Sunday, May 16, 2010

Coming Up at b2d: satiety, embodied brains and movement makes us smarter?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Hello Kind b2d Readers,

Been on the road for two weeks of non-stop work, so it's been a bit of a challenge to get content to the screen. And now i have a wee cold (keeping the grosser symptoms at bay with some chelated zinc), so as you know, that can kinda slow down the cognitive processes, too.

Coming Up at b2d: Just wanted to let you know, therefore, about some of the articles on the blocks for the near future:

Thanks for hanging in with b2d,

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Been on the road for two weeks of non-stop work, so it's been a bit of a challenge to get content to the screen. And now i have a wee cold (keeping the grosser symptoms at bay with some chelated zinc), so as you know, that can kinda slow down the cognitive processes, too.

Coming Up at b2d: Just wanted to let you know, therefore, about some of the articles on the blocks for the near future:

- hunger as habit, and how that relates to what science seems to know about the markers around hunger like satiation and satiety; the role of energy density.

satiation is a big area of study - if we have great homeostatic mechanisms as an organism, why does weight get out of control? What are tested strategies to help get our eating back under control - to get the homeostatic to kick in to support hedonic change?

- the SAID principle - where'd it come from and what does it mean for training?

- And Related:

Is transferecnce (doing one activity in one domain that *seems* to contribute to another activity) a poor analogy for what's happening in sports training?

And in my increasingly fave area of the Embodied Brain (we're not just brains with bods attached)

- Exercise: competitive advantage

There seems to be an increasing amount of work that shows that exercise has a strong relationship to smarts. So, if our work requires us to be innovative, smart etc, not only staying healthy but fit - maybe it's mitochondrial processing that's pumping all that fresh o2 through the system - seems to mean a lot for a cognitive edge.

- Movement for Mental Function - related

there's some wild studies that show that when kids are let to gesture when doing long division, they do better at it then when they have to keep their hands still, they do less well. Our bodies help our brains do cognitive things. So why - i say SO WHY - are our office worker environments designed to be seated and still?

Thanks for hanging in with b2d,

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Friday, May 7, 2010

Muscle Cramps in Calves when Running in Vibram FiveFingers: what is it, what causes it and what can be done about it?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

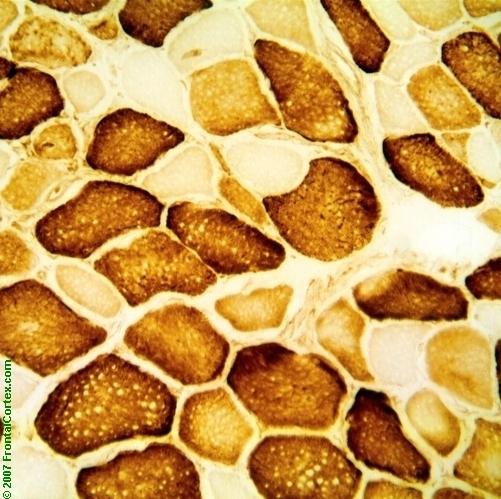

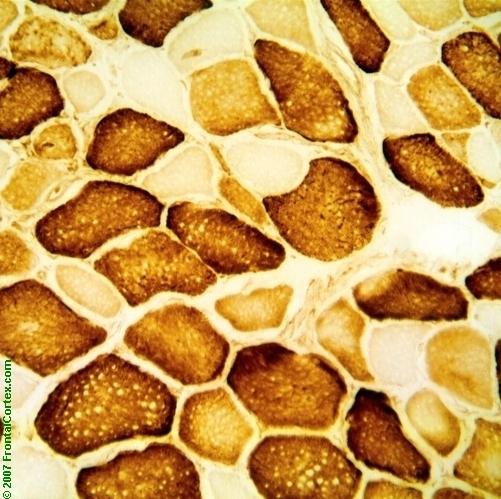

Runners Cramp - Calves cramping - it's AWFUL. In talking with folks who run in VFF's it seems that one usual side effect initially at least is that, when picking up the pace in VFF's (perhaps especially up hill), calves may start to cramp up. Guaranteed, if we keep going with this run, once that cramp starts, the calf or calves will turn to unyielding, painful rock. What can be surprising is how quickly into a run this seize up can happen. What the heck is going on, and what might help stop it from happening.

Runners Cramp - Calves cramping - it's AWFUL. In talking with folks who run in VFF's it seems that one usual side effect initially at least is that, when picking up the pace in VFF's (perhaps especially up hill), calves may start to cramp up. Guaranteed, if we keep going with this run, once that cramp starts, the calf or calves will turn to unyielding, painful rock. What can be surprising is how quickly into a run this seize up can happen. What the heck is going on, and what might help stop it from happening.

There could be lots going on, so i'm not trying to be comprehensive and exhaustive - not sure that's possible. The goal of this post is to look at pain generally, muscle cramps in particular and what's hypothesised about causes, introduce a newer model not seen in web discussions of cramp, and propose a refinement for that model. Finally, some practical suggestions of getting out of that cramp while heading to barefoot running freedom.

Pain is a signal for Change

Based on work in pain, and as summarized in work by David Butler like the plain language Explain

Based on work in pain, and as summarized in work by David Butler like the plain language Explain  Pain

Pain , pain is a signal for change; pain does not necessarily, however, equal injury, and the site of pain is not always the source of pain; treating the site of pain therefore can be a losing proposition.

, pain is a signal for change; pain does not necessarily, however, equal injury, and the site of pain is not always the source of pain; treating the site of pain therefore can be a losing proposition.

I've used the analogy of a car oil gauge regularly reading low. One solution is to top up the oil in the engine so that the gauge reads the right level. That level will only last short term and needs to be repeated regularly - and in the interim, what related problems might be developing from such regular loses?

Another solution is to do a diagnostic to find out what else might be going on - like a leak in the engine block where actually a bolt may simply need to be tightened (or an entire gasket in the block replaced - can you tell i'm having flashbacks of stripping the head of an engine in the middle of the bush on an old carola. never mind; i digress). The point is, getting away from site = source often leads to better results.

In the car analogy, finding a more fundamental issue, performing a wee tweak and testing if that tweak will work means that the oil level stays where it's supposed to be for as long as it's supposed to be there. Both approaches are a kind of solution; the benefits on the system and the wallet are better in the latter case.

What's a Cramp in the Calves Anyway?

So taking the above pain thesis into account, what does this mean for the calves rock effect?

What's a Cramp? A cramp is an involuntary and intense contraction of a muscle. What causes a cramp is a subject of much discussion, and poorly understood. A quick check on the web doesn't get at too much about why this contraction occurs.

WHy a cramp? The usual checks: electrolytes, hydration, low carbs, tight muscles to begin with are offered up not as reasons, but of things somehow thought to be related to cramping. Here's an examplary summary of that kind. In this model, the thesis seems to go, the muscles don't have the chemical materials needed to fire in that working limb properly so they effectively rigor mortis up. This rationale for cramp has been more or less tossed out as demonstrated here in 04, and as summarised in this recent BMJ review article. First, on dehydration:

Here's another view of cramps by Luke Hoffman that could be written for VFF runners:

The above describes what might be called "voluntary contraction" - not quite the same as involuntary. If we take the above council about voluntary cramps to bear, however, what should be the case is once a cramp starts, we should stretch it out, and wait for the fatigue to pass from that contraction, and recover, and really stop doing what we were doing - running on the forefoot. Consequently, Pose & VFF runners who run on the forefoot should be cramping all the time. And if we believe work in barefoot running, this is rather how we're designed to run. So, hmm, maybe not.

