Showing posts with label strength training. Show all posts

Showing posts with label strength training. Show all posts

Monday, May 3, 2010

Occlusion Training: Tightening up everything we don't know about Hypertrophy

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

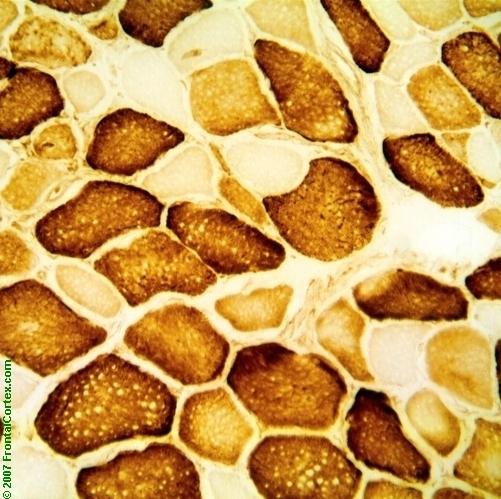

If we asked someone "what should i do to build muscle" probably not a lot of people would say "cut off the blood flow to a working limb." Turns out though, that this latter kind of work - called occlusion training, or blood flow restriction (BFR) - has proven a powerful technique for inducing hypertrophy at very low loads (10-30% of a 1RM). While it's mainly been explored as a rehab technique to help accelerate recovery, some researchers have been looking at it as an approach in regular training. What, then, are the pro's and con's of this technique for training? And what are we learning about the mystery that is hypertrophy from studying the phenomena of occlusion for hypertrohhy strength?

If we asked someone "what should i do to build muscle" probably not a lot of people would say "cut off the blood flow to a working limb." Turns out though, that this latter kind of work - called occlusion training, or blood flow restriction (BFR) - has proven a powerful technique for inducing hypertrophy at very low loads (10-30% of a 1RM). While it's mainly been explored as a rehab technique to help accelerate recovery, some researchers have been looking at it as an approach in regular training. What, then, are the pro's and con's of this technique for training? And what are we learning about the mystery that is hypertrophy from studying the phenomena of occlusion for hypertrohhy strength?

These questions are addressed in an excellent review of occlusion research from 2008 called " Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise?"

Two of the highlights of the paper (at least for me) -the review of hypertrophy models such as they are and a possible rationale for the Pump in bodybuilding circles.

Overview on the (un)Known of Muscle Building

The authors go through an amazing job of investigating the known models of hypertrophy - and all that we dont know about it - to see where occlusion training may fit in with existing models. Heck, in order to understand what role occlusion plays, we need to have some sense of the depth and breadth of the puddle it's playing in.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Not just hormones, the reviewers look at other factors too - like mechano checmical. THat means that maybe the calcium involved in the actin/myosin bridge that enables contractions is a key to what's really important for hypertrophy - but so far there aren't studies looking at these responses in occlusion, so we have no comparison.

This review is great for myth busting. In other words, its review of what we can actually point to and say "that's what casues muscle growth" shows us what we know is so small, it's really exciting. Why is being able to say "but we don't know if that's what's doing it" exciting? One, it means we're starting to know what's going on in more detail to be able to say we don't know and two, it means in any discussion about somebody saying this is WHY this works (like why the pump "works") we can be pretty confident in knowing they maybe shouldn't be so confident.

It may seem a fine point, but work like this also lets us continue to say that "if you do this protocol, you'll get big" - assuming it's been tested on lots of athletes of various types. What we cannot say with the same confidence is WHY if we follow that protocol we're getting big.

I recommend the full first half of the article just for this review of the state of the art (as of 2008) on hypertrophy.

SO where does this get us then with occlusion and hypertrophy?

First a few words about occlusion training - what is it?

Occlusion training goes by a bunch of names: kaatsu training, occlusion, Blood Flow Restriction (BFR), ishemic training. Occlusion generally means to obstruct or block or even hide something (from view). In the case of muscle work, the blood flow is obstructed, usually by a tournequette of some kind. Ischemia is sort of the technical term for blood flow restriction - to the heart or other body tissue -as a result of some type of block (or occlusion).

