Sunday, October 24, 2010

Unpacking a mystery: when shoulder pain may be all (or largely) in the wrist (a t-phase assessment story)

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Pavel tells the joke about asking people in a weight room "so those of you who have had a shoulder injury, raise your hands" - half the people raise their hands; the other half can't.

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

mc

Related Posts

Various types of shoulder issues are super common, and the usual go-to place is that the cause must be a rotator cuff tendon issue. But at least in my case, turns out it may be something very different: a muscle imbalance. That is, some muscles getting overworked with others getting underworked, resulting in other muscles not doing their jobs, and other muscles and associated tendons getting a bit worn out from having to do another muscle's job to pick up the slack. What's remarkable is how much immediate relief there can be once this issue is identified and actively addressed. So this is a bit of a story of unpacking that mystery through a lens that says always remember the site of pain mayn't be the source of pain.

Personal Case Study

A while ago i did a few posts about the latest work on tendonopathies and healing them, and a festival of posts on the amazing shoulder as a system in the body ( shoulder girdle part 1, gleno-humeral joint part 2), and then there was one about stopping reps in a set before they stopped us. These posts were largely motviated by my ongoing ache in my arm/shoulder. And i must say i was getting just a wee bit frustrated that i wasn't getting anywhere. This is the story of finally getting somewhere.

In the beginning: Seeing the MD. back in may/june the doc i first saw when my pain was at peak suggested what i had was a supraspinatus (top rotator cuff muscle) tendinitis. Ok.

Now i'm studying anatomy, and from what i could tell, all that muscle does is assist lifting the arm up to the side (like making airplane wings with ones arms). The things that hurt however were putting my coat on, when the arm reaches back to stick the arm into the jacket, and then when going the entire other way - crossing arms over to pull off a sweater. Ok, so maybe that's from a puffy supraspinatus getting jammed into the acromium of the shoulder (shown right) when the arm extends or internally rotates when abducting (emptying a pitcher). That seems pretty classic. And a week's worth of nsaids DID let me put my coat on again. So there seems to have been something going on there. But that wasn't all. Cuz it still hurt.

The Post MD Analysis, July 2010

In July, i'd asked a very competent movement scholar and chiropractic student to take a look at me, and we were rather flumoxed. He got as far as suggesting, based on loads of assessments, that perhaps it was lower trap related as doing some lower trap work seemed to bring some relief - he suggested that i spend some time with some drills focusing on lower trap work from Secrets of the Shoulder, which i did.

Time Passes - things shift/get worse. Intriguingly, the pain changed, but did not go away; my strength progress was bottoming out. My press was not only totally buggered on the left, the pain was getting triggered when doing my right press. Not good for a gal who wants to press a 24kg kettlebell for reps.

The other thing? Where it really seemed to hurt was at the top-ish of the arm. And then the pain radiated down into the biceps. Maybe supraspinatus pain refers into the arm, i wondered.

But here's another thing: both the insertion of the supraspinatus (the attachment point furthest away from the middle of the body) and the origin of the long head biceps tendon (the attachment point of the muscle closest to the middle of the body) are very close to each other. The supraspinatus inserts at the superior facet of greater tubercle (or tuberosity) of the humerus (at the top of the upper arm bone). The long head of the biceps brachii passes over a notch in the humerus to attach to the supraglenoid tubercle - a part of the surface of the scapula that the humerus abuts in the shoulder.

In other words the two tendons are almost right on top of each other, and both connect with with the upper arm/scapula, so if one's sore, perhaps the other is going to bloody feel it, too? Or perhaps they'll just be hard to discern from each other.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.

Why is this identification of tendon proximity important? It's going to play a role shortly.Indeed, reading about biceps tendinitis certainly seems similar to "overhead overuse" injuries for the supraspinatus rotator cuff. Reading about it also sounds pretty dam fatal: wear and tear; doom and gloom. And strengthening the the biceps doesn't seem to be the winner here.

So what we have here is pain in shoulder extension and external rotation and pain in shoulder flexion, adduction and internal rotation. Yuck. Easier to stay naked than put clothes on or off, but not functional, and not helpful athletically. Playing frisbee all summer was a great way mainly to keep my shoulder mobile-ish without load, but i more or less had to forget about my 24kg press work.

The Analysis Redux, Oct 2010

Now we come to the latest analysis this past week with a very experienced z-health movement performance specialist whom i'd been waiting to have an opportunity to see. 1st, we went over the issue, reviewing a detailed history (any stomach upset? any elbow issues? any neck pain? etc). Second, there was a look/test of some muscles between left and right sides.

What i had noticed only recently came to view here: my posterior delt was not firing fully - lots of squishy bits in it - compared to how well the right side was firing, the left lower posterior delt was like a deflated tire. That can't be good. Indeed see this post on muscle firing through the whole of the muscle for more. From here, we started to Assume the Postion(s) - the Positions of Pain and test these.

Assessment Process, close up. After setting some global baselines, we moved through many of the muscles of the shoulder, either offering them an assist or taking them out of the equation to see what helped or did not through those movements. By this careful process of elimination, we got down to a few interesting findings:

1) pain in the biceps: there's that biceps tendon going into the shoulder - address that, and guess what - pain HUGELY reduced.

2) help out the brachioradialis/extensors (esp carpi radialis perhaps) overlapping tendon/musle area, there's more relief (nerve work for the radial nerve included).

3) muscle test some of those extensors and there's squishy bits - get that fixed so the whole extensor is firing, more relief.

4) pay attention to the axilary nerve that fires the deltoids, and the posterior delt starts to come back on line (have some more work to do there but heck it's work i know how to do).

5) do a wee bit of hybrid minimal t-phase style kinesio taping around the long head bicpes tendon area, matched up with active dynamic joint mobility drills for the shoulder, elbow and extensors, and things start to simmer down

6) work out some of the fascial stickiness around the extenors with v.light hybrid t-phase fascial work

7) get some exercises for working the extensors in particular,

And ta da, muscles start to re-balance, pain be much more gone; i can press again.

How could this issue come to be?

It's often just a best guess with what causes anything, but one proferred explanation for my stuff especially with the wrist/finger extensors is that kettlebelling offers a lot of opportunities for loaded wrist/finger flexion, not so much for loaded wrist/finger extension work. As in anything, balance is important. So who knows? Perhaps when doing a ton of double kb work, i pushed my less strong side to follow with my stronger side and things went sufficiently out of whack to build up an inflamation and ongoing pain. This fits more of the facts than a supraspinatus diagnosis alone.

