought and such attention on form over several days, but - i see it all now - the other key ingredient: lots and lost of reps. LOTS. Sneaky sneaky. Every 20mins over three days a timer went off and we were doing swings. And those were just the regularly scheduled ones. Any opportunity for pause was filled with swings, using a bell weight that enabled a perfect rep from first to last. So combine that volume with constant supervision to tweak and correct form, yes we'd better leave with a dang good sense of the swing. The other day i was quietly delighted when i was demo'ing a swing, the trainee laughed. I asked why. He said "well it's so right - the swing - that's what it's supposed to look like." With the instruction, it's the reps, isn't it.

Putting it together: More Reps Are Alright, Jack.

It's taken me till today to put it together that it's just this type of volume with focus on form that, ya, does embed the move in the body. And more, it does provide the basis for increasing the load, just as KJ and Pavel have said. As proof positive, half way through the cert, with the encouragement of team assistant instructor Lynda Angeles, i was double swinging 24s with proper form. That effort with that load would not have been possible - it was certainly not imaginable - prior to this halfway point in the three days of swings marvelous swings.

The take away at least for this first step towards a perfect rep, of Hitting the Target, is indeed doing what it takes to get in the volume of reps. This is not using a sissy weight. Pavel would not have let us get away with this during the RKC, but as KJ says in the RKC manual talking about presses: using a weight you can do for 5-15 reps, and if you're doing 15 reps, your high volume day better be 200/side.

I used to think of light days as just a way to keep effort alive and not burn out from higher work volume. Ho hum. I now find myself energized and looking forward to these high volume lighter weight days as an opportunity to have that form *click* in those moves where i've had instruction, and can monitor myself to feel that connection.

Hope if you've had questions about the role of volume of reps, these reflections might help you too experience where the path to the perfect rep, after instruction and knowledge of proper form, is aided immensely by rep volume.

Note: do look at Mike's comments below on fascial adaptation - and the recommendation to change up trunk positions for HIGH volume (thanks Mike).

Book Plug: Kenneth Jay in the New Year.

Book Plug: Kenneth Jay in the New Year.

Now if you don't have an RKC certification manual to read up on Kenneth's approach to the press, fear not. A book is coming in the new year to focus says Kenneth on, perhaps not surprisingly, the perfection of the press, the pistol and the pull up. In the meantime, happy repping.

update: the quest for the perfect strength rep through volume continues, charting the course here. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

One of the first things that struck me in reading Pavel's work like Enter the

Kettlebell is the emphasis on "the perfect rep." Don't go to failure; don't do so many reps that form goes to hell. Stay fresh. Make every rep perfect.

Kettlebell is the emphasis on "the perfect rep." Don't go to failure; don't do so many reps that form goes to hell. Stay fresh. Make every rep perfect.But what is the "perfect rep"? And how do we know if we have one?

This may not be your experience, but i've interpreted this "perfect rep" thing as getting the form right mechanically, and executing with the correct weight for the correct sets and moving on, eg doing the ladders for ETK's ROP. Upon reflection, though, that progression doesn't sound much like an experience of "perfection," does it? Sure one feels good after doing the workouts, and yes progress most emphatically occurs. But is it "perfection?" And why is experiencing perfection so important? would i know it if i did encounter it?

Some time ago i wrote about how seeing Will Williams doing the kettlebell front squat - in particular the breathing to go with that move - stopped me in my tracks as seeming effortless and perfect. I'd described it as what i'd understood art to be about, when a move goes from the mechanistic to the graceful.

The parts of perfection. Last week or so, looking at the kettlebell front squat, i came back to the front squat, going over how zhealth breaks down the concept of efficient movement into four parts that seems to be a recipe for the perfect rep:

- perfect form - hitting the target

- dynamic postural alignment.

- synchronized respiration

- balance tension and relaxation

What's been hitting me of late as a key feature of even getting into step one - hitting the target/perfect form - is volume by repetition. In other words, tons of reps. Which means lighter weights.

What's a Rep, really? Generally speaking, i've thought of reps as simply reps within a set, and that volume is just whatever you get from the total reps x mass for a particular workout. Increasing reps, especially when focusing on strength, has seemed just the wrong way to think about it, too: loads of reps is endurance strength, not power strength, heh we want POWER to PRESS. And it seems many protocols for strength reinforce this. For instance, in Charles Staley's excellent Escalating Density Training, in your 15 min. blocks, once you get 70reps inside a set, pretty much time to up the weight. What more is there to volume than that? Over the weekend, talking with Suleiman Al-Sabah about our mutual pressing goals, Al encouraged me again to think about doing "lots of reps" and reminded me of Kenneth Jay's part of the RKC manual on building strength. So i went to have a bit of a re-read.

The rationale for volume by rep: Kenneth talks about the need to do lots and lots of reps at a weight that can be readily sustained for lots and lots of reps to build up the neurological patterns of what that move is. The caveat to this volume, of course, is that you have to know what the correct form is to be repeated. See that RKC instructor.

Assuming that instruction has taken place, the rationale here for upping volume as half the strategy to strength is that this repetition neurologically groves the pattern of performance for building up the weight. To this end, Kenneth has Low Volume and High Volume days: lost of reps at lighter weight for grooving the pattern vs fewer (perfect) reps at higher weights to develop load.