Protocols - often seem to involve tournequetting the working limb, then using loads of 10-30% of a 1RM, usually lots of reps, very low rest, until fatigue hits. The results in strength gains are similar to working sets with 80% 1RMs.

The main benefit has been seen in rehab, getting a person who's too weak to work at heavy levels, back on their feet again. There's even been consideration of the use of this kind of training for astraunauts who, following Woolfs' and Davis's law do tend to lose it from not using it - their muscle that is.

So, we can start to see with results like this, it would be interesting to understand how low loads with a cuff can cause strength gains equivalent to 80% of a 1RM

Is It Safe?

One of the biggie first questions people have about occlusion is (well, what was yours>) - is - is it safe? The authors respond that by saying they looked at 13 studies with thousands of trials - and even in the one where the forearm was completely occluded for 20mins, there were no measurable ill effects.

Most sessions last only 5-10 mins, and are not full, but partial occlusion.

Likewise, i was reading a 2010 study that wanted to see if thrombosis symptoms would occur in healthy participants - another concern about occlusion - and nothing close to that effect was measured. So from these typical kinds of fears, no such effects it seems have been measured.

The one side effect "acute muscle pain" - i think this means similar to the burn sensation some folks get when going too far in a set. That's common with the "to fatigue" type training used in occlusion. DOMS is also common in the first few bouts. The authors suggest that with these cautions in mind "training combined with ischemia clearly requires a high degree of motivation from the trainee, especially if performed with a high level of effort."

Will that be Wide or Narrow?

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

Last year i looked at a study that just tied up the lower limbs with wide wraps. Important to note that the cuffs these folks are describing in the research reviews can have the pressure adjusted with the cuff to exact mmHg, similar to a blood pressure cuff.

I make no recommendations about whether it's better to use a proper occlusion cuff or just wrap up a limb; i only note that the places in Japan that have the most experience with this approach use Katsu cuffs - cuffs that enable control of pressure.

Is a Tournequette Even Necessary?

This is my favorite part of the paper because i think there's a link between what is described here, and what is discussed with the Pump (b2d overview here). See what you think.

First the authors point out that studies show the effect of an occlusion cuff is erased once loads get up to 40-60% load. What's interesting is that work using research's favorite - the leg extension - showed that even without a cuff, loads as low as 20% could induce "ischemic pain" - like that's a good thing.

The authors hypothesize that there are ways to get a low load ischemic effect without a cuff by doing the following: partials

So this is where my Pump query comes in: the Pump - if one is not overtraining and under nourished - is easy to achieve by using lots of reps with light loads, until one's arms or related feel like they're so full of blood they can't move. Sounds like kaatsu work.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.

What i'm intrigued by is that there seems to be a lot of circumstantial evidence to say that ishemia induced with low loads develops hypertrophy - but if anyone tries to say "and here's why that is" - and they start talking about NO supplements and flushing and who knows what all - you can pretty confidently say, well, based on what research?

In other words, there's a relationship it looks like, but what the actual mechanism is, we don't entirely know. Mybe it's fatiguing out type one and bringing on type II, maybe its IGF-1 goes up and myostatin goes down. Maybe it's mTOR levels. They're all in the soup. But what's cause and what's conincidence - ain't clear. But i sure as heck ain't gonna say the pump is a myth - just the explanations for it so far are pretty mythical.

To Cuff or Not to Cuff

One might think that just going for this kind of non-cuff'd based ischemia (blood pooling; can't flow back) is better than cuff based. Here's what the authors think:

What about the Dose?

To summarise a great long section of this paper, the results are not in for normal training about what the optimal frequence, volume, intensity is for optimal hypertrophic effect using occlusion.

The authors make a great note that not all ischemic training results in strength gains. For some reason, cycling isn't great for occlusion and strength development. On the other hand walk training is one of the big successes of occlusion work, and of course stength training - the short bursts of activity - is where the biggest benefit seems to be. Whether therefore the ratio between ischemia and reperfusion is key here, we just don't know but it seems to be a factor.

Will it Blend

So if we're not rehabbing, and with all the unknowns about dose, is it appropriate to put occlusion training into the mix of a regular strength program with "heavy" resistance.

I dunno.

The authors focus on work that's looked at two great benefits of heavy resistance training: bone mineral density and tendon stiffness.