Rehab'ing

Beyond the above mentioned mobility and nerve drills, i'm doing some specific strength work. For the extensors i'm using two props: a mini jump stretch band with very light tension focusing on only enough load that i can get full to end range of motion wrist extension and wrist circles for the extension. I'm also using ironmind finger bands to practice finger extension reps. For mobility, i'm doing a lot of finger waves.

Master Class in Test/Re-assess.

This whole suit of components listed above stemming from this assessment was very much for me a master class in what we learn in z-health t-phase (about z-health): take a great history; test and retest EACH step of an analysis (i haven't detailed all the stuff that was tested that did not get a result); apply one's understanding of muscle interaction, muscle function and nerve interaction; check function to bring it back on line; when locked in, apply dynamic joint mobility and loaded dynamic joint mobility as appropriate.

Test, re-test continuosly. Analysis is a process. And as things change/improve, retesting and refining in rehab remains important.

Analysis is also a process that follows where the path leads: despite the fact that this kind of pain is supposed to be indicative of a SITS/rotator cuff injury, it may not be. I'm also intrigued to learn about how the extensors relate to balancing the shoulder in rotation. Not something that seems obvious taking a shoulder-only focus. Likewise that working the area of the biceps tendon can be so impacted by rotation when it itself is not a rotator - makes sense looking at how rotation may stretch it, but again that's following the path and testing - and also having some faith. I *knew* i felt pain through the biceps, but just never conencted this with the biceps tendon.

A note on pain and perfromance:

One of the effects of finding these muscle imbalances and nerve issues was an immediate and pretty signficiant improved range of motion. Like way - 15-20 degrees of extension in the shoulder that i didn't even know i had.

What this experience reiterates for me is that pain is a performance signal; that having pain reduces performance, and perhaps especially that optimizing what we need for performance not only reduces that pain signal but also, as a connected process, opens up performance. The two are intimitaley and it seems inextricably related.

As i've suggested before, pain it seems is just another performance inhibitor indicator like tight muscles that restrict range of motion can be. When we take time to work with a movement performance coach to walk through the process, work the problem, both relief and performance pour in. I know this all intellectually - it makes sense in terms of what we know neurologically - but from time to time a demonstration of same is a pretty vital reminder of these issues.

In my case, the focus was on identifying performance issues: squishy muscle bits in extensors; impingement of some kind around muscles/tendons; looking at strategies to help bring performance back on line, lots of active work. Et voila: pain significantly reduced.

Coda It's only been a week since i've had this assessment but the performance improvment (and consequent pain reduction) is legion in comparison to what it's been. I'm being very gentle with working back into arm and shoulder strength work, but that i can get into these ranges of motion sans pain/ROM issues is pretty fab after months of pain/limitation.

What seems to have happened is that there is a path of unpacking/unwinding a problem going on towards addressing it. What is exciting to me is that the movement principles i've been studying for the past two and a half years keep working - even for difficult cases. The nervous system is a remarkable thing.

It's rewarding to get to a place of really starting to see how the application of these principles continually opens up new opportunities to support healing without creating more pain first and with such immeidate effect.

Self-critique. I am also somewhat kicking myself for not working these patterns myself: nothing was really done in this assessment that i haven't been trained to do myself - that's the plus side. The down side is that i didn't take the time to work through this for myself. I remember moaning over the phone to one of the z-health master trainers how frustrated i'd been that i couldn't see a z-health solution to this problem, and his calm reply was "did you do all of the assessments"? i figured out that there were literally about 14 thousand possible combinations of assessments and that i guess i really hadn't. It's a good thing we're not our own healers, and i'll say again, everyone needs a coach.

And one more time: analysis is an iterative process. Sometimes it will take more than one hour to get to the heart of a gnarly problem. In my case, it took two. Gosh. I'll also say that the confidence i have that this approach will help find a path through even gnarly performance problems elegantly has gone way up. As said, i see it in clients reguarly, but there's nothing like personal and direct experience to reenforce a value proposition, eh?

Personal Practice So suggestion? If you're having hinky performance/pain issues, check in with a movement performance specialist. Here's a trainer listing. If you'd like a referal, call the office, and let them know mc suggested you ask them.Best with your practice,

mc

Related Posts

- Tendinopathy, tendinitis and Eccentric Exercise for rehab

- Ensuring that the *whole* muscle fires in a movement for real strength

- Why not move through pain

- dealing with chronic back pain

- active vs passive care/therapy

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Making the Ordinary Precious: revisiting the cup of coffee

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

The common practice/addictions often become common because they are accessible private or social pleasures around which we celebrate our days. What's problematic of course is when we're so wedded to such practices we can't seem to function without them. What's worse is when we find out that what we begin to call "functioning" isn't functioning - at least not optimally. Does that mean that these pleasures are evil? Can they be redeemed?

Recently, for example, i wrote about the effect of caffeine on our sleep quality. In sum, it can really really disrupt the restorative phase of sleep, the deep sleep cycle. Does that make coffee evil?

At the time i wrote the above post, i was actually *really* tired, heading into the last leg of a long business road trip. The airline had lost my bag, didn't know where it was and i was sitting in a workshop with a colleague saying to me "i've never seen you look so tired." Super.

Normally, at times like this i would have fled to the nearest coffee pot and tried to jack up. It then occurred to me that perhaps what my body was telling me was that i needed some sleep, and wouldn't it be nice, rather than interfering with the quality of that process, i actually let myself *get* some sleep that evening. So i opted not to get the coffee. And i didn't touch any coffee for the next four days. Alas i didn't have my zeo on this trip to check the shifts in deep sleep cycle, but i know how i felt with a four day java break. What happened on day four?

The Best Cup. When i was gigging my way through grad school, our band's drummer, Burt Harris, had a simple heuristic: no beer for the band till the last set break.

I was reminded of that on the last day of the workshop as a colleague, Jen Waak, and i went for lunch and decided to go for coffee at the neighboring starbucks where i had whatever passes for a small latte. i asked them please (a) to make it with love and (b) not to scald the milk, as this was a precious, rare coffee. It was fabulous. For which i was really grateful since not all starbucks experiences are equivalently dandy.

I was reminded of that on the last day of the workshop as a colleague, Jen Waak, and i went for lunch and decided to go for coffee at the neighboring starbucks where i had whatever passes for a small latte. i asked them please (a) to make it with love and (b) not to scald the milk, as this was a precious, rare coffee. It was fabulous. For which i was really grateful since not all starbucks experiences are equivalently dandy.

I know it had only been four days, but that coffee was *so* nice.