None of these explanations therefore is complete it seems, to explain cramping we see in the calves that comes on unexpectedly, as lots of well fed, well hydrtated, well electolyted people who stretch still get cramps, and these weird cramps in VFF's in particular.

So why does this cramp only happen *some* of the time - especially if all the typical niceities of cramp avoidance are observed? For me, for instance, it happened first when i started practicing actually bringing the heel of the foot down more (extending the calf) when running, rather than staying up on the forefoot. So, maybe it's not (entirely) about the calves?

Altered Neuromuscular Control. In the research one of the explanations around cramp is: maybe the muscle is just not strong enough to do what is being asked of it, for the duration it's being asked to operate at this level - hence fatiguing - and it's that fatigue that is setting up EAMC: exercise-associated muscle cramping. This hypothesis, also known as "altered neuromuscular control" was first proposed in 1996, so that's how new this stuff is. A key part of this model is that the neuromuscular control issue is located in the SPINE, not at the site of the issue - the site is paying for what's going on at the source.

So in the Pain as Signal to Change perspective, cramps are painful; they are a signal to change. The altered neuromuscular control model suggests, stretch it out and recover. Related work suggests, improve strength/stamina to reduce fatigue and reduce this muscle cramp response. Both have in common that fatigue is causing neural level loss of appropriate control.

So in the Pain as Signal to Change perspective, cramps are painful; they are a signal to change. The altered neuromuscular control model suggests, stretch it out and recover. Related work suggests, improve strength/stamina to reduce fatigue and reduce this muscle cramp response. Both have in common that fatigue is causing neural level loss of appropriate control.

Wildly Hypothesising? What's going on when this particular response occurs well before one would think a muscle used to running for miles and miles starts to go all crampy?

In work pionered by LeDoux in the nineties

work pionered by LeDoux in the nineties , he showed that the brain processes emotional responses like fear/threat without the conscious brain being involved. It happens fast, at a low level, without cognitive involvement and has immediate chemical consequences in the system (nice review of this and related work here by Ohman, 2005). In other words, perhaps there's some other *thing* happening in the sensory-motor exerperience that is saying "not good" and the result is this fatigue-like chemical messaging system that sets off early light cramp signals - that if ignored will just get louder until one is forced to change patterns.

, he showed that the brain processes emotional responses like fear/threat without the conscious brain being involved. It happens fast, at a low level, without cognitive involvement and has immediate chemical consequences in the system (nice review of this and related work here by Ohman, 2005). In other words, perhaps there's some other *thing* happening in the sensory-motor exerperience that is saying "not good" and the result is this fatigue-like chemical messaging system that sets off early light cramp signals - that if ignored will just get louder until one is forced to change patterns.

In Z-Health, Eric Cobb translates this fear response into the nervous system's job to perceive threat or no threat: if there's a perception of threat, the system starts to shut down (example in arthrokinetic reflex). What might be the threat ocuring in VFF ocaisional calve cramping? The system may be literally putting on the breaks to what it perceives as a threatening to it's well being practice.

It's easy to see that if the nervous system perceives that the task - going at a particular speed in a particular way - is causing part of the system to be over-taxed, it's going to respond to that as a threat or non-optimal situation, and if it takes pain to get change, well, whatever it takes.

Personal Experience. Taking a Z-Health approach to this experience, i think i've learned to become more alert to any pain signal my bod sends up in an athletic effort. So in this case, if and when these cramps begin, they usually start with a very mild "uh oh" twinge of "about to turn to rock if you don't respond."

There are two simple things that z-health suggests for rehabbing a movement with the cue of "never move into pain:"

Guided by the Nose: run to pace inhalation. Another technique i've been using and coaching to help head off cramps and adapt to barefooting generally is to explore gaiting running speed with ability to stay breathing in through one's nose. If running at a clip where i have to mouth breath, i slow it down (i find if i hit that level, it's pretty hard to get it back to nose inhaling). This approach is just one way at least some of the time to practice running reps quality rather than overdriving the other parts of the system.

Deeper Tune Up: Starting from the Source

So we've seen one theory in the research is around muscular fatigue inducing EAMC; getting stronger in those areas where muscles cramped seemed to help. In one study. That's great. Another possibility - that can lead to faster fatigue - is if there's some kind of issue in one's movement that is causing perhaps other muscles to compensate for other weaknesses, and causing fatigue/pain/signaling in the calves faster that should happen for that group. So while a solution may be to do extra strength work, maybe a faster solution may actually be to look at one's movement as a whole.

In other words, the calves may be plenty strong IF everything else is firing up appropriately, but they may be being asked to super compenate for other stuff, that if those other movement issues were addressed, wouldn't cause the problem.

There's value therefore in (a) having a movement assessment and (b) practicing dynamic joint mobility and sensory-motor work to ensure great movement, and ability to maintain great, clean movement.

Summary: Avoiding Running Cramps in VFF's

Based on the latest research, EAMC cramps are about temporary loss of clear neuromuscular control. The best model so far to explain this effect is fatigue. A known way to work out a cramp is to lengthen the muscle. There may however be other approaches that just haven't been researched that also seem to work. The hypothesis here is that these approaches are dealing with neurological signaling, too, taking advantage of the sensory-motor system.

Some pragmatic responses therefore if cramp occurs are:

During a Run: Assuming one is not dehydrated, de-electrolyted, or have squirrels biting their calves while running,

And before That

Consider a movement assessment to check for what Gray Cook calls "weak links" so as not to build strength on top of dysfunction.

Let me know what works for you.

Citations

Tweet Follow @begin2dig

There could be lots going on, so i'm not trying to be comprehensive and exhaustive - not sure that's possible. The goal of this post is to look at pain generally, muscle cramps in particular and what's hypothesised about causes, introduce a newer model not seen in web discussions of cramp, and propose a refinement for that model. Finally, some practical suggestions of getting out of that cramp while heading to barefoot running freedom.

Pain is a signal for Change

Based on work in pain, and as summarized in work by David Butler like the plain language Explain

Based on work in pain, and as summarized in work by David Butler like the plain language Explain I've used the analogy of a car oil gauge regularly reading low. One solution is to top up the oil in the engine so that the gauge reads the right level. That level will only last short term and needs to be repeated regularly - and in the interim, what related problems might be developing from such regular loses?

Another solution is to do a diagnostic to find out what else might be going on - like a leak in the engine block where actually a bolt may simply need to be tightened (or an entire gasket in the block replaced - can you tell i'm having flashbacks of stripping the head of an engine in the middle of the bush on an old carola. never mind; i digress). The point is, getting away from site = source often leads to better results.

In the car analogy, finding a more fundamental issue, performing a wee tweak and testing if that tweak will work means that the oil level stays where it's supposed to be for as long as it's supposed to be there. Both approaches are a kind of solution; the benefits on the system and the wallet are better in the latter case.

What's a Cramp in the Calves Anyway?

So taking the above pain thesis into account, what does this mean for the calves rock effect?

What's a Cramp? A cramp is an involuntary and intense contraction of a muscle. What causes a cramp is a subject of much discussion, and poorly understood. A quick check on the web doesn't get at too much about why this contraction occurs.