In both cases lighter load work has been shown to have less of an effect on these factors. So - for ones bones, heavy resistance is a bonus - but then, so is stop and start action. For tendons, however, it seems that volume is also a key factor in enhancing stiffness (MTC descibed here - doesn't mean anything about flexibility, but about load, really)

In other words, while occlusion may not bring on the benefits of heavy resistance, there are other ways than heavy work to enhance these benefits so playing with ischemia may be useful for strength development.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome.  Trainer par excellance Roland Fisher introduced me to the timed sets of Huge in a Hurry

Trainer par excellance Roland Fisher introduced me to the timed sets of Huge in a Hurry 's Chad Waterbury. Very simple: get a weight at the end of a session where you can do 20 reps, and as soon as the fast tempo drops to complete the set, drop the weight, go for another 20. By using time as the marker, there's no way to get to fatigue and form failure. One heck of a pump, too. Thus, one has done their heavy work, and uses the occlusion level sets for a finisher. I love it. Your mileage may vary. See what you find.

's Chad Waterbury. Very simple: get a weight at the end of a session where you can do 20 reps, and as soon as the fast tempo drops to complete the set, drop the weight, go for another 20. By using time as the marker, there's no way to get to fatigue and form failure. One heck of a pump, too. Thus, one has done their heavy work, and uses the occlusion level sets for a finisher. I love it. Your mileage may vary. See what you find.

Wrap UP - sans wraps even

And speaking of finisher, the authors wrap up with the following. The first sentence for me is key:

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too.

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too.

The point is, i guess, that as this article started, just when we think we know something who'd a thought that strength can be aided by counter-intuitive actions like restricting blood supply? where does that map to evolution?

If nothing else, occlusion work shows us that we are complex systems with more than one path to create an effect.

Related Resources

Citations:

These questions are addressed in an excellent review of occlusion research from 2008 called " Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise?"

Two of the highlights of the paper (at least for me) -the review of hypertrophy models such as they are and a possible rationale for the Pump in bodybuilding circles.

Overview on the (un)Known of Muscle Building

The authors go through an amazing job of investigating the known models of hypertrophy - and all that we dont know about it - to see where occlusion training may fit in with existing models. Heck, in order to understand what role occlusion plays, we need to have some sense of the depth and breadth of the puddle it's playing in.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all.

Unaccustomed as i am to being brief, i'm actually not going to go through these models in detail here. Suffice it to say though that what we have often thought of as the biggie thing to boost in order to super charge hypertrophy may not hold. The authors do a lovely job of showing for instance that heh, post occlusion training, yes Growth Hormone (GH) is up and IGF-1 is up, but according to all this other research, we really don't know if the presence of these hormone levels is really what's upping protein synthesis at all. Not just hormones, the reviewers look at other factors too - like mechano checmical. THat means that maybe the calcium involved in the actin/myosin bridge that enables contractions is a key to what's really important for hypertrophy - but so far there aren't studies looking at these responses in occlusion, so we have no comparison.

This review is great for myth busting. In other words, its review of what we can actually point to and say "that's what casues muscle growth" shows us what we know is so small, it's really exciting. Why is being able to say "but we don't know if that's what's doing it" exciting? One, it means we're starting to know what's going on in more detail to be able to say we don't know and two, it means in any discussion about somebody saying this is WHY this works (like why the pump "works") we can be pretty confident in knowing they maybe shouldn't be so confident.

It may seem a fine point, but work like this also lets us continue to say that "if you do this protocol, you'll get big" - assuming it's been tested on lots of athletes of various types. What we cannot say with the same confidence is WHY if we follow that protocol we're getting big.

I recommend the full first half of the article just for this review of the state of the art (as of 2008) on hypertrophy.

SO where does this get us then with occlusion and hypertrophy?

First a few words about occlusion training - what is it?

Occlusion training goes by a bunch of names: kaatsu training, occlusion, Blood Flow Restriction (BFR), ishemic training. Occlusion generally means to obstruct or block or even hide something (from view). In the case of muscle work, the blood flow is obstructed, usually by a tournequette of some kind. Ischemia is sort of the technical term for blood flow restriction - to the heart or other body tissue -as a result of some type of block (or occlusion).