Considering how i'd felt getting my recovery back while not being on coffee, and how good that single latte tasted, well it got me thinking: maybe there are benefits to rare-ing out the common into the precious. That way perhaps even our simple pleasures can become exquisite ones - affordably, wonderfully, easily.

Fave Places for Precious Blends? Please let me know if you've given such a strategy a go and how it's working. Also, if you have a fave non-chain coffee place - what is it and why is it a fave. For me, when i'm in Edinburgh around the eScience Center, i make a pilgrimage to Black Medicine. Awesome

ps:

my gratitude to Heidi Rothenburg for the zipfizz on that first day off the plane with no luggage and no sleep.

Related posts

Recently, for example, i wrote about the effect of caffeine on our sleep quality. In sum, it can really really disrupt the restorative phase of sleep, the deep sleep cycle. Does that make coffee evil?

At the time i wrote the above post, i was actually *really* tired, heading into the last leg of a long business road trip. The airline had lost my bag, didn't know where it was and i was sitting in a workshop with a colleague saying to me "i've never seen you look so tired." Super.

Normally, at times like this i would have fled to the nearest coffee pot and tried to jack up. It then occurred to me that perhaps what my body was telling me was that i needed some sleep, and wouldn't it be nice, rather than interfering with the quality of that process, i actually let myself *get* some sleep that evening. So i opted not to get the coffee. And i didn't touch any coffee for the next four days. Alas i didn't have my zeo on this trip to check the shifts in deep sleep cycle, but i know how i felt with a four day java break. What happened on day four?

The Best Cup. When i was gigging my way through grad school, our band's drummer, Burt Harris, had a simple heuristic: no beer for the band till the last set break.

I know it had only been four days, but that coffee was *so* nice.

Considering how i'd felt getting my recovery back while not being on coffee, and how good that single latte tasted, well it got me thinking: maybe there are benefits to rare-ing out the common into the precious. That way perhaps even our simple pleasures can become exquisite ones - affordably, wonderfully, easily.

Fave Places for Precious Blends? Please let me know if you've given such a strategy a go and how it's working. Also, if you have a fave non-chain coffee place - what is it and why is it a fave. For me, when i'm in Edinburgh around the eScience Center, i make a pilgrimage to Black Medicine. Awesome

ps:

my gratitude to Heidi Rothenburg for the zipfizz on that first day off the plane with no luggage and no sleep.

Related posts

Tweet Follow @begin2dig

We're Walking Here - and feeling much better as a result: walking to rep in performance improvements

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Walking is an action most of us take for granted. It's such an automatic, effortless, thoughtless practice that we tend to forget it's actually a learned, practiced, skill. But it's this natural effortlessness of this deeply rep'ed & acquired practice that makes it so valuable for locking in better movement practice - what we practice when say working with a coach to tune dynamic joint movements (like those in z-health's R-Phase (overview) and I-Phase (overview) drills) into our lives.

Indeed, walking is a huge component of Z-Health (overview). Folks familiar with Z-Health assessments know that they usually begin and end a session with a walk – and often walk in between various drills done within a session. But folks are also encouraged to walk on their own immediately after their own practice to help dial in the work they do during their session. It’s this part of the role of the walk ithat is the focus of this article, but to get at that part, we need to understand a little bit more about why the walk is so valuable in general.

Indeed, walking is a huge component of Z-Health (overview). Folks familiar with Z-Health assessments know that they usually begin and end a session with a walk – and often walk in between various drills done within a session. But folks are also encouraged to walk on their own immediately after their own practice to help dial in the work they do during their session. It’s this part of the role of the walk ithat is the focus of this article, but to get at that part, we need to understand a little bit more about why the walk is so valuable in general.

Thoughtless Action – in a good way. Walking is a powerful communicator: it tells us a lot about our movement for a two key reasons we've touched on above: it’s autonomous, and its reflexive. Autonomous, from the greek auto, means can act on its own. So we can walk while we do other things. Like chew gum and talk all at the same time.

Walking, as noted, is not innate; it is rather like riding a bicycle: a learned skill. Indeed, research shows two interesting things (at least) about this skill acquisition: (1) that when we begin to acquire the skill has been pretty steady for us for hundreds of millions of years (Garwicz09) but (2) that this motor skill acquisition is also affected by cultural practices (Karasik10).

Once we do get going, we learn and practice this skill millions of times (each step is a practice) it becomes not only autonomous but reflexive. Reflexive means that the function moves from an act where we are thinking about it to something that is pre-cognitive – happens without having to think consciously about what to do. So with these two related qualities – autonomous and reflexive – we have an action that gives us a pretty good picture of how a person actually moves when they’re not thinking about it vs how a person may perform a less familiar action that requires their cognition and concentration. Something that is, in effect, thoughtless, therefore seems to give us a more accurate picture of the quality of a person’s movement

From this picture of the walk, Z-Health practitioners starting at an R-Phase certification level (the first cert, overviewed here) have a repertoire of drills available to help address the performance issue identified. Kinaesthetically, the person themselves also get feedback from the walk: it’s not unusual for the person walking to volunteer comments at the end of a session like “that feels more open” or “that’s looser” or “something’s easier.” In this respect, the walk forms a kind of assessment/reality check for the person to see how all those little z-drills have had not only a local but a more systemic effect on their performance.

From this picture of the walk, Z-Health practitioners starting at an R-Phase certification level (the first cert, overviewed here) have a repertoire of drills available to help address the performance issue identified. Kinaesthetically, the person themselves also get feedback from the walk: it’s not unusual for the person walking to volunteer comments at the end of a session like “that feels more open” or “that’s looser” or “something’s easier.” In this respect, the walk forms a kind of assessment/reality check for the person to see how all those little z-drills have had not only a local but a more systemic effect on their performance.

Loading Action More than just a self-check, because of its very systemic nature, walking is a great way to begin to enpattern (to coin a phrase) the better-ness being experienced in that self-check.

In other words, our walking at the end of a session begins to practice the new way we are moving as a result of the drills we practiced to move better. By checking to see if we are moving better, rather ironically, when we are moving better (shown in the better walk), we are helping to practice the better-ness. That’s why if we’re not moving better after a drill and a re-walk, we keep working out more drills until there is a betterness. And then we practice betterness – not by doing the drills that helped open up the paths – or not them alone – but by putting the positive effect of the drill into a real and fundamental movement. Thereby improving the movement (which is what we care about really more than an isolated gesture) into a positive feedback loop.