WHy a cramp? The usual checks: electrolytes, hydration, low carbs, tight muscles to begin with are offered up not as reasons, but of things somehow thought to be related to cramping. Here's an examplary summary of that kind. In this model, the thesis seems to go, the muscles don't have the chemical materials needed to fire in that working limb properly so they effectively rigor mortis up. This rationale for cramp has been more or less tossed out as demonstrated here in 04, and as summarised in this recent BMJ review article. First, on dehydration:

A careful review of the literature did not identify a single published scientific study showing that athletes with acute EAMC are more dehydrated that control athletes (athletes of the same gender, competing in the same race with similar race finishing times). In contrast, there is evidence from four prospective cohort studies showing that dehydration is not associated with EAMC.And on electrolytes (and dehydration):

In summary, dehydration and electrolyte depletion are often considered together (and recently together with muscle fatigue) as the ‘‘triad’’ causing EAMC. The key components of this hypothesis (fig 1) are that electrolyte (mainly sodium) depletion through excessive sweat sodium loss together with dehydration causes EAMC. However, results from prospective cohort studies consistently show that athletes suffering from acute EAMC are not dehydrated, neither do they have disturbances in serum osmolality or serum electrolyte (notably sodium) concentrations. Furthermore, sweat sodium concentrations measured during exercise in 23 reported cases with a past history of EAMC are not higher than those reported in many other studies. Both electrolyte depletion and dehydration are systemic abnormalities, and therefore would result in systemic symptoms, as has been observed in other clinical conditions. However, in EAMC, the symptoms classically are local and are confined to the working muscle groups. Thus, the available evidence to date does not support the hypotheses that electrolyte depletion or dehydration cause EAMC — therefore an alternate hypothesis for the aetiology of EAMC has to be considered.And here's another typical "it's because you didn't stretch right" response - but you'll note the article doesn't raelly say *why* stretching prior to running does or does not do anything for cramp reduction. Indeed, when it comes to running and stretching, the current scene seems to suggest that a stretching program - not necessarily something done prior to running, but just putting this into one's routine - helps running mechanics. That's different. And has nothing to do with a pre-run routine to reduce cramps; as we'll see, stretching is used to respond to a cramp; not prep for one.

Here's another view of cramps by Luke Hoffman that could be written for VFF runners:

According to current theory in the sports science literature (as of 1997), skeletal muscle cramps during exercise probably happen when muscles that are shortened (for example, a calf muscle when your toe is pointed) are repeatedly stimulated. This can happen if your foot is extended, toe pointed, and you keep extending it further. You can actively do this by, for example, running on your toes or doing lots of toe-raises without going down to extend the muscle. What appears to happen is that the muscle gets fatigued, and it doesn't relax well. There is a reflex arc -- made up of the muscle, the nerves carrying signals to the central nervous system (CNS) and the nerves carrying signals from the CNS back to the muscle -- that keeps carrying contraction signals from and to the muscle. This appears to lead to a sustained contraction in the muscle, also known as a cramp.

Stretching (in this case, grabbing your toe and stretching the calf) is about the only thing that breaks this reflex arc signal and stops the cramp when it comes to exercise-induced cases. But the muscle is still fatigued, and the cramp process is easy to re-trigger until the muscle rests for a while. The fatigue-cramp process seems to happen most often in muscles that cross two joints, such as the calf muscle (which crosses the knee and ankle), since the muscle is easy to shorten and continue contracting.

The above describes what might be called "voluntary contraction" - not quite the same as involuntary. If we take the above council about voluntary cramps to bear, however, what should be the case is once a cramp starts, we should stretch it out, and wait for the fatigue to pass from that contraction, and recover, and really stop doing what we were doing - running on the forefoot. Consequently, Pose & VFF runners who run on the forefoot should be cramping all the time. And if we believe work in barefoot running, this is rather how we're designed to run. So, hmm, maybe not.

None of these explanations therefore is complete it seems, to explain cramping we see in the calves that comes on unexpectedly, as lots of well fed, well hydrtated, well electolyted people who stretch still get cramps, and these weird cramps in VFF's in particular.

So why does this cramp only happen *some* of the time - especially if all the typical niceities of cramp avoidance are observed? For me, for instance, it happened first when i started practicing actually bringing the heel of the foot down more (extending the calf) when running, rather than staying up on the forefoot. So, maybe it's not (entirely) about the calves?

Altered Neuromuscular Control. In the research one of the explanations around cramp is: maybe the muscle is just not strong enough to do what is being asked of it, for the duration it's being asked to operate at this level - hence fatiguing - and it's that fatigue that is setting up EAMC: exercise-associated muscle cramping. This hypothesis, also known as "altered neuromuscular control" was first proposed in 1996, so that's how new this stuff is. A key part of this model is that the neuromuscular control issue is located in the SPINE, not at the site of the issue - the site is paying for what's going on at the source.

There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the mechanism for muscle cramping has a neuromuscular basis. Firstly, as has been discussed, voluntary muscle contraction or stimulation of the motor nerve can reliably cause muscle cramping. Secondly, there is evidence from experimental work in human subjects that stimulation of the 1a afferents through electrical stimulation or using the tendon tap (activating the 1a afferents) can induce cramping. Thirdly, it has repeatedly been shown that the most effective treatment for cramping induced in this manner is muscle stretching.

[WHY stretching?] An increase in tension in the Golgi tendon organ during stretching, which will result in increased afferent reflex inhibitory input to the a-motor neuron, is a plausible mechanism to explain why stretching is an effective treatment of cramping. [see Bertolasi and Co., '93]

[...]

There are other possible mechanisms that could alter neuromuscular control at the spinal cord level, and therefore may contribute to the development of EAMC. The first of these is the possibility that muscle injury or muscle damage, resulting from fatiguing exercise, could cause a reflex ‘‘spasm’’, and thereby result in a sustained involuntary contraction. The second possibility is that increased or decreased signals from other peripheral receptors (such as chemically sensitive intramuscular afferents, pressure receptors or pain receptors) could elicit a response from the central nervous system that can alter neuromuscular control of the muscles. These other mechanisms have not been investigated in athletes with EAMC, but would be important to explore in the future.

So in the Pain as Signal to Change perspective, cramps are painful; they are a signal to change. The altered neuromuscular control model suggests, stretch it out and recover. Related work suggests, improve strength/stamina to reduce fatigue and reduce this muscle cramp response. Both have in common that fatigue is causing neural level loss of appropriate control.

So in the Pain as Signal to Change perspective, cramps are painful; they are a signal to change. The altered neuromuscular control model suggests, stretch it out and recover. Related work suggests, improve strength/stamina to reduce fatigue and reduce this muscle cramp response. Both have in common that fatigue is causing neural level loss of appropriate control. Wildly Hypothesising? What's going on when this particular response occurs well before one would think a muscle used to running for miles and miles starts to go all crampy?

In

In Z-Health, Eric Cobb translates this fear response into the nervous system's job to perceive threat or no threat: if there's a perception of threat, the system starts to shut down (example in arthrokinetic reflex). What might be the threat ocuring in VFF ocaisional calve cramping? The system may be literally putting on the breaks to what it perceives as a threatening to it's well being practice.

It's easy to see that if the nervous system perceives that the task - going at a particular speed in a particular way - is causing part of the system to be over-taxed, it's going to respond to that as a threat or non-optimal situation, and if it takes pain to get change, well, whatever it takes.

Personal Experience. Taking a Z-Health approach to this experience, i think i've learned to become more alert to any pain signal my bod sends up in an athletic effort. So in this case, if and when these cramps begin, they usually start with a very mild "uh oh" twinge of "about to turn to rock if you don't respond."