Protocols - often seem to involve tournequetting the working limb, then using loads of 10-30% of a 1RM, usually lots of reps, very low rest, until fatigue hits. The results in strength gains are similar to working sets with 80% 1RMs.

The main benefit has been seen in rehab, getting a person who's too weak to work at heavy levels, back on their feet again. There's even been consideration of the use of this kind of training for astraunauts who, following Woolfs' and Davis's law do tend to lose it from not using it - their muscle that is.

So, we can start to see with results like this, it would be interesting to understand how low loads with a cuff can cause strength gains equivalent to 80% of a 1RM

Is It Safe?

One of the biggie first questions people have about occlusion is (well, what was yours>) - is - is it safe? The authors respond that by saying they looked at 13 studies with thousands of trials - and even in the one where the forearm was completely occluded for 20mins, there were no measurable ill effects.

Most sessions last only 5-10 mins, and are not full, but partial occlusion.

Likewise, i was reading a 2010 study that wanted to see if thrombosis symptoms would occur in healthy participants - another concern about occlusion - and nothing close to that effect was measured. So from these typical kinds of fears, no such effects it seems have been measured.

The one side effect "acute muscle pain" - i think this means similar to the burn sensation some folks get when going too far in a set. That's common with the "to fatigue" type training used in occlusion. DOMS is also common in the first few bouts. The authors suggest that with these cautions in mind "training combined with ischemia clearly requires a high degree of motivation from the trainee, especially if performed with a high level of effort."

Will that be Wide or Narrow?

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.

The consensus is it seems that wide cuffs have the advantage: lower pressures can be used with wider cuffs. Likewise there are fewer shear force issues with wider cuff and one can stay away from complete occlusion with more control.Last year i looked at a study that just tied up the lower limbs with wide wraps. Important to note that the cuffs these folks are describing in the research reviews can have the pressure adjusted with the cuff to exact mmHg, similar to a blood pressure cuff.

I make no recommendations about whether it's better to use a proper occlusion cuff or just wrap up a limb; i only note that the places in Japan that have the most experience with this approach use Katsu cuffs - cuffs that enable control of pressure.

Is a Tournequette Even Necessary?

This is my favorite part of the paper because i think there's a link between what is described here, and what is discussed with the Pump (b2d overview here). See what you think.

First the authors point out that studies show the effect of an occlusion cuff is erased once loads get up to 40-60% load. What's interesting is that work using research's favorite - the leg extension - showed that even without a cuff, loads as low as 20% could induce "ischemic pain" - like that's a good thing.

The authors hypothesize that there are ways to get a low load ischemic effect without a cuff by doing the following: partials

Other quadriceps exercises can also be modified to achieve intramuscular restriction of blood flow. During closed kinetic chain exercises such as the squat and the leg press, the force demands of the movement dictate that the electrical activity of the quadriceps is high at flexed knee angles (90°–100°) and low near full-knee extension (Andersen et al., 2006). If the range of motion instead is limited to between ∼50° and 100° of flexion, the muscle activity remains fairly high throughout the movement and intramuscular occlusion is thus more likely to occur.The goal of going for ischemia with low loads is to get the benefit of heavier loads without having to use heavier loads that perhaps could not be taken to the given rep level.

So this is where my Pump query comes in: the Pump - if one is not overtraining and under nourished - is easy to achieve by using lots of reps with light loads, until one's arms or related feel like they're so full of blood they can't move. Sounds like kaatsu work.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes.

Now there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not the Pump really leads to hypertrophy. Some of the vigerous come backs are "i never train for the pump and i still get big" - while true not really a defence. And actually, what hasn't been directly tested it seems is post ishemia self-induced, does hypertrophy occur? A lot of body builders will say yes. What i'm intrigued by is that there seems to be a lot of circumstantial evidence to say that ishemia induced with low loads develops hypertrophy - but if anyone tries to say "and here's why that is" - and they start talking about NO supplements and flushing and who knows what all - you can pretty confidently say, well, based on what research?

In other words, there's a relationship it looks like, but what the actual mechanism is, we don't entirely know. Mybe it's fatiguing out type one and bringing on type II, maybe its IGF-1 goes up and myostatin goes down. Maybe it's mTOR levels. They're all in the soup. But what's cause and what's conincidence - ain't clear. But i sure as heck ain't gonna say the pump is a myth - just the explanations for it so far are pretty mythical.