Making Music vs Playing Scales Walking post session or for that matter after doing our own mobility practice is rather like after doing scales on an instrument, playing the real piece; the real piece benefits not because the piece is playing scales, but because the scales give us skills that are useful in playing real pieces – any piece - better. But then, the magic is likewise that by playing the tune with these enhanced skills, the tune playing is itself also practice of the specific movement – as a whole. Feedback loop. Thus drills give us skills that improve movement such as the very familiar autonomous walking, and walking itself with this practice makes walking better. That post-session walk-in is a rather Magic Walk that captures and integrates into the Real Movement the experience built from the (corrective) drills.

But wait! There’s more. This practice of engraining drill practice, as it were, within the real movement – translating the skills of the scales to enhancing the quality of the performance – that work itself changes the shape of the movement.

That change in the walk is a physical thing: those physical changes are effectively structural. Consider if to improve the walk, the walk shows us that ankle work may help; we do ankle drills; re-walk. Better. That improved movement in the ankle is practiced within the walk itself. Improved movement means improved function; improved function, with many reps, leads quickly to fundamentally enhanced structure. Thus function creates structure.

This cycle of improving function to create improved structure occurs because we are plastic people. Woolf’s law demonstrates this effect with bone tissue (Frost01). Davis’s law shows this with our other tissues, like skin and fascia. And the SAID principle (specific adaptation to imposed demand) (Wallis & Logan) suggests this process of adaptation begins as soon as we introduce a demand upon the system.

But wait! There’s Even More.

Keeping it Real; Keeping it Cool Another aspect of the walk to dial in the drills we do for our performance improvement is that it may well also be neurologically soothing . The dynamic joint mobility drills in R-phase for instance help open up new signalling to the nervous system to say that a joint is moving better; a muscle is firing better and so we can move better.

To walk means to move. To move helps reduce stress (overview of why in 10 tips to de-stress); to move well means that a familiar, autonomous, reflexive act – something that therefore is in itself very low threat to the nervous system - is becoming better, easier, even less threatening – especially if there’s been any pain in the walk that’s lessened from our practice.. This better-ness amplifies all the positive benefits of movement. Easier, better, too, means less stress. We learn quickly from our body's responses that better movement means inner peace, happiness and perhaps improved prospects for a better incarnation: feeling better means easier to be nice rather than grumpy. And who wants to be grumpy and go to hell? Or reincarnate in a nasty place?

So we practice our drills, and then we walk them in. Beautiful music; beautiful movement.