There are two simple things that z-health suggests for rehabbing a movement with the cue of "never move into pain:"

- reduce the range of motion

- reduce the load

Guided by the Nose: run to pace inhalation. Another technique i've been using and coaching to help head off cramps and adapt to barefooting generally is to explore gaiting running speed with ability to stay breathing in through one's nose. If running at a clip where i have to mouth breath, i slow it down (i find if i hit that level, it's pretty hard to get it back to nose inhaling). This approach is just one way at least some of the time to practice running reps quality rather than overdriving the other parts of the system.

Deeper Tune Up: Starting from the Source

So we've seen one theory in the research is around muscular fatigue inducing EAMC; getting stronger in those areas where muscles cramped seemed to help. In one study. That's great. Another possibility - that can lead to faster fatigue - is if there's some kind of issue in one's movement that is causing perhaps other muscles to compensate for other weaknesses, and causing fatigue/pain/signaling in the calves faster that should happen for that group. So while a solution may be to do extra strength work, maybe a faster solution may actually be to look at one's movement as a whole.

In other words, the calves may be plenty strong IF everything else is firing up appropriately, but they may be being asked to super compenate for other stuff, that if those other movement issues were addressed, wouldn't cause the problem.

There's value therefore in (a) having a movement assessment and (b) practicing dynamic joint mobility and sensory-motor work to ensure great movement, and ability to maintain great, clean movement.

Summary: Avoiding Running Cramps in VFF's

Based on the latest research, EAMC cramps are about temporary loss of clear neuromuscular control. The best model so far to explain this effect is fatigue. A known way to work out a cramp is to lengthen the muscle. There may however be other approaches that just haven't been researched that also seem to work. The hypothesis here is that these approaches are dealing with neurological signaling, too, taking advantage of the sensory-motor system.

Some pragmatic responses therefore if cramp occurs are:

During a Run: Assuming one is not dehydrated, de-electrolyted, or have squirrels biting their calves while running,

- As soon as a cramp (pain) starts, change something - gait, speed, whatever; if that doesn't work, stop what you're doing.

- consider rather than (just) stretching, doing mobility/sensory-motor work.

And before That

Consider a movement assessment to check for what Gray Cook calls "weak links" so as not to build strength on top of dysfunction.

Let me know what works for you.

Citations

Schwellnus, M. (2008). Cause of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps (EAMC) -- altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43 (6), 401-408 DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.050401

OHMAN, A. (2005). The role of the amygdala in human fear: Automatic detection of threat Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30 (10), 953-958 DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.019

Bertolasi L, De Grandis D, Bongiovanni LG, Zanette GP, & Gasperini M (1993). The influence of muscular lengthening on cramps. Annals of neurology, 33 (2), 176-80 PMID: 8434879

Wagner, T. (2009). Strengthening and Neuromuscular Reeducation of the Gluteus Maximus in a Triathlete With Exercise-Associated Cramping of the Hamstrings Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy DOI: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3110

Caplan N, Rogers R, Parr MK, & Hayes PR (2009). The effect of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and static stretch training on running mechanics. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association, 23 (4), 1175-80 PMID: 19528850

Schwellnus, M. (2004). Serum electrolyte concentrations and hydration status are not associated with exercise associated muscle cramping (EAMC) in distance runners British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38 (4), 488-492 DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.007021

Schwellnus MP (2007). Muscle cramping in the marathon : aetiology and risk factors. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 37 (4-5), 364-7 PMID: 17465609Related Sources

Schwellnus, M. (2008). Cause of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps (EAMC) -- altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43 (6), 401-408 DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.050401

Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

ck-fms,

cramps,

movement assessment,

movement screen,

muscle cramps,

neurology,

spine,

z-health

Thursday, May 6, 2010

Pull Up Happiness: Great Coaching can make so much difference.

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

One of the best parts of the certifications the RKC runs is that, as part of the training, after learning the drills, we practice corrections for these drills. Pavel asks for one candidate who may be working on a particular issue in a given move. and then asks for another candidate to articulate what they're seeing and what corrections they might run. It's in no small part because of these mini case studies in applied work that RKC's leave well prepared to teach and what makes the RKC such a potent teaching paradigm.

One of the best parts of the certifications the RKC runs is that, as part of the training, after learning the drills, we practice corrections for these drills. Pavel asks for one candidate who may be working on a particular issue in a given move. and then asks for another candidate to articulate what they're seeing and what corrections they might run. It's in no small part because of these mini case studies in applied work that RKC's leave well prepared to teach and what makes the RKC such a potent teaching paradigm.

As for being a victim in these cases, there is only a benefit and no shame in being so pointed out: if you're a victim for a Pavel crit session, you have the opportunity to get incredible feedback on your form from a world-leading coach.

At the Feb 2010 RKC II critique session where i was humbly holding the pull up bar for RKCII Strong Gal Nikki Shlosser, who presses 24s like they were 12s. sheesh,

Brett Jones said, "why not have mc do one?"

While I had had the privilege a few times that weekend for some corrective strategies, this was the best: a one on one PU workshop with Pavel, featuring excellent feedback from the floor from both Team Lead Paul Daniels (who uses the gently thrust the foot in the stomach of victim while pulling on arms to correct a windmill technique) and RKC II beast tamer KC Reitter - oh, and quite a bit from Pavel, too (each time i finished a pull up, got feedback, and thinking wow, that was great, and to go back to sit down, Pavel said "don't go away, com mc; we're not finished [insert discussion of technique improvements]...Again now, please [insert pull up here]. What else would you say comrades?" - awesome).

What can i say? Repete apres le model...

While i have a long way to go (as you can see), and others are way stronger in this event than i (including the inspirational two times tactical strength women's champ, UK'er RKC Angela Craig ), i love the Pull Up. And i dig Pavel's coaching - the latter being why i travelled across the ocean to do the RKC II. And wow, there they were together! Great great tips to improve something i love to do. Thanks again Brett Jones for that casual "why not..." Funny how those things can take us by surprise eh? Quel Gateau, Quel Surprise! Now i'm getting all vaklempt about it, so you'll just have to excuse me....happy happy joy joy.

mc

PS -update

Note my head over the bar? that first one - that's me looking up with joy, and two, that's an end move i have to stop - it's me sticking my neck over the bar at the end deliberately - since part of the RKC II test is to make cleat the chin is over the bar. But there are costs for this if one does it on the way up. Mike T. Nelson's video, that he references in the comments on this post, shows why clearly:

Related Posts

One of the best parts of the certifications the RKC runs is that, as part of the training, after learning the drills, we practice corrections for these drills. Pavel asks for one candidate who may be working on a particular issue in a given move. and then asks for another candidate to articulate what they're seeing and what corrections they might run. It's in no small part because of these mini case studies in applied work that RKC's leave well prepared to teach and what makes the RKC such a potent teaching paradigm.

One of the best parts of the certifications the RKC runs is that, as part of the training, after learning the drills, we practice corrections for these drills. Pavel asks for one candidate who may be working on a particular issue in a given move. and then asks for another candidate to articulate what they're seeing and what corrections they might run. It's in no small part because of these mini case studies in applied work that RKC's leave well prepared to teach and what makes the RKC such a potent teaching paradigm.As for being a victim in these cases, there is only a benefit and no shame in being so pointed out: if you're a victim for a Pavel crit session, you have the opportunity to get incredible feedback on your form from a world-leading coach.

At the Feb 2010 RKC II critique session where i was humbly holding the pull up bar for RKCII Strong Gal Nikki Shlosser, who presses 24s like they were 12s. sheesh,

Brett Jones said, "why not have mc do one?"