To Cuff or Not to Cuff

One might think that just going for this kind of non-cuff'd based ischemia (blood pooling; can't flow back) is better than cuff based. Here's what the authors think:

Intuitively, a training model which is based on the muscles own internal restriction of blood flow would have advantages both from a safety point of view and from a practical point of view. On the other hand, in certain muscle groups and in some individuals, it may be difficult to induce relative ischemia at low loads by exercise alone, due to factors such as insufficient intramuscular pressures developed during exercise. Furthermore, it is possible that there are differences between the muscle ischemia resulting from exercise alone and the ischemia induced with a tourniquet in combination with exercise (e.g., a greater build-up of metabolites in the cuff-occluded muscle), which in turn could lead to differences in the stimulation of hypertrophic pathways. Future studies should compare the effects of ischemic training with and without cuff occlusion at the same level of effort.Another great "we don't know" but a great question: is cuffing the same kind of physiological response as non-cuffing occlusion effect?

What about the Dose?

To summarise a great long section of this paper, the results are not in for normal training about what the optimal frequence, volume, intensity is for optimal hypertrophic effect using occlusion.

The authors make a great note that not all ischemic training results in strength gains. For some reason, cycling isn't great for occlusion and strength development. On the other hand walk training is one of the big successes of occlusion work, and of course stength training - the short bursts of activity - is where the biggest benefit seems to be. Whether therefore the ratio between ischemia and reperfusion is key here, we just don't know but it seems to be a factor.

Will it Blend

So if we're not rehabbing, and with all the unknowns about dose, is it appropriate to put occlusion training into the mix of a regular strength program with "heavy" resistance.

I dunno.

The authors focus on work that's looked at two great benefits of heavy resistance training: bone mineral density and tendon stiffness.

In both cases lighter load work has been shown to have less of an effect on these factors. So - for ones bones, heavy resistance is a bonus - but then, so is stop and start action. For tendons, however, it seems that volume is also a key factor in enhancing stiffness (MTC descibed here - doesn't mean anything about flexibility, but about load, really)

In other words, while occlusion may not bring on the benefits of heavy resistance, there are other ways than heavy work to enhance these benefits so playing with ischemia may be useful for strength development.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome.

High Volume towards Ischemia? Again, to take another page from bodybuilding and powerlifting practice, mechanisms to increase volume without killing form or inducing failure can be awesome. Wrap UP - sans wraps even

And speaking of finisher, the authors wrap up with the following. The first sentence for me is key:

By seeing an interesting strength effect from occlusion, that raises the question how is this working in terms of what we know about hypertrophy? Turns out that in asking what we know about hypertrophy, it's surprisingly still very little. Lots about what's happening in the soup with strength training, but not lots of clear A therefore B. Having occlusion in the mix gives us a great point of comparison to be able to say at least what's different with the following factors (or the same) when blood flow is restricted? what's going on that this is happening? That's cool.

The research on resistance exercise performed during ischemic conditions has so far provided important new insights into the physiology of strength training. In addition to being a possible alternative or complement to conventional high-load resistance training in certain situations, ischemic strength training may also have a place in sports training. Because relative ischemia can be induced at rather low loads in certain exercises even without tourniquets, external pressure may not always be necessary to achieve significant training effects. Also, any unique effects of cuff occlusion per se during exercise have yet to be determined because the increased training effects observed in the studies published to date may simply have been due to greater effort. With reference to training combined with cuff occlusion, current evidence suggests that this mode of exercise is relatively safe, but more research is needed especially regarding the potential adverse effects on soft tissues.

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too.

Meanwhile, if you wish to try occlusion training yourself, there's only about 4 uni's in the US using it; most work is in Japan. Here's an intereting PDF that talks about a specific Kaatsu cuff system, too. The point is, i guess, that as this article started, just when we think we know something who'd a thought that strength can be aided by counter-intuitive actions like restricting blood supply? where does that map to evolution?

If nothing else, occlusion work shows us that we are complex systems with more than one path to create an effect.

Related Resources

- Occlusion Training

- Get Huge or Die

- Protein Ingestion and Protein Sythesis

- Nutrient Timing for muscle building

- Creatine and Beta Alanine

- Does this stuff work?