PS - running and practicing running gait to reduce pain in running

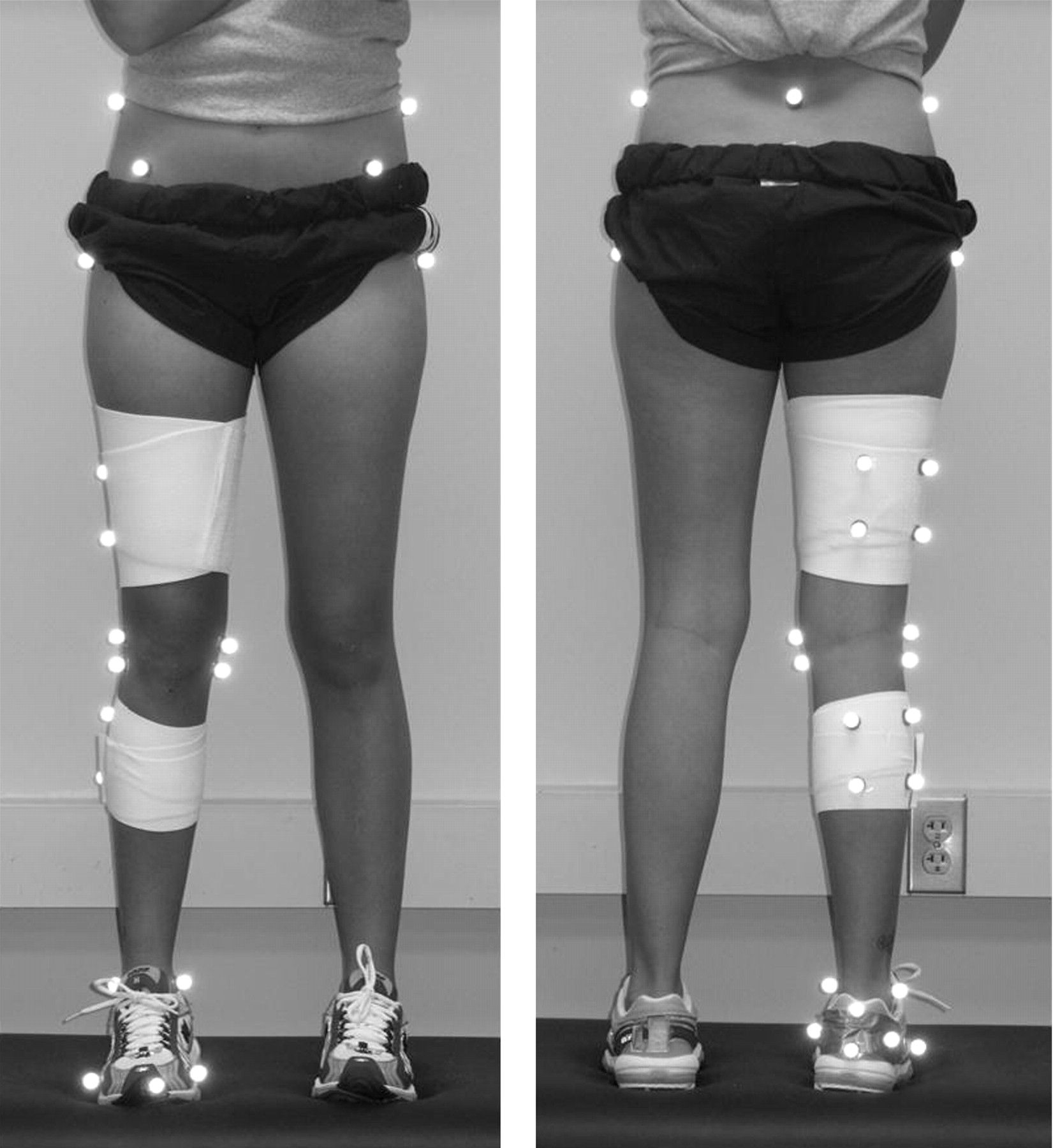

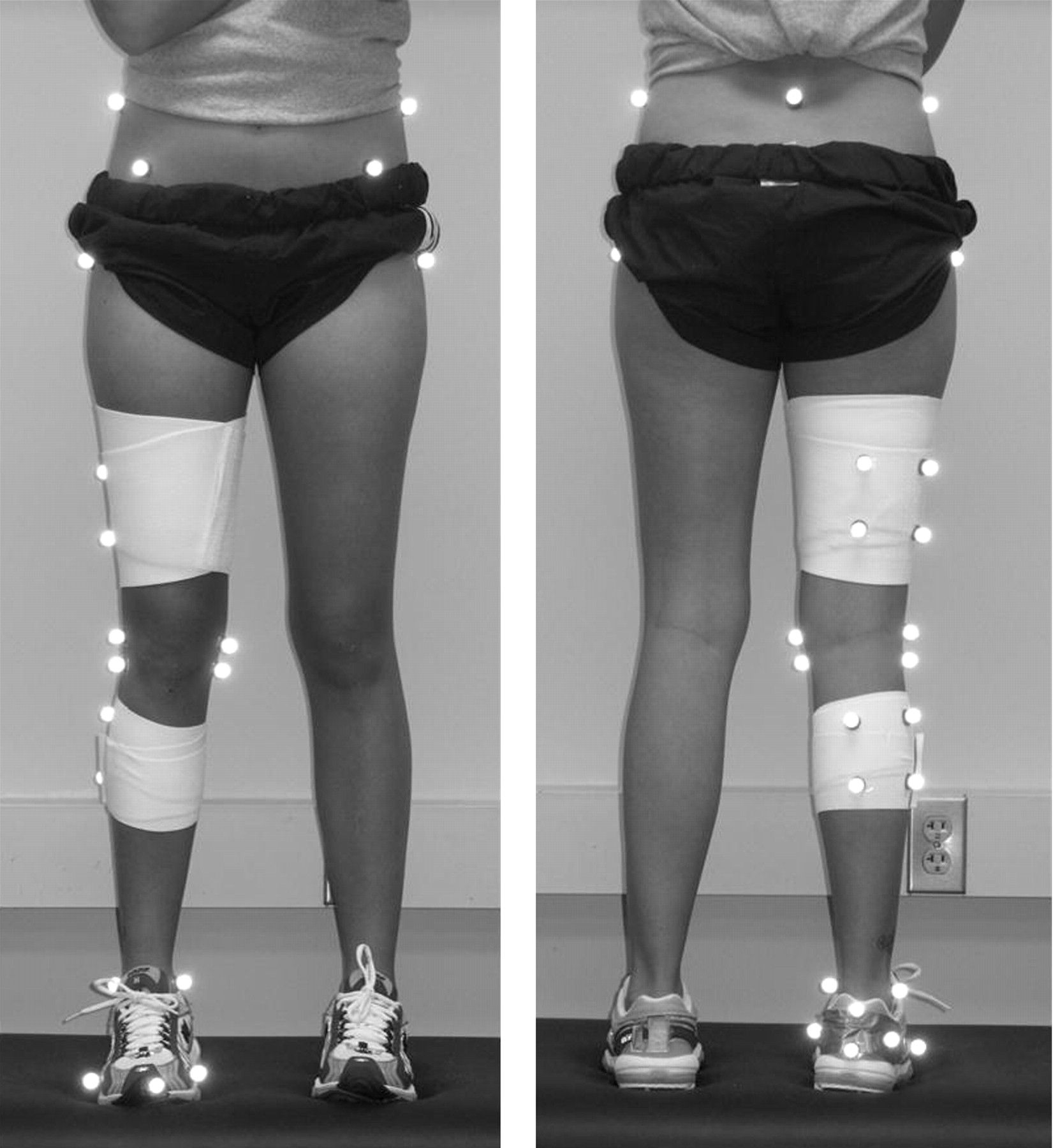

Recent research (Noehren10) considered that gosh, knee pain in runners (Patellofemoral pain syndrome) seems to be connected to hip mechanics. The approach to address this problem was to wire up study participants not unlike the way folks are wired up to map computer animation to human movement. In this case markers were placed on areas of the hip, low back, knee, shin and foot.

Recent research (Noehren10) considered that gosh, knee pain in runners (Patellofemoral pain syndrome) seems to be connected to hip mechanics. The approach to address this problem was to wire up study participants not unlike the way folks are wired up to map computer animation to human movement. In this case markers were placed on areas of the hip, low back, knee, shin and foot.

Runners were then asked to run on a treadmill and look at their movement performance data against a Normal Curve (shown below). Participants were asked over the course of 8 sessions of running on a treadmill to get their movement curve (the white line) to match the normal curve of treadmill running (the white line in the grey band). The amount of feedback given was tailed off over time to see how well the training was being internalized. Participants were also retested a month after the trial to see if the new patterns had stuck.

While the results were not statistically significant (but very close to being so), they showed that hip mechanics did change/improve, and that most importantly, knee pain went down. The paper is free and worth reading.

From a neurological/SAID principle lens, there are a couple of points here. First, if someone is having hip issues, is that all that's going on? sometimes hip issues are the result of low back stuff, upper back stuff and in particular foot/ankle stuff. Focusing on the hip alone may be part of why the results in improvement were not significant. One might argue, though, that in order for the person to "move their curve" as shown above, perhaps they were also working on the ankle and back position issues to achieve the hip effect.

Second, running on a treadmill is a kind of weird thing relative to normal running or walking gait. When we run we choose our pace and stride length - it varries. On a treadmill, there's not much room for those subtle variations; the vestibular/visual dissonance also seems to create a performance hit vs land running/walking (ever feel a bit dizzy coming off a treadmill?)

Third of course, these folks all seem to be running with squishy largely not bendy heal-striking shoes. How about just thinking about getting out of those shoes or perhaps learning to get up into more natural/barefoot running type gait??

So what i wonder to myself is that if some of these folks with knee pain had come to see a Z-Health person with even just an R-Phase cert under their belts, and they'd been asked by said Zed folks to go for a walk (rather than step on a treadmill) to look at how they move at their own pace, in their own way, what might have been seen? Would a few reps with a few simple but very precicise R-Phase drills, followed by the Magic Post Session Walk have helped set up this better function sooner, faster, easier, and potentially have even greater benefit since the practice is located in the every day of the walk (using the SAID principle of specific adaptation) rather than the artifice of the treadmill? Just a question, but i'm guessing based on practice the answer is "uh huh."

And the beat goes on.

A few Refs

Walking is an action most of us take for granted. It's such an automatic, effortless, thoughtless practice that we tend to forget it's actually a learned, practiced, skill. But it's this natural effortlessness of this deeply rep'ed & acquired practice that makes it so valuable for locking in better movement practice - what we practice when say working with a coach to tune dynamic joint movements (like those in z-health's R-Phase (overview) and I-Phase (overview) drills) into our lives.