While I had had the privilege a few times that weekend for some corrective strategies, this was the best: a one on one PU workshop with Pavel, featuring excellent feedback from the floor from both Team Lead Paul Daniels (who uses the gently thrust the foot in the stomach of victim while pulling on arms to correct a windmill technique) and RKC II beast tamer KC Reitter - oh, and quite a bit from Pavel, too (each time i finished a pull up, got feedback, and thinking wow, that was great, and to go back to sit down, Pavel said "don't go away, com mc; we're not finished [insert discussion of technique improvements]...Again now, please [insert pull up here]. What else would you say comrades?" - awesome).

What can i say? Repete apres le model...

While i have a long way to go (as you can see), and others are way stronger in this event than i (including the inspirational two times tactical strength women's champ, UK'er RKC Angela Craig ), i love the Pull Up. And i dig Pavel's coaching - the latter being why i travelled across the ocean to do the RKC II. And wow, there they were together! Great great tips to improve something i love to do. Thanks again Brett Jones for that casual "why not..." Funny how those things can take us by surprise eh? Quel Gateau, Quel Surprise! Now i'm getting all vaklempt about it, so you'll just have to excuse me....happy happy joy joy.

mc

PS -update

Note my head over the bar? that first one - that's me looking up with joy, and two, that's an end move i have to stop - it's me sticking my neck over the bar at the end deliberately - since part of the RKC II test is to make cleat the chin is over the bar. But there are costs for this if one does it on the way up. Mike T. Nelson's video, that he references in the comments on this post, shows why clearly:

Related Posts

- Prepping for the RKC Cert - the other stuff

- Interview with Asha Wagner - pressing, pulling and pistoling the 24

- Michael Castrogiovanni Interview - kettlebell pairs tossing.

- b2d Kettlebell Index

- PULL UPS - HOW TO resource guide

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

Ab Exercise Surprise - Moves you mayn't have suspected require (lots of) abs/core

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

Six pack lust. So many workout programs are sold on the promise of delivering visible abs. As we've talked about before, a 6 pack is largely about body fat %: get it below 10 if you're a guy, 16 if you're a gal, and voila: visible abs. But what if you want stonking great abs? Then work them in traditional isolation patterns of crunches, as per these approaches for more ab strength/hypertrophy? Well, you could. There are some interesting programs to do that and folks like powerlifters and olympic lifters definitely have them - for a specific reason - as part of their workouts. But you may find that you are already working your abs sufficiently to meet your goals - if you plan the rest of your program right. And on the high side, you'll be able to show off some beautiful skills that simultaneously work the abs.

Six pack lust. So many workout programs are sold on the promise of delivering visible abs. As we've talked about before, a 6 pack is largely about body fat %: get it below 10 if you're a guy, 16 if you're a gal, and voila: visible abs. But what if you want stonking great abs? Then work them in traditional isolation patterns of crunches, as per these approaches for more ab strength/hypertrophy? Well, you could. There are some interesting programs to do that and folks like powerlifters and olympic lifters definitely have them - for a specific reason - as part of their workouts. But you may find that you are already working your abs sufficiently to meet your goals - if you plan the rest of your program right. And on the high side, you'll be able to show off some beautiful skills that simultaneously work the abs.

Known Compounds We know that the abs get worked as part of many "compound" exercises - that is, exercises that work multiple muscle groups at once, and in particular, workouts that work the core: the hip, pelvic, lumbar areas. A kettlebell swing is a great example of a compound exercise that hits the core, getting both upper body, middle and lower body. A turkish get up (as worked through in Kalos Sthenos for example) requires lots of ab work to complete that getting up part. The more traditional squat, likewise. A push up, a pull up (even a pull up, here's a how to resource), all engage the fabulous core, of which the abs are a core part. But these aren't the only ones.

Known Compounds We know that the abs get worked as part of many "compound" exercises - that is, exercises that work multiple muscle groups at once, and in particular, workouts that work the core: the hip, pelvic, lumbar areas. A kettlebell swing is a great example of a compound exercise that hits the core, getting both upper body, middle and lower body. A turkish get up (as worked through in Kalos Sthenos for example) requires lots of ab work to complete that getting up part. The more traditional squat, likewise. A push up, a pull up (even a pull up, here's a how to resource), all engage the fabulous core, of which the abs are a core part. But these aren't the only ones.

What i'd like to share here are a few exercises that shake up the abs and may be a bit of a surprise to find that they do. What i'd like to ask is to hear from you, if these or any particular moves have surprised you in how they hit your core.

Renegade Row.

The renegade row (detailed here) is a powerful exercise, demanding a lot of rigidness through the middle - like a plank - to maintain form. But unlike a plank, the renegade row is a lovely full body movement that requires a lot of sensory-motor integration and small movement firing.

The renegade row (detailed here) is a powerful exercise, demanding a lot of rigidness through the middle - like a plank - to maintain form. But unlike a plank, the renegade row is a lovely full body movement that requires a lot of sensory-motor integration and small movement firing.

You'll find that the obliques in particular are hit happily by this one - all the while working the chest, delts, lower back, butt - well lots of full on core and upper body too.

Windmill

Windmill

The windmill is a combination press and bend movement.

This one has been a big surprise for me, again working the obliques with light loads and lots of reps, The usual focus of windmill is hip/pelvis stability and shoulder stability, but goodness, this will fire up the middle - again the obliques, but in a way different and lower down than the Renegade Row

Flexed Arm Hang

I like pull ups. I do pull ups. A pull up is a part of the RKC II test - doesn't show up on the RKC I cert test. I looked at the test for the gals for the HKC cert and noticed that it's a flexed arm hang hold for 15 sec - don't even have to pull up to the bar.

A flexed arm hang means hanging onto a pullup bar so that the chin clears the top of the bar.

As a kid, one of the tests for a kid to get a gold fitness medal was a 60sec flexed-arm hang. For a gal who does pull ups, this is gonna be easy peasy.

Er, no, it wasn't. The first thing to start to feel it, beside the shake in my arms? My abs. Oh man.

So y'all out there who do pull ups? Well i got something to say to you: don't go for second best, baby: put your pull up to the test. Make them express how your abs feel then you'll know they're made of steal.

In other words, next time doing a pull up? Stop at the top for 15 secs (or longer, like 70 as in the USMC test) and see how that isometric hold works for you. It may just be a surprise.

Skipping

Ok, this is perhaps my biggest ab surprise. After watching Andrea U Shi Chang skip non-stop last summer effortlessly for well over ten minutes, and listening to Rannoch Donald of Simple Strength talk about the many values of skipping (here's a discussion over at b2d on facebook), i've thought what the heck - especially for travel. Where do i feel it? Mainly? Yes, abs. That was a surprise.

And if you're interested in giving skipping a go, it's a skill, and one to think of initially in terms of short sets. It can cause DOMS in the areas of the calf muscles not generally worked - even by bicycle couriers. But as said, more than that, abs will get it good too.

In the facebook discussion, Rannoch points to a couple sources from bodyweight maestro Ross Enemait: Part 1, and Part 2 of his tutorials are here. And here's some inspiration:

Variety is the Spice of Muscle Life

Each of these movements hits the abs in a slightly different way, and that's good - to be able to get the obligues through pulls and rotaion, and the abs through say static holds and higher reps.