Patterning is important. I've been focusing on the importance of patterning within z health practice - in terms of healing movement patterns, and taking those patterns from the level of conscious effort to unconscious habit. Over the weekend, i'd decided to focus just on my suitcase dead-lift form with KB's, using the EDT 15 min approach: the sDL's for the first exercise; floor presses for the second. For the sDL's I used a weight about half of what i usually use for such sets, just to focus on rep quality. The main points of concern, like that front squat for hitting the target meant correct head and eye position throughout the move, correct knee position, correct hip hinge, correct butt backness, and doing all this with bone ryhthmn. That's a lot to do. The cool thing that happened was that when everything was firing together, the rep simply felt better: more effective, more efficient, like all the parts working as one thing rather than as a bunch of joints and muscles trying to achieve something. Sadly by the time i was actually finished the 15 mins, and the sets of 5 reps were starting to really connect, (a) the time was up but (b) i was just starting to feel fatigued. Good time to stop, right? And keen desire to do it again. Oh, and i felt that workout the next day, too.

It's funny how when you need to hear something, you keep hearing it over and over, eh? At least i find this. It's like the opposite of a nightmare where you keep having the same monster, only bigger, until you stop turn around and look at the monster and say "can i help you?"

An Example of Rep Volume in Action. The Sneaky sneaky Way of the RKC. It was in the afternoon, after this morning workout, that i had the meet with Al and his recommendation of "lots of reps" and a reread of Kenneth Jay. And in rereading that section, i recollected one of the most profound experiences of the RKC cert: connecting with the swing. Indeed, i had a revelation of what the hardstyle swing form was, compared to how i'd interpreted and executed previous instruction. I felt i *got it* from "firing the lats" to getting the energy down into the ground. it was ah ha, ah ha, ah ha. I left the cert feeling pretty good about that swing, and could hardly wait to share these refinements with others.

How did that happen? Repeated instruction i'd thought and such attention on form over several days, but - i see it all now - the other key ingredient: lots and lost of reps. LOTS. Sneaky sneaky. Every 20mins over three days a timer went off and we were doing swings. And those were just the regularly scheduled ones. Any opportunity for pause was filled with swings, using a bell weight that enabled a perfect rep from first to last. So combine that volume with constant supervision to tweak and correct form, yes we'd better leave with a dang good sense of the swing. The other day i was quietly delighted when i was demo'ing a swing, the trainee laughed. I asked why. He said "well it's so right - the swing - that's what it's supposed to look like." With the instruction, it's the reps, isn't it.

Putting it together: More Reps Are Alright, Jack.

It's taken me till today to put it together that it's just this type of volume with focus on form that, ya, does embed the move in the body. And more, it does provide the basis for increasing the load, just as KJ and Pavel have said. As proof positive, half way through the cert, with the encouragement of team assistant instructor Lynda Angeles, i was double swinging 24s with proper form. That effort with that load would not have been possible - it was certainly not imaginable - prior to this halfway point in the three days of swings marvelous swings.

The take away at least for this first step towards a perfect rep, of Hitting the Target, is indeed doing what it takes to get in the volume of reps. This is not using a sissy weight. Pavel would not have let us get away with this during the RKC, but as KJ says in the RKC manual talking about presses: using a weight you can do for 5-15 reps, and if you're doing 15 reps, your high volume day better be 200/side.

I used to think of light days as just a way to keep effort alive and not burn out from higher work volume. Ho hum. I now find myself energized and looking forward to these high volume lighter weight days as an opportunity to have that form *click* in those moves where i've had instruction, and can monitor myself to feel that connection.

Hope if you've had questions about the role of volume of reps, these reflections might help you too experience where the path to the perfect rep, after instruction and knowledge of proper form, is aided immensely by rep volume.

Note: do look at Mike's comments below on fascial adaptation - and the recommendation to change up trunk positions for HIGH volume (thanks Mike).

Book Plug: Kenneth Jay in the New Year.

Book Plug: Kenneth Jay in the New Year. Now if you don't have an RKC certification manual to read up on Kenneth's approach to the press, fear not. A book is coming in the new year to focus says Kenneth on, perhaps not surprisingly, the perfection of the press, the pistol and the pull up. In the meantime, happy repping.

update: the quest for the perfect strength rep through volume continues, charting the course here. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

perfect rep,

strength,

volume,

work out,

workout

Friday, October 10, 2008

How many repetitions should i do of this mobility drill?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Since starting to do Z training with folks, i get asked "how many times should i do this drill?" or "how frequently do i need to do that drill."

The cool thing about these Z drills - dynamic joint mobility - is that they are not just moving a joint through its range of motion to keep it healthy, these drills are hitting the thousands and thousands of mechanoreceptors around the joints, and adapting to those messages, as in the all pervasive principle of specificity (SAID). That's one.

The cool thing about these Z drills - dynamic joint mobility - is that they are not just moving a joint through its range of motion to keep it healthy, these drills are hitting the thousands and thousands of mechanoreceptors around the joints, and adapting to those messages, as in the all pervasive principle of specificity (SAID). That's one.

Another one is what Courtney Neupert has been telling me about the application of Wolff's Law, or that bone and tissue get reshaped based on the load/stresses placed upon them, all part of the "continuous cycle of osteoclastic/osteoblastic activity - old bone gets eaten up while new bone tissue is formed. " And how that new bone is formed responds to these new patterns. Likewise, Courtney reminds me, tissue. That adaptation can result in hypertrophy (a good thing) or tight shoulders (not so good), all adaptations to load.

So that's SAID and Wolff, but there's also another, which doesn't seem to have a punchy name or acronym. It's called "motor learning" and back in 67 Fitts and Posner proposed three stages for motor learning: cognitive, associative and autonomous. Within 1000 reps one is still learning a skill, having to bring conscious (cognitive) attention to it. Within 1000 - 10,000 and beyond, one is making fewer mistakes, is aware of them, knows how to correct them. By 100 thousand to 300 hundred thousand, one can perform a move without thinking about it - autonomously.