Thoughtless Action – in a good way. Walking is a powerful communicator: it tells us a lot about our movement for a two key reasons we've touched on above: it’s autonomous, and its reflexive. Autonomous, from the greek auto, means can act on its own. So we can walk while we do other things. Like chew gum and talk all at the same time.

Walking, as noted, is not innate; it is rather like riding a bicycle: a learned skill. Indeed, research shows two interesting things (at least) about this skill acquisition: (1) that when we begin to acquire the skill has been pretty steady for us for hundreds of millions of years (Garwicz09) but (2) that this motor skill acquisition is also affected by cultural practices (Karasik10).

Once we do get going, we learn and practice this skill millions of times (each step is a practice) it becomes not only autonomous but reflexive. Reflexive means that the function moves from an act where we are thinking about it to something that is pre-cognitive – happens without having to think consciously about what to do. So with these two related qualities – autonomous and reflexive – we have an action that gives us a pretty good picture of how a person actually moves when they’re not thinking about it vs how a person may perform a less familiar action that requires their cognition and concentration. Something that is, in effect, thoughtless, therefore seems to give us a more accurate picture of the quality of a person’s movement

From this picture of the walk, Z-Health practitioners starting at an R-Phase certification level (the first cert, overviewed here) have a repertoire of drills available to help address the performance issue identified. Kinaesthetically, the person themselves also get feedback from the walk: it’s not unusual for the person walking to volunteer comments at the end of a session like “that feels more open” or “that’s looser” or “something’s easier.” In this respect, the walk forms a kind of assessment/reality check for the person to see how all those little z-drills have had not only a local but a more systemic effect on their performance.

From this picture of the walk, Z-Health practitioners starting at an R-Phase certification level (the first cert, overviewed here) have a repertoire of drills available to help address the performance issue identified. Kinaesthetically, the person themselves also get feedback from the walk: it’s not unusual for the person walking to volunteer comments at the end of a session like “that feels more open” or “that’s looser” or “something’s easier.” In this respect, the walk forms a kind of assessment/reality check for the person to see how all those little z-drills have had not only a local but a more systemic effect on their performance.Loading Action More than just a self-check, because of its very systemic nature, walking is a great way to begin to enpattern (to coin a phrase) the better-ness being experienced in that self-check.

In other words, our walking at the end of a session begins to practice the new way we are moving as a result of the drills we practiced to move better. By checking to see if we are moving better, rather ironically, when we are moving better (shown in the better walk), we are helping to practice the better-ness. That’s why if we’re not moving better after a drill and a re-walk, we keep working out more drills until there is a betterness. And then we practice betterness – not by doing the drills that helped open up the paths – or not them alone – but by putting the positive effect of the drill into a real and fundamental movement. Thereby improving the movement (which is what we care about really more than an isolated gesture) into a positive feedback loop.

Making Music vs Playing Scales Walking post session or for that matter after doing our own mobility practice is rather like after doing scales on an instrument, playing the real piece; the real piece benefits not because the piece is playing scales, but because the scales give us skills that are useful in playing real pieces – any piece - better. But then, the magic is likewise that by playing the tune with these enhanced skills, the tune playing is itself also practice of the specific movement – as a whole. Feedback loop. Thus drills give us skills that improve movement such as the very familiar autonomous walking, and walking itself with this practice makes walking better. That post-session walk-in is a rather Magic Walk that captures and integrates into the Real Movement the experience built from the (corrective) drills.

But wait! There’s more. This practice of engraining drill practice, as it were, within the real movement – translating the skills of the scales to enhancing the quality of the performance – that work itself changes the shape of the movement.

That change in the walk is a physical thing: those physical changes are effectively structural. Consider if to improve the walk, the walk shows us that ankle work may help; we do ankle drills; re-walk. Better. That improved movement in the ankle is practiced within the walk itself. Improved movement means improved function; improved function, with many reps, leads quickly to fundamentally enhanced structure. Thus function creates structure.

This cycle of improving function to create improved structure occurs because we are plastic people. Woolf’s law demonstrates this effect with bone tissue (Frost01). Davis’s law shows this with our other tissues, like skin and fascia. And the SAID principle (specific adaptation to imposed demand) (Wallis & Logan) suggests this process of adaptation begins as soon as we introduce a demand upon the system.

But wait! There’s Even More.

Keeping it Real; Keeping it Cool Another aspect of the walk to dial in the drills we do for our performance improvement is that it may well also be neurologically soothing . The dynamic joint mobility drills in R-phase for instance help open up new signalling to the nervous system to say that a joint is moving better; a muscle is firing better and so we can move better.

To walk means to move. To move helps reduce stress (overview of why in 10 tips to de-stress); to move well means that a familiar, autonomous, reflexive act – something that therefore is in itself very low threat to the nervous system - is becoming better, easier, even less threatening – especially if there’s been any pain in the walk that’s lessened from our practice.. This better-ness amplifies all the positive benefits of movement. Easier, better, too, means less stress. We learn quickly from our body's responses that better movement means inner peace, happiness and perhaps improved prospects for a better incarnation: feeling better means easier to be nice rather than grumpy. And who wants to be grumpy and go to hell? Or reincarnate in a nasty place?

So we practice our drills, and then we walk them in. Beautiful music; beautiful movement.

PS - running and practicing running gait to reduce pain in running

Recent research (Noehren10) considered that gosh, knee pain in runners (Patellofemoral pain syndrome) seems to be connected to hip mechanics. The approach to address this problem was to wire up study participants not unlike the way folks are wired up to map computer animation to human movement. In this case markers were placed on areas of the hip, low back, knee, shin and foot.

Recent research (Noehren10) considered that gosh, knee pain in runners (Patellofemoral pain syndrome) seems to be connected to hip mechanics. The approach to address this problem was to wire up study participants not unlike the way folks are wired up to map computer animation to human movement. In this case markers were placed on areas of the hip, low back, knee, shin and foot.Runners were then asked to run on a treadmill and look at their movement performance data against a Normal Curve (shown below). Participants were asked over the course of 8 sessions of running on a treadmill to get their movement curve (the white line) to match the normal curve of treadmill running (the white line in the grey band). The amount of feedback given was tailed off over time to see how well the training was being internalized. Participants were also retested a month after the trial to see if the new patterns had stuck.

While the results were not statistically significant (but very close to being so), they showed that hip mechanics did change/improve, and that most importantly, knee pain went down. The paper is free and worth reading.