What has surprised me is just the fact that these moves have been able to show me the next day the degree to which these are hitting the abs in new ways. Why the surprise? I do a lot of swings with various load kb's (eg, running the bells). Recently i was able to start adding hanging leg raise work to my routine (until my shoulder said it wanted a break from pull ups) - that's supposed to be a big ab challenge. i didn't really feel it there the next day, either. Which suggests that HLR's may be at this point more about technique work than strength development - afterall, i ain't doing 20 in a row. So, not a new load and not a new enough move to make the abs say "new work."

But skipping? Skipping? for like 70-110 reps? That makes my abs talk to me the day after?

So, here's the thing, muscles adapt to movements by developing new muscle fiber firing patterns to support loads and movements. The more these are practiced, the more familiar, the more literally engrained they become. Change the load; change the movement involving that muscle, and the body has to put effort into learning a new process.

When we feel that bit of next day challenge (aka DOMS) in a muscle group that's used to being worked one way, we know we're getting it in a new way. That's a good thing: it means our bodies and minds are mapping new skills and adapting in new ways - in this case part of the new adaptation is strength. And as posted recently, hypertrophy starts with rep one. So that's good too.

I'm not saying at all the desire here is to trigger a DOMS response; it's just a way to know that a muscle has been hit in a new way - and that can mean either a new move or a new load. Light DOMS is a way to know that that has been the case.

Potential Trivia:

In DOMS, it's generally the eccentric part of an action that causes the DOMS experience, which is why researchers testing DOMS will often have participants walks backwards down an elevated treadmill.

In the crunch, while most of us usually focus on the energy to contract in, the science suggests it's the uncurling - controlling the eccentric contraction that causes the DOMS response.

Recently we also looked at the role of these eccentrics in helping address tendinopathies - might there be a relationship?

So here's a question:

Above are four examples of Ab Surprises.

What moves have hit your abs/obliques by surprise - when perhaps you mayn't have thought the move was going anywhere near your midsection? Do you still do that move?

Look forward to hearing from you,

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Six pack lust. So many workout programs are sold on the promise of delivering visible abs. As we've talked about before, a 6 pack is largely about body fat %: get it below 10 if you're a guy, 16 if you're a gal, and voila: visible abs. But what if you want stonking great abs? Then work them in traditional isolation patterns of crunches, as per these approaches for more ab strength/hypertrophy? Well, you could. There are some interesting programs to do that and folks like powerlifters and olympic lifters definitely have them - for a specific reason - as part of their workouts. But you may find that you are already working your abs sufficiently to meet your goals - if you plan the rest of your program right. And on the high side, you'll be able to show off some beautiful skills that simultaneously work the abs.

Six pack lust. So many workout programs are sold on the promise of delivering visible abs. As we've talked about before, a 6 pack is largely about body fat %: get it below 10 if you're a guy, 16 if you're a gal, and voila: visible abs. But what if you want stonking great abs? Then work them in traditional isolation patterns of crunches, as per these approaches for more ab strength/hypertrophy? Well, you could. There are some interesting programs to do that and folks like powerlifters and olympic lifters definitely have them - for a specific reason - as part of their workouts. But you may find that you are already working your abs sufficiently to meet your goals - if you plan the rest of your program right. And on the high side, you'll be able to show off some beautiful skills that simultaneously work the abs. What i'd like to share here are a few exercises that shake up the abs and may be a bit of a surprise to find that they do. What i'd like to ask is to hear from you, if these or any particular moves have surprised you in how they hit your core.

Renegade Row.

The renegade row (detailed here) is a powerful exercise, demanding a lot of rigidness through the middle - like a plank - to maintain form. But unlike a plank, the renegade row is a lovely full body movement that requires a lot of sensory-motor integration and small movement firing.

The renegade row (detailed here) is a powerful exercise, demanding a lot of rigidness through the middle - like a plank - to maintain form. But unlike a plank, the renegade row is a lovely full body movement that requires a lot of sensory-motor integration and small movement firing.You'll find that the obliques in particular are hit happily by this one - all the while working the chest, delts, lower back, butt - well lots of full on core and upper body too.

Windmill

WindmillThe windmill is a combination press and bend movement.

This one has been a big surprise for me, again working the obliques with light loads and lots of reps, The usual focus of windmill is hip/pelvis stability and shoulder stability, but goodness, this will fire up the middle - again the obliques, but in a way different and lower down than the Renegade Row

Flexed Arm Hang

I like pull ups. I do pull ups. A pull up is a part of the RKC II test - doesn't show up on the RKC I cert test. I looked at the test for the gals for the HKC cert and noticed that it's a flexed arm hang hold for 15 sec - don't even have to pull up to the bar.

A flexed arm hang means hanging onto a pullup bar so that the chin clears the top of the bar.

As a kid, one of the tests for a kid to get a gold fitness medal was a 60sec flexed-arm hang. For a gal who does pull ups, this is gonna be easy peasy.

Er, no, it wasn't. The first thing to start to feel it, beside the shake in my arms? My abs. Oh man.

So y'all out there who do pull ups? Well i got something to say to you: don't go for second best, baby: put your pull up to the test. Make them express how your abs feel then you'll know they're made of steal.

In other words, next time doing a pull up? Stop at the top for 15 secs (or longer, like 70 as in the USMC test) and see how that isometric hold works for you. It may just be a surprise.

Skipping

Ok, this is perhaps my biggest ab surprise. After watching Andrea U Shi Chang skip non-stop last summer effortlessly for well over ten minutes, and listening to Rannoch Donald of Simple Strength talk about the many values of skipping (here's a discussion over at b2d on facebook), i've thought what the heck - especially for travel. Where do i feel it? Mainly? Yes, abs. That was a surprise.

And if you're interested in giving skipping a go, it's a skill, and one to think of initially in terms of short sets. It can cause DOMS in the areas of the calf muscles not generally worked - even by bicycle couriers. But as said, more than that, abs will get it good too.

In the facebook discussion, Rannoch points to a couple sources from bodyweight maestro Ross Enemait: Part 1, and Part 2 of his tutorials are here. And here's some inspiration:

Variety is the Spice of Muscle Life

Each of these movements hits the abs in a slightly different way, and that's good - to be able to get the obligues through pulls and rotaion, and the abs through say static holds and higher reps.

What has surprised me is just the fact that these moves have been able to show me the next day the degree to which these are hitting the abs in new ways. Why the surprise? I do a lot of swings with various load kb's (eg, running the bells). Recently i was able to start adding hanging leg raise work to my routine (until my shoulder said it wanted a break from pull ups) - that's supposed to be a big ab challenge. i didn't really feel it there the next day, either. Which suggests that HLR's may be at this point more about technique work than strength development - afterall, i ain't doing 20 in a row. So, not a new load and not a new enough move to make the abs say "new work."

But skipping? Skipping? for like 70-110 reps? That makes my abs talk to me the day after?

So, here's the thing, muscles adapt to movements by developing new muscle fiber firing patterns to support loads and movements. The more these are practiced, the more familiar, the more literally engrained they become. Change the load; change the movement involving that muscle, and the body has to put effort into learning a new process.

When we feel that bit of next day challenge (aka DOMS) in a muscle group that's used to being worked one way, we know we're getting it in a new way. That's a good thing: it means our bodies and minds are mapping new skills and adapting in new ways - in this case part of the new adaptation is strength. And as posted recently, hypertrophy starts with rep one. So that's good too.

I'm not saying at all the desire here is to trigger a DOMS response; it's just a way to know that a muscle has been hit in a new way - and that can mean either a new move or a new load. Light DOMS is a way to know that that has been the case.