So let's go back to that question of how frequently one should be practicing a joint mobility move.

We know that with SAID, we adapt readily to imposed demand, and that with Wolff's Law, repeating those loading patterns re-builds us according to these new patterns. With these effects, we'll want to get into practicing these SAID/Wolff patterns perfectly. And we know with motor learning, it takes about 1000 reps just to learn that pattern, and tens of thousands to perform it well.

Therefore, repetitions to remodel (and counteact other imperfec t repetitions going on in our long standing autonomous actions like walking) need to be high, and repetitions just to learn the move also need to be high.

t repetitions going on in our long standing autonomous actions like walking) need to be high, and repetitions just to learn the move also need to be high.

If you're a westerner, for instance, who's learned to use chopsticks as an adult, think of how many openings and closings of the sticks it may have taken just to have gotten the hang of it, and ask yourself if you're at the associative stage yet or truly autonomous where using these is a comfy and thought-less as using a fork.

So, in answer to the question of how frequently one should perform a drill, an answer may be "as frequently as you want," with the understanding that given the numbers of repetitions necessary to learn, repattern and remodel, the more perfect reps, the more often, the faster the desired change will be effected.

The key marker here is perfect rep: do a set for as many reps as can be done perfectly (maybe 3-5) then pause, redo. Better to do many times a day than all at once and fall into poor form, since it's that form that is creating what is learned and the pattern of the adaptation. Getting to the perfect rep faster to optimize that learning is another reason to see a trainer to tune your approach. You can find an international list of Z trainers on the Z site. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

The cool thing about these Z drills - dynamic joint mobility - is that they are not just moving a joint through its range of motion to keep it healthy, these drills are hitting the thousands and thousands of mechanoreceptors around the joints, and adapting to those messages, as in the all pervasive principle of specificity (SAID). That's one.

The cool thing about these Z drills - dynamic joint mobility - is that they are not just moving a joint through its range of motion to keep it healthy, these drills are hitting the thousands and thousands of mechanoreceptors around the joints, and adapting to those messages, as in the all pervasive principle of specificity (SAID). That's one.Another one is what Courtney Neupert has been telling me about the application of Wolff's Law, or that bone and tissue get reshaped based on the load/stresses placed upon them, all part of the "continuous cycle of osteoclastic/osteoblastic activity - old bone gets eaten up while new bone tissue is formed. " And how that new bone is formed responds to these new patterns. Likewise, Courtney reminds me, tissue. That adaptation can result in hypertrophy (a good thing) or tight shoulders (not so good), all adaptations to load.

So that's SAID and Wolff, but there's also another, which doesn't seem to have a punchy name or acronym. It's called "motor learning" and back in 67 Fitts and Posner proposed three stages for motor learning: cognitive, associative and autonomous. Within 1000 reps one is still learning a skill, having to bring conscious (cognitive) attention to it. Within 1000 - 10,000 and beyond, one is making fewer mistakes, is aware of them, knows how to correct them. By 100 thousand to 300 hundred thousand, one can perform a move without thinking about it - autonomously.

So let's go back to that question of how frequently one should be practicing a joint mobility move.

We know that with SAID, we adapt readily to imposed demand, and that with Wolff's Law, repeating those loading patterns re-builds us according to these new patterns. With these effects, we'll want to get into practicing these SAID/Wolff patterns perfectly. And we know with motor learning, it takes about 1000 reps just to learn that pattern, and tens of thousands to perform it well.

Therefore, repetitions to remodel (and counteact other imperfec

t repetitions going on in our long standing autonomous actions like walking) need to be high, and repetitions just to learn the move also need to be high.

t repetitions going on in our long standing autonomous actions like walking) need to be high, and repetitions just to learn the move also need to be high.If you're a westerner, for instance, who's learned to use chopsticks as an adult, think of how many openings and closings of the sticks it may have taken just to have gotten the hang of it, and ask yourself if you're at the associative stage yet or truly autonomous where using these is a comfy and thought-less as using a fork.

The key marker here is perfect rep: do a set for as many reps as can be done perfectly (maybe 3-5) then pause, redo. Better to do many times a day than all at once and fall into poor form, since it's that form that is creating what is learned and the pattern of the adaptation. Getting to the perfect rep faster to optimize that learning is another reason to see a trainer to tune your approach. You can find an international list of Z trainers on the Z site. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

repetition,

work out,

workout,

z-health,

zhealth

Monday, September 8, 2008

Why Attend the Minnesota ZHealth Workshop: move better, feel better - really (a workshop preview)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Want to last longer, move better, reduce pain? At the end of october - in fact, that's halloween (Oct. 31) to Nov 2 - Dragon Door is hosting a Z-Health workshop called " Z-Health

Want to last longer, move better, reduce pain? At the end of october - in fact, that's halloween (Oct. 31) to Nov 2 - Dragon Door is hosting a Z-Health workshop called " Z-Health

The Essential Secrets of Elite Performance" for Athletes. Athletes is a term defined broadly: if you move, and want to improve your movement - your athletic effort - you're an athlete.

Why would you want to attend this workshop? There's a couple of big reasons:

(1) If you're an athlete who suffers from any kind of ache, tweak or out and out pain, and have repeatedly hit the manual therapists' offices - whether chiro, massage or similar, the approach presented in ZHealth (or Z-Health or Z Health) will help. That's a bold claim. It's true and i'll come back to it.