From a neurological/SAID principle lens, there are a couple of points here. First, if someone is having hip issues, is that all that's going on? sometimes hip issues are the result of low back stuff, upper back stuff and in particular foot/ankle stuff. Focusing on the hip alone may be part of why the results in improvement were not significant. One might argue, though, that in order for the person to "move their curve" as shown above, perhaps they were also working on the ankle and back position issues to achieve the hip effect.

Second, running on a treadmill is a kind of weird thing relative to normal running or walking gait. When we run we choose our pace and stride length - it varries. On a treadmill, there's not much room for those subtle variations; the vestibular/visual dissonance also seems to create a performance hit vs land running/walking (ever feel a bit dizzy coming off a treadmill?)

Third of course, these folks all seem to be running with squishy largely not bendy heal-striking shoes. How about just thinking about getting out of those shoes or perhaps learning to get up into more natural/barefoot running type gait??

So what i wonder to myself is that if some of these folks with knee pain had come to see a Z-Health person with even just an R-Phase cert under their belts, and they'd been asked by said Zed folks to go for a walk (rather than step on a treadmill) to look at how they move at their own pace, in their own way, what might have been seen? Would a few reps with a few simple but very precicise R-Phase drills, followed by the Magic Post Session Walk have helped set up this better function sooner, faster, easier, and potentially have even greater benefit since the practice is located in the every day of the walk (using the SAID principle of specific adaptation) rather than the artifice of the treadmill? Just a question, but i'm guessing based on practice the answer is "uh huh."

And the beat goes on.

pps - if you're interested in the R-Phase cert, or in checking out zed (via the essentials of elite performance dvd or course) here's more info about z-health and the approaches here; if you do decide to take a cert, please consider indicating you came in via mc (that's me). We don't get paid money for any referals, but we do get some money off our own continuing ed with zed. Which is cool. And appreciated.

A few Refs

Frost HM (2001). From Wolff's law to the Utah paradigm: insights about bone physiology and its clinical applications. The Anatomical record, 262 (4), 398-419 PMID: 11275971

Garwicz, M., Christensson, M., & Psouni, E. (2009). A unifying model for timing of walking onset in humans and other mammals Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106 (51), 21889-21893 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0905777106

Karasik LB, Adolph KE, Tamis-Lemonda CS, & Bornstein MH (2010). WEIRD walking: cross-cultural research on motor development. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 33 (2-3), 95-6 PMID: 20546664

Noehren, B., Scholz, J., & Davis, I. (2010). The effect of real-time gait retraining on hip kinematics, pain and function in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome British Journal of Sports Medicine DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069112

Wallis, Earl L and Logan, Gene Adams, 1964 Figure improvement and body conditioning through exercise, Prentice Hall, NY. [presentation of SAID principle]Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Friday, October 15, 2010

Squish your Eyes - and Relax

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

A while ago over at iamgeekfit, i posted ten tips to destress - very much related to hormone responses and ph balance. Well, recently learned there's one more thing we can do to relax that's pretty durn neural: squish our eyes. With little circles.

How do it? As eric cobb puts it, imagine you're picking up a grape (using all your fingers). Take that position to the eye and press/massage for about 30seconds.

Yes, closing eyes and massaging around the eye, pushing gently on the eyeball through the lid, will help calm us down based on something called the "oculocadiac reflex"

In other words, the eyes, via a big nerve group in the head/face (the trigeminal nerve) are connected to this great big vagus nerve; the vagus nerve goes through touching our heart, our lungs and importantly our guts.

Doing a little eye squishing massage will help trigger the calming wonder that is the provinence of the valgus nerve.

Doing a little eye squishing massage will help trigger the calming wonder that is the provinence of the valgus nerve.

If you dig these kind of tips there's way more eyeball wonderfulness covered in the Complete Athlete Vol 1 DVD. Turns out our eyes are important for more than vision.

Doing eye squishing daily - may make more of a difference than just feeling relaxed. If you give it a go for two weeks, daily, please let me know what you notice changes in your well being/performance.

Related

How do it? As eric cobb puts it, imagine you're picking up a grape (using all your fingers). Take that position to the eye and press/massage for about 30seconds.

Yes, closing eyes and massaging around the eye, pushing gently on the eyeball through the lid, will help calm us down based on something called the "oculocadiac reflex"

In other words, the eyes, via a big nerve group in the head/face (the trigeminal nerve) are connected to this great big vagus nerve; the vagus nerve goes through touching our heart, our lungs and importantly our guts.

Doing a little eye squishing massage will help trigger the calming wonder that is the provinence of the valgus nerve.

Doing a little eye squishing massage will help trigger the calming wonder that is the provinence of the valgus nerve.If you dig these kind of tips there's way more eyeball wonderfulness covered in the Complete Athlete Vol 1 DVD. Turns out our eyes are important for more than vision.

Doing eye squishing daily - may make more of a difference than just feeling relaxed. If you give it a go for two weeks, daily, please let me know what you notice changes in your well being/performance.

Related

- practicing on the other side of the weigth room: tuning visual vestibular and proprioceptive systems

- overview: the complete athlete, vol 1

Labels:

eyes,

massage.,

relaxation

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Caffeine makes us Crazy - or at least messes with our sleep

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

i *love* good coffee. You? Do you know how you react to coffee? Do you find caffeine keeps you awake/alert? Yes? or maybe you find it doesn't affect your getting to sleep? We know that the magic in coffee is caffeine. Guess what? apparently whether or not we can fall asleep with caffeine is less of an issue than what it does to our sleep quality, in particular, our deep sleep state. That is, it screws it up.

i *love* good coffee. You? Do you know how you react to coffee? Do you find caffeine keeps you awake/alert? Yes? or maybe you find it doesn't affect your getting to sleep? We know that the magic in coffee is caffeine. Guess what? apparently whether or not we can fall asleep with caffeine is less of an issue than what it does to our sleep quality, in particular, our deep sleep state. That is, it screws it up.

So yes, we might be able to get to sleep (or not) with caffeine in our systems (caffeine genetics is cool), but once we are asleep - based on what's happening in our brain - we just mayn't have enough signaling in the presence of caffeine to tell us to get to DEEP sleep. Wild, eh?

So what's caffeine doing to us? There's a great detailed write up of the chemistry of caffeine and the brain (calmly titled "Is caffeine a health hazard?") by Ben Best. If i can summarise that article without wrecking it, here's the simplified version, and it's so cool, it just makes sense.