Potential Trivia:

In DOMS, it's generally the eccentric part of an action that causes the DOMS experience, which is why researchers testing DOMS will often have participants walks backwards down an elevated treadmill.

In the crunch, while most of us usually focus on the energy to contract in, the science suggests it's the uncurling - controlling the eccentric contraction that causes the DOMS response.

Recently we also looked at the role of these eccentrics in helping address tendinopathies - might there be a relationship?

So here's a question:

Above are four examples of Ab Surprises.

What moves have hit your abs/obliques by surprise - when perhaps you mayn't have thought the move was going anywhere near your midsection? Do you still do that move?

Look forward to hearing from you,

mc Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Monday, May 3, 2010

Occlusion Training: Tightening up everything we don't know about Hypertrophy

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

If we asked someone "what should i do to build muscle" probably not a lot of people would say "cut off the blood flow to a working limb." Turns out though, that this latter kind of work - called occlusion training, or blood flow restriction (BFR) - has proven a powerful technique for inducing hypertrophy at very low loads (10-30% of a 1RM). While it's mainly been explored as a rehab technique to help accelerate recovery, some researchers have been looking at it as an approach in regular training. What, then, are the pro's and con's of this technique for training? And what are we learning about the mystery that is hypertrophy from studying the phenomena of occlusion for hypertrohhy strength?

If we asked someone "what should i do to build muscle" probably not a lot of people would say "cut off the blood flow to a working limb." Turns out though, that this latter kind of work - called occlusion training, or blood flow restriction (BFR) - has proven a powerful technique for inducing hypertrophy at very low loads (10-30% of a 1RM). While it's mainly been explored as a rehab technique to help accelerate recovery, some researchers have been looking at it as an approach in regular training. What, then, are the pro's and con's of this technique for training? And what are we learning about the mystery that is hypertrophy from studying the phenomena of occlusion for hypertrohhy strength?

These questions are addressed in an excellent review of occlusion research from 2008 called " Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise?"

Two of the highlights of the paper (at least for me) -the review of hypertrophy models such as they are and a possible rationale for the Pump in bodybuilding circles.

Overview on the (un)Known of Muscle Building

The authors go through an amazing job of investigating the known models of hypertrophy - and all that we dont know about it - to see where occlusion training may fit in with existing models. Heck, in order to understand what role occlusion plays, we need to have some sense of the depth and breadth of the puddle it's playing in.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Not just hormones, the reviewers look at other factors too - like mechano checmical. THat means that maybe the calcium involved in the actin/myosin bridge that enables contractions is a key to what's really important for hypertrophy - but so far there aren't studies looking at these responses in occlusion, so we have no comparison.

This review is great for myth busting. In other words, its review of what we can actually point to and say "that's what casues muscle growth" shows us what we know is so small, it's really exciting. Why is being able to say "but we don't know if that's what's doing it" exciting? One, it means we're starting to know what's going on in more detail to be able to say we don't know and two, it means in any discussion about somebody saying this is WHY this works (like why the pump "works") we can be pretty confident in knowing they maybe shouldn't be so confident.

It may seem a fine point, but work like this also lets us continue to say that "if you do this protocol, you'll get big" - assuming it's been tested on lots of athletes of various types. What we cannot say with the same confidence is WHY if we follow that protocol we're getting big.

I recommend the full first half of the article just for this review of the state of the art (as of 2008) on hypertrophy.

SO where does this get us then with occlusion and hypertrophy?

First a few words about occlusion training - what is it?

Occlusion training goes by a bunch of names: kaatsu training, occlusion, Blood Flow Restriction (BFR), ishemic training. Occlusion generally means to obstruct or block or even hide something (from view). In the case of muscle work, the blood flow is obstructed, usually by a tournequette of some kind. Ischemia is sort of the technical term for blood flow restriction - to the heart or other body tissue -as a result of some type of block (or occlusion).

Protocols - often seem to involve tournequetting the working limb, then using loads of 10-30% of a 1RM, usually lots of reps, very low rest, until fatigue hits. The results in strength gains are similar to working sets with 80% 1RMs.

The main benefit has been seen in rehab, getting a person who's too weak to work at heavy levels, back on their feet again. There's even been consideration of the use of this kind of training for astraunauts who, following Woolfs' and Davis's law do tend to lose it from not using it - their muscle that is.

So, we can start to see with results like this, it would be interesting to understand how low loads with a cuff can cause strength gains equivalent to 80% of a 1RM

Is It Safe?

One of the biggie first questions people have about occlusion is (well, what was yours>) - is - is it safe? The authors respond that by saying they looked at 13 studies with thousands of trials - and even in the one where the forearm was completely occluded for 20mins, there were no measurable ill effects.

Most sessions last only 5-10 mins, and are not full, but partial occlusion.

Likewise, i was reading a 2010 study that wanted to see if thrombosis symptoms would occur in healthy participants - another concern about occlusion - and nothing close to that effect was measured. So from these typical kinds of fears, no such effects it seems have been measured.

The one side effect "acute muscle pain" - i think this means similar to the burn sensation some folks get when going too far in a set. That's common with the "to fatigue" type training used in occlusion. DOMS is also common in the first few bouts. The authors suggest that with these cautions in mind "training combined with ischemia clearly requires a high degree of motivation from the trainee, especially if performed with a high level of effort."

Will that be Wide or Narrow?

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

Last year i looked at a study that just tied up the lower limbs with wide wraps. Important to note that the cuffs these folks are describing in the research reviews can have the pressure adjusted with the cuff to exact mmHg, similar to a blood pressure cuff.

I make no recommendations about whether it's better to use a proper occlusion cuff or just wrap up a limb; i only note that the places in Japan that have the most experience with this approach use Katsu cuffs - cuffs that enable control of pressure.

Is a Tournequette Even Necessary?

This is my favorite part of the paper because i think there's a link between what is described here, and what is discussed with the Pump (b2d overview here). See what you think.

First the authors point out that studies show the effect of an occlusion cuff is erased once loads get up to 40-60% load. What's interesting is that work using research's favorite - the leg extension - showed that even without a cuff, loads as low as 20% could induce "ischemic pain" - like that's a good thing.

The authors hypothesize that there are ways to get a low load ischemic effect without a cuff by doing the following: partials

So this is where my Pump query comes in: the Pump - if one is not overtraining and under nourished - is easy to achieve by using lots of reps with light loads, until one's arms or related feel like they're so full of blood they can't move. Sounds like kaatsu work.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.

What i'm intrigued by is that there seems to be a lot of circumstantial evidence to say that ishemia induced with low loads develops hypertrophy - but if anyone tries to say "and here's why that is" - and they start talking about NO supplements and flushing and who knows what all - you can pretty confidently say, well, based on what research?

In other words, there's a relationship it looks like, but what the actual mechanism is, we don't entirely know. Mybe it's fatiguing out type one and bringing on type II, maybe its IGF-1 goes up and myostatin goes down. Maybe it's mTOR levels. They're all in the soup. But what's cause and what's conincidence - ain't clear. But i sure as heck ain't gonna say the pump is a myth - just the explanations for it so far are pretty mythical.

To Cuff or Not to Cuff

One might think that just going for this kind of non-cuff'd based ischemia (blood pooling; can't flow back) is better than cuff based. Here's what the authors think:

What about the Dose?

To summarise a great long section of this paper, the results are not in for normal training about what the optimal frequence, volume, intensity is for optimal hypertrophic effect using occlusion.