(2) If you're an athlete who's hit a plateau, you'll learn skills that will help you tune your performance in what are likely very new ways - unless you're already working with a trainer certified in the Z approach that will help you move past your plateau.

(3) if you're an athlete who needs good hand/eye coordination for your sport, believe it or not, you'll improve it.

(4) If you're an athlete learning a new sport or have been playing a particular sport for awhile, the workshop will help you move with more efficiency. More efficiency means more power, speed - more of what's good for your game. The same goes for whether you're a powerlifter, kettlebell'er or hockey player.

You may say, ok, those sound like incremental improvements. So what?

On the one hand, the answer might be well, increments are what it's all about in sport: in the recent olympics, the difference between a world and olympic record in the 200m men's sprint was 2/10ths of a second. it took almost a generation to beat that record, too. You may say well you're not competing at that kind of elite level; those kind of increments don't mean much to you.

OK. If getting better measurable gains in your activity is not important to you, that's fine. For instance, you mayn't care that you can walk your circuit faster; you just want to keep doing it.

So therefore, on the other hand, that's the other rationale for improving efficiency: improving function while reducing wear and tear on the body. If we move with more efficiency, we're using our bodies more effectively. That means less energy is put into that movement, which means we have more energy for other things. Likewise, that efficiency means better use of our limited resource - ourselves - which means fewer problems over the long haul.

A Stitch in Time Saves Nine

One of the things we learn about in human physiology is that we're internally extremely well connected - a tweak that starts in the foot can effect the knee, can effect the hip, can trigger the back, can bug the shoulder, can screw up the jaw, can hurt the head. The cumulative effect of these little things can mean at the least less effective, efficient movement and at the worst means a whole host of pain, and a set up for problems like injuries in the movements to come.

The z approach takes this science of our wiring and shows us how to tune our movement to create the clearest path, the freest signal through that wiring so that we can work as effectively as possible. That efficiency means better performance, reduced pain. It's freaky how these things connect, and how quickly the effect can be demonstrated.

The Missing Manual

One of the biggest drags about us is that we don't come with The Manual.

I used to work a lot on motorcycles - this was necessary as i could only afford ones that were made a decade or more before the period in which i was riding them, and so, that telling you something about my finances, i had to be able to maintain them. One of the best resources for this up keep was (a) canadian tire, home of many parts that could be jury-rigged into working and (b) clymer manuals on how these things fit together - both the mechanicals and the all-important electrics. Without these manuals, hacking around the bike to try to tune it was just guess work. If it worked, it was often more luck than knowledge.

We don't come with Clymers. Netter's Anatomy and Guyton and Hall's Physiology while great texts on body parts and discrete physical systems, ain't great when it comes to seeing how, to put it loosely, the mechanical interacts with the electrics.

Without such a manual, what we often do in our own training, especially those of us who do not have coaches, is our best guess hacks. We read the articles, maybe follow some forums, watch friends, and try to put together an effective approach to get results, from getting the right gear to applying "correct" form. But how do we know what we're doing *is* actually right? is actually good for us? We're extremely complex, highly adaptive systems. We take tons of abuse, from poor eating to high heel shoes and keep functioning. So sometimes it's hard to tell if what we're doing is wrong - especially if we seem to be making progress. But at what cost progress? Perhaps if you're making loads of gains and are completely pain-free (either during or apart from your activity), you've lucked out and are operating optimally. Way to go. For the rest of us, well, there's this tension we get in the neck, or the back kinda aches, or sometimes when we walk our knee hurts. Pavel has this comment on his seminar with Charles Staley "Put up your hands anyone who's had a shoulder injury. Anyone who hasn't put up their hands, can't"

Anyone who's been in pain, and been helped out of it knows how much better their activities or daily lives are. For some of us, we go to manual therapies, and feel great for a time once we're off the table. For some, that treatment's enough. For many of us, we have to keep going back to get that release.

For all of us in such tweaked categories, getting a manual to deal with these tweaks proactively can make a world of difference to our performance - on and off the field; in and out of the gym.

Demystifying Movement

In the Z approach, athletes get a broader view of movement than muscle. After all, we have bones, muscles, nerves, but we also have sensory and perceptual functions or various systems that maintain those bones muscles and nerves in space. Without these we couldn't stay upright, little own move. The Z approach takes each of these components into account when talking about tuning movement.

Some folks think that Z is about joint mobility: that its thing is just to focus on moving the bendy bits instead of manipulating muscles, like other folks do.

In my experience of Z the answer is yes and no. Yes, the initial approach (Day 1 of the workshop, R Phase focus) is HUGE on getting full range of motion around joints, but the focus on joints is there as a powerful means to an end. The real meat and potatoes of the this initial phase is about what's happening around those joints with our nervous system, particularly with mechanoreceptors. Joints have more of these awareness detectors than any other part of the body. If one part of the body is having issues with its reception, the ENTIRE rest of the body responds. You'll see a demo that shows a problem with a thumb - no pain, but a less than fully mobile joint - will substantially, hugely shut down the ability of the hamstrings to generate force, but how freeing up that thumb joint will bring that strength back. That improvement in strength had nothing to do with building mass; it had to do with improving the signal path from a seemingly unrelated joint back to the brain - to give the all clear for that joint.

Bottom line of R: decreased joint mobility (a joint that cannot move through full range of motion), decreased strength; increased mobility, increased strength.

In Day 2 with I phase, the focus moves from the joints' relation to movement into how our visual and vestibular systems - balance, eye tracking and so on effect movement.

The S part of the workshop begins to put these components together into movement practice for coordinated benefit.