Energy. All or our systems require ATP to do work. Adenosine Triphosphate. Folks into performance are v. familiar with ATP in terms of energy system work, and how Fat for instance is our biggest but slowest generating source of ATP. ATP produces energy by being broken apart into two parts: adenosine and adenosinediphosphate. The work of energy production is a cycle of putting a and adp together again to from new ATP.

Fatigue. Fatigue is a really interesting process. All we're going to look at here is one tiny tiny bit. When we get fatigued and need rest, the adenosine that gets generated from ATP being broken down, rather than being reassembled into new ATP actually just builds up around the cells and doesn't get used. That's a really good thing. Adenosine on it's one is a brain signaller. As adenosine builds up in this fluid around the cells a bunch of things happen, including effectively signaling the brain to shift down, and when asleep to fasciliate deep, slow wave sleep. As the presence of adenosine goes up, brain wave activity goes down, deep sleep can happen.

Caffeine the Disruptor. An amazing property of caffiene is that it is a Master of Disguise. It connects with adenosine receptors (getting across the blood brain barrier) so that adenosine can't get to those receptors (A1 in particular), and effectively means that the brain doesn't perceive the degree of adenosine build up, and so the signaling to slow the heck down can't happen. All sorts of tests show that with caffeine folks do better in various kinds of tasks, and has been tested with soldiers and athletes rather a lot. But even more recently with soldiers, there's an effort to get away from "stimulants" and think more about scheduling.

Bottom line is that caffeine a way to fake out our system into believing its less tired than it is. There are costs. It's pretty easy to see that while coffee'ing up will give most of us a jolt, we're still actually fatigued, and we are artificially asking our bodies to work beyond what they require for optimal function.

The effects are at least in two ways:

The other thing is that caffeine can actually take awhile to flush from our systems. Yesterday in talking about the value of darkness at night for sleep quality, i mentioned zeo as a tool to see how one's sleep quality changes. We use zeo in our lab for "self-monitoring." We can see that deep sleep quality seems to stay effected for days after even with single doses of caffeine. Bummer.

As zeo sleep researcher Stephan Fabregas has said previously at b2d, using caffeine in extremis for the occaision we need it, it can be great and useful. As a regular practice, maybe not so good. Bummer again. But that turns out to be the same for athletes using caffeine to help perk performance too.

The worst part of caffeine apparently is coming off it. Get through that, and sleep gets better, and we need caffeine less. How about that?

Break the cycle (of dependence); improve sleep quality, improve recovery and quality of life.

If you are a big starbucks mega coffee drinker, and you try going from Really Big to Not Quite So Big to maybe one less a day, let me know if you notice a difference over time of being on less or none of the stuff.

Good luck on your caffeine control mission.

Quick Ref

So yes, we might be able to get to sleep (or not) with caffeine in our systems (caffeine genetics is cool), but once we are asleep - based on what's happening in our brain - we just mayn't have enough signaling in the presence of caffeine to tell us to get to DEEP sleep. Wild, eh?

So what's caffeine doing to us? There's a great detailed write up of the chemistry of caffeine and the brain (calmly titled "Is caffeine a health hazard?") by Ben Best. If i can summarise that article without wrecking it, here's the simplified version, and it's so cool, it just makes sense.

Energy. All or our systems require ATP to do work. Adenosine Triphosphate. Folks into performance are v. familiar with ATP in terms of energy system work, and how Fat for instance is our biggest but slowest generating source of ATP. ATP produces energy by being broken apart into two parts: adenosine and adenosinediphosphate. The work of energy production is a cycle of putting a and adp together again to from new ATP.

Fatigue. Fatigue is a really interesting process. All we're going to look at here is one tiny tiny bit. When we get fatigued and need rest, the adenosine that gets generated from ATP being broken down, rather than being reassembled into new ATP actually just builds up around the cells and doesn't get used. That's a really good thing. Adenosine on it's one is a brain signaller. As adenosine builds up in this fluid around the cells a bunch of things happen, including effectively signaling the brain to shift down, and when asleep to fasciliate deep, slow wave sleep. As the presence of adenosine goes up, brain wave activity goes down, deep sleep can happen.

Caffeine the Disruptor. An amazing property of caffiene is that it is a Master of Disguise. It connects with adenosine receptors (getting across the blood brain barrier) so that adenosine can't get to those receptors (A1 in particular), and effectively means that the brain doesn't perceive the degree of adenosine build up, and so the signaling to slow the heck down can't happen. All sorts of tests show that with caffeine folks do better in various kinds of tasks, and has been tested with soldiers and athletes rather a lot. But even more recently with soldiers, there's an effort to get away from "stimulants" and think more about scheduling.

Bottom line is that caffeine a way to fake out our system into believing its less tired than it is. There are costs. It's pretty easy to see that while coffee'ing up will give most of us a jolt, we're still actually fatigued, and we are artificially asking our bodies to work beyond what they require for optimal function.

The effects are at least in two ways:

- compromised deep sleep quality means our recovery is compromised, and if as athletes we're trying to build physical function, deep sleep is where that building takes place, so we've just screwed the efficacy of our build phase;

- because we're actually still fatigued, and not getting sleep, sleep deprivation effects kick in. Stress goes up, fucntion goes down, ability even to process food, have sex, do anything gets screwed up. Irony eh? we take caffeine to perk up and it ends up actually screwing up our sleep recovery.

As zeo sleep researcher Stephan Fabregas has said previously at b2d, using caffeine in extremis for the occaision we need it, it can be great and useful. As a regular practice, maybe not so good. Bummer again. But that turns out to be the same for athletes using caffeine to help perk performance too.

The worst part of caffeine apparently is coming off it. Get through that, and sleep gets better, and we need caffeine less. How about that?

Break the cycle (of dependence); improve sleep quality, improve recovery and quality of life.

If you are a big starbucks mega coffee drinker, and you try going from Really Big to Not Quite So Big to maybe one less a day, let me know if you notice a difference over time of being on less or none of the stuff.

Good luck on your caffeine control mission.

Quick Ref

Gore RK, Webb TS, & Hermes ED (2010). Fatigue and stimulant use in military fighter aircrew during combat operations. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine, 81 (8), 719-27 PMID: 20681231Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Ferré S (2010). Role of the central ascending neurotransmitter systems in the psychostimulant effects of caffeine. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 20 Suppl 1 PMID: 20182056

Yang, A., Palmer, A., & Wit, H. (2010). Genetics of caffeine consumption and responses to caffeine Psychopharmacology, 211 (3), 245-257 DOI: 10.1007/s00213-010-1900-1

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

COACHING with dr. m.c.

COACHING with dr. m.c.