The authors make a great note that not all ischemic training results in strength gains. For some reason, cycling isn't great for occlusion and strength development. On the other hand walk training is one of the big successes of occlusion work, and of course stength training - the short bursts of activity - is where the biggest benefit seems to be. Whether therefore the ratio between ischemia and reperfusion is key here, we just don't know but it seems to be a factor.

Will it Blend

So if we're not rehabbing, and with all the unknowns about dose, is it appropriate to put occlusion training into the mix of a regular strength program with "heavy" resistance.

I dunno.

The authors focus on work that's looked at two great benefits of heavy resistance training: bone mineral density and tendon stiffness.

In both cases lighter load work has been shown to have less of an effect on these factors. So - for ones bones, heavy resistance is a bonus - but then, so is stop and start action. For tendons, however, it seems that volume is also a key factor in enhancing stiffness (MTC descibed here - doesn't mean anything about flexibility, but about load, really)

In other words, while occlusion may not bring on the benefits of heavy resistance, there are other ways than heavy work to enhance these benefits so playing with ischemia may be useful for strength development.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome.  Trainer par excellance Roland Fisher introduced me to the timed sets of Huge in a Hurry

Trainer par excellance Roland Fisher introduced me to the timed sets of Huge in a Hurry 's Chad Waterbury. Very simple: get a weight at the end of a session where you can do 20 reps, and as soon as the fast tempo drops to complete the set, drop the weight, go for another 20. By using time as the marker, there's no way to get to fatigue and form failure. One heck of a pump, too. Thus, one has done their heavy work, and uses the occlusion level sets for a finisher. I love it. Your mileage may vary. See what you find.

's Chad Waterbury. Very simple: get a weight at the end of a session where you can do 20 reps, and as soon as the fast tempo drops to complete the set, drop the weight, go for another 20. By using time as the marker, there's no way to get to fatigue and form failure. One heck of a pump, too. Thus, one has done their heavy work, and uses the occlusion level sets for a finisher. I love it. Your mileage may vary. See what you find.

Wrap UP - sans wraps even

And speaking of finisher, the authors wrap up with the following. The first sentence for me is key:

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too.

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too.

The point is, i guess, that as this article started, just when we think we know something who'd a thought that strength can be aided by counter-intuitive actions like restricting blood supply? where does that map to evolution?

If nothing else, occlusion work shows us that we are complex systems with more than one path to create an effect.

Related Resources

Citations:

These questions are addressed in an excellent review of occlusion research from 2008 called " Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise?"

Two of the highlights of the paper (at least for me) -the review of hypertrophy models such as they are and a possible rationale for the Pump in bodybuilding circles.

Overview on the (un)Known of Muscle Building

The authors go through an amazing job of investigating the known models of hypertrophy - and all that we dont know about it - to see where occlusion training may fit in with existing models. Heck, in order to understand what role occlusion plays, we need to have some sense of the depth and breadth of the puddle it's playing in.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all. Not just hormones, the reviewers look at other factors too - like mechano checmical. THat means that maybe the calcium involved in the actin/myosin bridge that enables contractions is a key to what's really important for hypertrophy - but so far there aren't studies looking at these responses in occlusion, so we have no comparison.

This review is great for myth busting. In other words, its review of what we can actually point to and say "that's what casues muscle growth" shows us what we know is so small, it's really exciting. Why is being able to say "but we don't know if that's what's doing it" exciting? One, it means we're starting to know what's going on in more detail to be able to say we don't know and two, it means in any discussion about somebody saying this is WHY this works (like why the pump "works") we can be pretty confident in knowing they maybe shouldn't be so confident.

It may seem a fine point, but work like this also lets us continue to say that "if you do this protocol, you'll get big" - assuming it's been tested on lots of athletes of various types. What we cannot say with the same confidence is WHY if we follow that protocol we're getting big.

I recommend the full first half of the article just for this review of the state of the art (as of 2008) on hypertrophy.

SO where does this get us then with occlusion and hypertrophy?

First a few words about occlusion training - what is it?

Occlusion training goes by a bunch of names: kaatsu training, occlusion, Blood Flow Restriction (BFR), ishemic training. Occlusion generally means to obstruct or block or even hide something (from view). In the case of muscle work, the blood flow is obstructed, usually by a tournequette of some kind. Ischemia is sort of the technical term for blood flow restriction - to the heart or other body tissue -as a result of some type of block (or occlusion).

Protocols - often seem to involve tournequetting the working limb, then using loads of 10-30% of a 1RM, usually lots of reps, very low rest, until fatigue hits. The results in strength gains are similar to working sets with 80% 1RMs.

The main benefit has been seen in rehab, getting a person who's too weak to work at heavy levels, back on their feet again. There's even been consideration of the use of this kind of training for astraunauts who, following Woolfs' and Davis's law do tend to lose it from not using it - their muscle that is.

So, we can start to see with results like this, it would be interesting to understand how low loads with a cuff can cause strength gains equivalent to 80% of a 1RM

Is It Safe?

One of the biggie first questions people have about occlusion is (well, what was yours>) - is - is it safe? The authors respond that by saying they looked at 13 studies with thousands of trials - and even in the one where the forearm was completely occluded for 20mins, there were no measurable ill effects.

Most sessions last only 5-10 mins, and are not full, but partial occlusion.

Likewise, i was reading a 2010 study that wanted to see if thrombosis symptoms would occur in healthy participants - another concern about occlusion - and nothing close to that effect was measured. So from these typical kinds of fears, no such effects it seems have been measured.

The one side effect "acute muscle pain" - i think this means similar to the burn sensation some folks get when going too far in a set. That's common with the "to fatigue" type training used in occlusion. DOMS is also common in the first few bouts. The authors suggest that with these cautions in mind "training combined with ischemia clearly requires a high degree of motivation from the trainee, especially if performed with a high level of effort."

Will that be Wide or Narrow?

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.Last year i looked at a study that just tied up the lower limbs with wide wraps. Important to note that the cuffs these folks are describing in the research reviews can have the pressure adjusted with the cuff to exact mmHg, similar to a blood pressure cuff.

I make no recommendations about whether it's better to use a proper occlusion cuff or just wrap up a limb; i only note that the places in Japan that have the most experience with this approach use Katsu cuffs - cuffs that enable control of pressure.

Is a Tournequette Even Necessary?

This is my favorite part of the paper because i think there's a link between what is described here, and what is discussed with the Pump (b2d overview here). See what you think.

First the authors point out that studies show the effect of an occlusion cuff is erased once loads get up to 40-60% load. What's interesting is that work using research's favorite - the leg extension - showed that even without a cuff, loads as low as 20% could induce "ischemic pain" - like that's a good thing.

The authors hypothesize that there are ways to get a low load ischemic effect without a cuff by doing the following: partials

Other quadriceps exercises can also be modified to achieve intramuscular restriction of blood flow. During closed kinetic chain exercises such as the squat and the leg press, the force demands of the movement dictate that the electrical activity of the quadriceps is high at flexed knee angles (90°–100°) and low near full-knee extension (Andersen et al., 2006). If the range of motion instead is limited to between ∼50° and 100° of flexion, the muscle activity remains fairly high throughout the movement and intramuscular occlusion is thus more likely to occur.The goal of going for ischemia with low loads is to get the benefit of heavier loads without having to use heavier loads that perhaps could not be taken to the given rep level.

So this is where my Pump query comes in: the Pump - if one is not overtraining and under nourished - is easy to achieve by using lots of reps with light loads, until one's arms or related feel like they're so full of blood they can't move. Sounds like kaatsu work.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.