THE GOODS

The workshop promo uses terms like "massive" development of power and "immediate" strength gains. These sound very much too good to be true, don't they? And (to me, unfortunately) the workshop also talks about "revealing secrets" to making these gains.

For the Less Trained. The thing is, if you haven't worked with a coach before ANY good coach will help you improve your performance - likely immediately. And if you haven't worked with a coach before, they may even break your current personal best in one session. So i'm not too moved by such claims. So on the grossest level, if you take this seminar you will definitely learn stuff to improve your performance, and you will see benefits right away. But what differentiates this approach from perhaps others is the longer haul: there are many many carry over effects of the whole Z approach that go beyond sport specific training.

If you learn how to squat right, for instance, you learn how to do this one activity well. If, however, you learn how to stand in balance on your bones, using as little energy as possible to hold a "long" spine, you have a foundation for effective powerful movement in any movement/activity (on day 3, if you're a kettlebeller, ask about "femur snap rather than hip snap" in the swing/snatch).

For the More Coached/Trained. If you have worked with coaches before, or do so right now, then you know how precious any gains can be. If your coaching/training has focused on mainly muscle work, it doesn't take a big leap of the imagination to get that if you can bring on board the other systems of the body like proprioception, like the vestibular and visual systems, that you're going to do better, harmonizing more of what the body has to offer to improve performance. Check out Mike T Nelson's posts about deadlift improvements with Z approaches for more.

For Those With Pain or Injury. If you've had an injury or are coping with one now, you'll know how valuable it can be to get out of pain so you can get back to your training. You may see a specialist to treat your ills and feel great while that happens. But have you asked yourself why do you have to keep going back to feel well? Do you believe that you will have to keep going to feel well? Would you like to explore the options of how you could take care of yourself such that you could get out of the treatment cycle?

If you are in pain, and would like that attended, may i recommend booking an appointment during the weekend with Dr. Cobb who will be delivering the workshop? He can assess and point you to a proactive plan for your own well being. It's worth it.

IN SUM

If you are keen to make your body last as long as possible pain free, running effectively, and efficiently, and if you want to improve your athletic performance, the skills you'll learn over these three days will literally last a life time.

Note for Instructors: if you're a trainer and want to learn how to provide these kinds of techniques for your clients, as well as how to do assessments of performance, you may want to consider taking in a Z-Health certification course rather than this workshop (here's a review of my experience with the first z-health cert, r-phase). Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Want to last longer, move better, reduce pain? At the end of october - in fact, that's halloween (Oct. 31) to Nov 2 - Dragon Door is hosting a Z-Health workshop called " Z-Health

Want to last longer, move better, reduce pain? At the end of october - in fact, that's halloween (Oct. 31) to Nov 2 - Dragon Door is hosting a Z-Health workshop called " Z-HealthThe Essential Secrets of Elite Performance" for Athletes. Athletes is a term defined broadly: if you move, and want to improve your movement - your athletic effort - you're an athlete.

Why would you want to attend this workshop? There's a couple of big reasons:

(1) If you're an athlete who suffers from any kind of ache, tweak or out and out pain, and have repeatedly hit the manual therapists' offices - whether chiro, massage or similar, the approach presented in ZHealth (or Z-Health or Z Health) will help. That's a bold claim. It's true and i'll come back to it.

(2) If you're an athlete who's hit a plateau, you'll learn skills that will help you tune your performance in what are likely very new ways - unless you're already working with a trainer certified in the Z approach that will help you move past your plateau.

(3) if you're an athlete who needs good hand/eye coordination for your sport, believe it or not, you'll improve it.

(4) If you're an athlete learning a new sport or have been playing a particular sport for awhile, the workshop will help you move with more efficiency. More efficiency means more power, speed - more of what's good for your game. The same goes for whether you're a powerlifter, kettlebell'er or hockey player.

You may say, ok, those sound like incremental improvements. So what?

On the one hand, the answer might be well, increments are what it's all about in sport: in the recent olympics, the difference between a world and olympic record in the 200m men's sprint was 2/10ths of a second. it took almost a generation to beat that record, too. You may say well you're not competing at that kind of elite level; those kind of increments don't mean much to you.

OK. If getting better measurable gains in your activity is not important to you, that's fine. For instance, you mayn't care that you can walk your circuit faster; you just want to keep doing it.

So therefore, on the other hand, that's the other rationale for improving efficiency: improving function while reducing wear and tear on the body. If we move with more efficiency, we're using our bodies more effectively. That means less energy is put into that movement, which means we have more energy for other things. Likewise, that efficiency means better use of our limited resource - ourselves - which means fewer problems over the long haul.

A Stitch in Time Saves Nine

One of the things we learn about in human physiology is that we're internally extremely well connected - a tweak that starts in the foot can effect the knee, can effect the hip, can trigger the back, can bug the shoulder, can screw up the jaw, can hurt the head. The cumulative effect of these little things can mean at the least less effective, efficient movement and at the worst means a whole host of pain, and a set up for problems like injuries in the movements to come.

The z approach takes this science of our wiring and shows us how to tune our movement to create the clearest path, the freest signal through that wiring so that we can work as effectively as possible. That efficiency means better performance, reduced pain. It's freaky how these things connect, and how quickly the effect can be demonstrated.

The Missing Manual

One of the biggest drags about us is that we don't come with The Manual.

I used to work a lot on motorcycles - this was necessary as i could only afford ones that were made a decade or more before the period in which i was riding them, and so, that telling you something about my finances, i had to be able to maintain them. One of the best resources for this up keep was (a) canadian tire, home of many parts that could be jury-rigged into working and (b) clymer manuals on how these things fit together - both the mechanicals and the all-important electrics. Without these manuals, hacking around the bike to try to tune it was just guess work. If it worked, it was often more luck than knowledge.

We don't come with Clymers. Netter's Anatomy and Guyton and Hall's Physiology while great texts on body parts and discrete physical systems, ain't great when it comes to seeing how, to put it loosely, the mechanical interacts with the electrics.

Without such a manual, what we often do in our own training, especially those of us who do not have coaches, is our best guess hacks. We read the articles, maybe follow some forums, watch friends, and try to put together an effective approach to get results, from getting the right gear to applying "correct" form. But how do we know what we're doing *is* actually right? is actually good for us? We're extremely complex, highly adaptive systems. We take tons of abuse, from poor eating to high heel shoes and keep functioning. So sometimes it's hard to tell if what we're doing is wrong - especially if we seem to be making progress. But at what cost progress? Perhaps if you're making loads of gains and are completely pain-free (either during or apart from your activity), you've lucked out and are operating optimally. Way to go. For the rest of us, well, there's this tension we get in the neck, or the back kinda aches, or sometimes when we walk our knee hurts. Pavel has this comment on his seminar with Charles Staley "Put up your hands anyone who's had a shoulder injury. Anyone who hasn't put up their hands, can't"

Anyone who's been in pain, and been helped out of it knows how much better their activities or daily lives are. For some of us, we go to manual therapies, and feel great for a time once we're off the table. For some, that treatment's enough. For many of us, we have to keep going back to get that release.

For all of us in such tweaked categories, getting a manual to deal with these tweaks proactively can make a world of difference to our performance - on and off the field; in and out of the gym.

Demystifying Movement

In the Z approach, athletes get a broader view of movement than muscle. After all, we have bones, muscles, nerves, but we also have sensory and perceptual functions or various systems that maintain those bones muscles and nerves in space. Without these we couldn't stay upright, little own move. The Z approach takes each of these components into account when talking about tuning movement.

Some folks think that Z is about joint mobility: that its thing is just to focus on moving the bendy bits instead of manipulating muscles, like other folks do.

In my experience of Z the answer is yes and no. Yes, the initial approach (Day 1 of the workshop, R Phase focus) is HUGE on getting full range of motion around joints, but the focus on joints is there as a powerful means to an end. The real meat and potatoes of the this initial phase is about what's happening around those joints with our nervous system, particularly with mechanoreceptors. Joints have more of these awareness detectors than any other part of the body. If one part of the body is having issues with its reception, the ENTIRE rest of the body responds. You'll see a demo that shows a problem with a thumb - no pain, but a less than fully mobile joint - will substantially, hugely shut down the ability of the hamstrings to generate force, but how freeing up that thumb joint will bring that strength back. That improvement in strength had nothing to do with building mass; it had to do with improving the signal path from a seemingly unrelated joint back to the brain - to give the all clear for that joint.

Bottom line of R: decreased joint mobility (a joint that cannot move through full range of motion), decreased strength; increased mobility, increased strength.

In Day 2 with I phase, the focus moves from the joints' relation to movement into how our visual and vestibular systems - balance, eye tracking and so on effect movement.

The S part of the workshop begins to put these components together into movement practice for coordinated benefit.

THE GOODS

The workshop promo uses terms like "massive" development of power and "immediate" strength gains. These sound very much too good to be true, don't they? And (to me, unfortunately) the workshop also talks about "revealing secrets" to making these gains.

For the Less Trained. The thing is, if you haven't worked with a coach before ANY good coach will help you improve your performance - likely immediately. And if you haven't worked with a coach before, they may even break your current personal best in one session. So i'm not too moved by such claims. So on the grossest level, if you take this seminar you will definitely learn stuff to improve your performance, and you will see benefits right away. But what differentiates this approach from perhaps others is the longer haul: there are many many carry over effects of the whole Z approach that go beyond sport specific training.

If you learn how to squat right, for instance, you learn how to do this one activity well. If, however, you learn how to stand in balance on your bones, using as little energy as possible to hold a "long" spine, you have a foundation for effective powerful movement in any movement/activity (on day 3, if you're a kettlebeller, ask about "femur snap rather than hip snap" in the swing/snatch).

For the More Coached/Trained. If you have worked with coaches before, or do so right now, then you know how precious any gains can be. If your coaching/training has focused on mainly muscle work, it doesn't take a big leap of the imagination to get that if you can bring on board the other systems of the body like proprioception, like the vestibular and visual systems, that you're going to do better, harmonizing more of what the body has to offer to improve performance. Check out Mike T Nelson's posts about deadlift improvements with Z approaches for more.

For Those With Pain or Injury. If you've had an injury or are coping with one now, you'll know how valuable it can be to get out of pain so you can get back to your training. You may see a specialist to treat your ills and feel great while that happens. But have you asked yourself why do you have to keep going back to feel well? Do you believe that you will have to keep going to feel well? Would you like to explore the options of how you could take care of yourself such that you could get out of the treatment cycle?

If you are in pain, and would like that attended, may i recommend booking an appointment during the weekend with Dr. Cobb who will be delivering the workshop? He can assess and point you to a proactive plan for your own well being. It's worth it.

IN SUM

If you are keen to make your body last as long as possible pain free, running effectively, and efficiently, and if you want to improve your athletic performance, the skills you'll learn over these three days will literally last a life time.

Note for Instructors: if you're a trainer and want to learn how to provide these kinds of techniques for your clients, as well as how to do assessments of performance, you may want to consider taking in a Z-Health certification course rather than this workshop (here's a review of my experience with the first z-health cert, r-phase). Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Monday, August 25, 2008

Increase the Weight and Challenge of your KB's: Kneel!

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Some have shown that if you want a cheap way to increase the weight of your upper body Kettlebell work, go "bottom's up": hold the handle so the butt of the bell is in the air, rather than hanging down. Here's another that can increase the effort on your presses, whether with dumbbells or kettlebells: kneel. If you want to challenge your stability as well as strength, genuflect.

Taking the legs out of the equation to induce more of an upper body challenge is not new: Pavel Tsatsouline in More Russian Kettlebell Challenges uses various seated presses; Mike Mahler does likewise at least once in most of his DVDs.

The difference is that these are seated variants, and kneeling is the kind of halfway house between standing and sitting; kneeling vs genuflecting provides even more opportunities for working balance and motion. In the CK-FMS, more about these challenges are taught as corrective strategies for mobility and stability.

But even without such study, you can give kneeling/genuflecting a try: you'll be surprised no doubt at how the bell you feel comfortably challenged pressing from your feet becomes impossible on one's knees.

This simple positional change adds a radical new dimension to one's training. I'm personally blown away by how an adaptation that costs nothing gives me a whole new way to practice familiar moves with a new perspective, as shown by Rif here

Give it a try. Let me know what you find.

Tweet

Follow @begin2dig

Taking the legs out of the equation to induce more of an upper body challenge is not new: Pavel Tsatsouline in More Russian Kettlebell Challenges uses various seated presses; Mike Mahler does likewise at least once in most of his DVDs.

The difference is that these are seated variants, and kneeling is the kind of halfway house between standing and sitting; kneeling vs genuflecting provides even more opportunities for working balance and motion. In the CK-FMS, more about these challenges are taught as corrective strategies for mobility and stability.

But even without such study, you can give kneeling/genuflecting a try: you'll be surprised no doubt at how the bell you feel comfortably challenged pressing from your feet becomes impossible on one's knees.

This simple positional change adds a radical new dimension to one's training. I'm personally blown away by how an adaptation that costs nothing gives me a whole new way to practice familiar moves with a new perspective, as shown by Rif here

Saturday, August 23, 2008

Pull Ups: How To Do Pull Ups Resources (Pull Ups 101)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

What muscles do pull ups work? How increase number of pull ups: with weights or reps? How achieve that first pull up? What's Pavel's Fighter Pull Up Program? What's the difference between a chin up and a pull up? These topics and more looked at in this post.

For many, the quest to perform a single pull up is a Big Deal. For gals especially, where are upper body strength is at a disadvantage relative to the males of the species, achieving a single body weight pull up is to have reached a critical pinnacle of success. Indeed, in the RKC School of Strength, a key test for men and women as Level 2 instructors is the single Tactical Pull Up: dead hang, pull up so neck touches the bar. Must be completed once, men and women alike.

Methods a Plenty. Fortunately, for something perceived to be such a mark of fitness accomplishment, there are almost as many methods to training to achieve a pull up as there are people blogging about pull ups. Just a reminder, the pull up and chin up are distinguished by the hand grip: the pull up is pronated (palms facing away); the chin up is supinated (palms facing).

The purpose of this post is to go over a few of the many resources where i've heard back from folks i trust to say they actually work.

The Prime Movers of the Pull Up. Before getting into technique, it's worth reviewing what's going on mechanically in the pull up: that can help focus on what we need to be working to make progress (excuse me if this is going over what are basics for you).

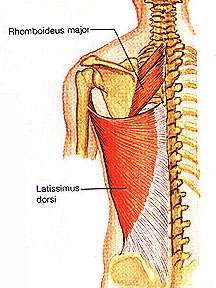

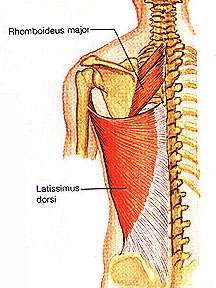

Some folks would look at the pull up and say that's arm work: need big biceps to pull yourself up. Indeed, pull ups can be very good for the biceps. The rear delts also come into play. Mainly, however, the pull up works the back. In particular it really works the Lats, or latissimus dorsi one of the largest muscles in the body. Some folks may be skeptical about focusing on the lats rather than the bi's for pull ups. Charles Staley motivates the comparison this way "if you load your bodyweight onto a bar, how many times can you curl it? I’m guessing 0."

Some folks would look at the pull up and say that's arm work: need big biceps to pull yourself up. Indeed, pull ups can be very good for the biceps. The rear delts also come into play. Mainly, however, the pull up works the back. In particular it really works the Lats, or latissimus dorsi one of the largest muscles in the body. Some folks may be skeptical about focusing on the lats rather than the bi's for pull ups. Charles Staley motivates the comparison this way "if you load your bodyweight onto a bar, how many times can you curl it? I’m guessing 0."

Why are the lats more vital than the biceps in the Pull Up? Let's take a sec to consider the connections of the muscles. The biceps for sure are elbow flexors. And yes, pulling UP means flexing the elbows. BUT the lats also enable the trunk to be pulled up via shoulder (or glenohumeral joint) extension. How does that work? The lat is like a big triangle of tough stretchy stuff that is nailed down along the spine from the middle of the back, just under the shoulder blade, right down into the butt at the sacrum. That's a lot of back. So the mid thoracic spine is one point on the triangle; the sacrum is the second, and the third is in the arm, on the "medial side of the intertubercular groove of the humerus"

BUT the lats also enable the trunk to be pulled up via shoulder (or glenohumeral joint) extension. How does that work? The lat is like a big triangle of tough stretchy stuff that is nailed down along the spine from the middle of the back, just under the shoulder blade, right down into the butt at the sacrum. That's a lot of back. So the mid thoracic spine is one point on the triangle; the sacrum is the second, and the third is in the arm, on the "medial side of the intertubercular groove of the humerus"

The lat connected in this way supports four movements of the shoulder joint: extension (movement of the humerus straight, posteriorly), bringing it across and in front of the body (adduction); internal rotation (putting your lower arm behind your back); bringing your arm up and around so that you can grab the opposite shoulder to the upraised arm (horizontal abduction).

So the biggie move of the lat in the pull up is to get that arm back down by your side. Remember, it's huge area is pulling from the mid back down to the butt, all focused on that single spot in the arm. That's a lot of reef.

Compare that amount of pulling area from the lats into the shoulder against the biceps into the elbow, and it's really no contest. Staley's visualization hits home: trying to biceps curl bodyweight (biceps focus in the pull up) vs pulling bodyweight (lat focus). Intriguingly, we also get an insight into why chin ups are "easier" than pull ups: with a chin up (supinated) grip, we have a more typical curl going, working flexors as well as biceps.

Thinking through the Movement. We can get in the way of our own pull up progress by focussing too much on the biceps and not enough on firing those massive lats. Below are a few techniques to visualize pulling from the lats. If the goal is to focus on the lats rather than biceps, a well known, powerful technique to focus muscle firing is visualization. Powerlifter Jerry Nicolas talks about doing a pull up imagining that the elbows connected to the sides by cables, so that when you're hanging from the bar, the cables are extended; getting up to the bar, the sides are reeling up the cable, raising your body. Charles Staley uses a similar visualization:

Aside: Contrasting Lat Pull Downs with Pull ups. Going deeper into not just what muscles are fired on the gross level, but on the micro level, some people wonder whether doing lat pull downs aren't the same as pull ups, except in reverse. The short answer is "no." Two quicky reasons: (1) hanging in space requires different neuro muscular adaptations (different numbers and patterns of muscle fibers recruited within the same muscle) than sitting on a bench and (2) based on Stuart McGill's research (see Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance) on how evil and unnatural sitting is for your back especially, do you *ever* want to do seated resistance work - of any kind?

Enough! Just tell me how to get up! So now that the muscle work is sussed, and the visualizations are worked out, how to get the physical work happening.

IF you can do One or More Pull Ups

Gold Standard: Clarence Bass describes Pavel Tsatsouline's Buddy Ladders. These are expanded in more detail as the Fighter Pull Up sequence (pdf only), also by PT. Each of these sequences is based on a ladder going up: do 1, pause. do 1, 2. pause. do 1,2,3 etc. This simple approach has been shown time and time again to have powerful effects.

Now, i have to say that i have plateaued with ladders at 7, so went looking for alternative approaches. Roland Fisher, a trainer in Alberta i really respect, pointed out a cool program in, yes, a Men's Health article by Mike Mejla, MS, CSCS. It provides some bench marks on when to add weight to body weight for increasing reps, for instance, that i'm finding very helpful.

Another approach that many RKC's have claimed super success: once you can do 7-10 reps, start adding weight, and start again. They have found that working with weights has let them, when going "naked" get rep ranges for which they have not trained.

These 4 approaches rather assume you can already do one pull up, but what if you can't? A number of both my male and female students haven't been able to get off the ground right off the bat, and that has kept them from thinking it's possible.

Getting to that First Pull Up

There are many tried and true strategies to get to that first pullup. One includes doing negatives. This is how i got my first pull up. With a negative, you find a way to get to the pullED up position, and then use muscle while going down. We are much stronger going eccentrically (using muscles streching out ) than concentrically (contracting). Negatives are a time proven way to help build up pull ups.

Another strategy is to use an appliance to help get up and down. A great appliance is stretch band. I personally like using Iron Woody bands: they're affordable and durable.

Here's an example vid of how to sling bands to a pull up bar:

Alternative Attachment of the band to the bar: as shown in the vids, some people just loop the band through itself around the bar - that uses up a lot of band and means generally you're using your knee in the band. You can change the resistance of the band by lengthening it. One way to do it is to use a big carabiner to attach the band to the bar. You can also set up some climbing webbing/tubing to the 'biner to get even more length and eliminate the biner. I like the biner when taking the band to the gym: means i can set it up and pack it up quickly.

One other strategy to get going, and a great use for a smith machine, are Floor Assisted Pull Ups. This approach also mean you're not using your complete body weight, but can increase the resistance (move your legs back or the bar up) as effort improves. Floor assisted work can also of course be combined with negatives.

One other strategy to get going, and a great use for a smith machine, are Floor Assisted Pull Ups. This approach also mean you're not using your complete body weight, but can increase the resistance (move your legs back or the bar up) as effort improves. Floor assisted work can also of course be combined with negatives.

Once a First Pull Up is achieved, Carter Schoffer also has an interesting pull up program mixing what might be called "raw" and assisted pull up work, where a multiple of the raw pull up is used to calculate numbers of assisted pull ups for sets.

Inspiration. If you would like some inspiration going for that first pull up, you may find it in these folks, men and women alike, who have done the Tactical Strength Challenge. My personal hero is Angela Craig, RKC, of the UK who has come in first internationally for the past two meets [1], [2], well ahead of many gals her junior.

And one more thing. Well three more: Head Position, Flexion/Extension and Bone Rhythm