- the Pump

Citations:

Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Wernbom M, Augustsson J, & Raastad T (2008). Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 18 (4), 401-16 PMID: 18466185

Madarame, H., Kurano, M., Takano, H., Iida, H., Sato, Y., Ohshima, H., Abe, T., Ishii, N., Morita, T., & Nakajima, T. (2010). Effects of low-intensity resistance exercise with blood flow restriction on coagulation system in healthy subjects Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 30 (3), 210-213 DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00927.x

Loenneke, J., & Pujol, T. (2009). The Use of Occlusion Training to Produce Muscle Hypertrophy Strength and Conditioning Journal, 31 (3), 77-84 DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181a5a352

Labels:

muscle,

occlusion,

occlusion training,

strength,

strength training

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Hypoxia for Muscle Growth: Get Huge or Die?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

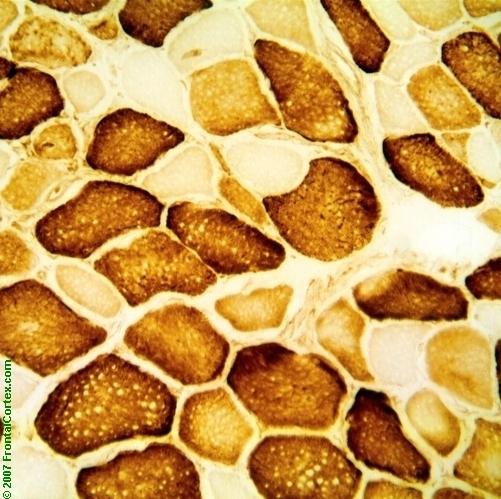

A recently accepted paper shows that working in an oxygen deprived environment can gosh darn it, build muscle when doing resistance work. WHile jokes might start about the variety of ways that one could replicate a near-asphyxiated space - from smoking to putting a plastic bag (with some holes) over one's head - i'm thinking that in the case of resistance training (as opposed to altitude/endurance where there's a definite blood/muscle adaptation), based on the findings, we're maybe seeing predictably heightened threat response brought on by 02 deprivation. Here's a look at the study in detail:

A recently accepted paper shows that working in an oxygen deprived environment can gosh darn it, build muscle when doing resistance work. WHile jokes might start about the variety of ways that one could replicate a near-asphyxiated space - from smoking to putting a plastic bag (with some holes) over one's head - i'm thinking that in the case of resistance training (as opposed to altitude/endurance where there's a definite blood/muscle adaptation), based on the findings, we're maybe seeing predictably heightened threat response brought on by 02 deprivation. Here's a look at the study in detail:

What is it with Japanese research and oxygen deprivation? They bring us the most amazing results of occlusion training (b2d discussion here). Now, how about whole body oxygen occlusion?

Some may argue that this seems to be similar to training at altitude, where the benefits are known. Indeed, the authors use a system that's used to generate Everest-like conditions, funnily enough called an "everest generator" and for 5K you can have one, too (shown left).

Some may argue that this seems to be similar to training at altitude, where the benefits are known. Indeed, the authors use a system that's used to generate Everest-like conditions, funnily enough called an "everest generator" and for 5K you can have one, too (shown left).

Thing is, this technique is most often used for endurance athletes (and we've also seen in cycling for instance blood doping associated cases of EPO enriched/adapted blood), and apparently the usual oxygen depletion levels are 20.9% o2 - with associated increased risks of overtraining. Here, in this resistance training study, the researchers use 13ish% o2.

Another unique aspect of this hypoxia study is it's the first time (to my knowledge anyway) researchers have formally looked at effects on resistance training - anaerobic effort as opposed to aerobic effort.

The Rationale: it IS occlusion training. The authors do indeed say yup well, LOW INTENSITY resistance training and partial occlusion has great effect, so how about "systemic hypoxia" - It's the next logical step, isn't it?

Set Up. 10 reps of bench and squat at 70% of tested 1RM in either normal room air or 13% O2. I'm only able to guess that 13% is some standard definition of "acute hypoxia" conditions that are still safe.

The authors alas don't formally justify either why they were going for this percentage or why this definitely NOT low resistance level (like occlusion training uses) was used.

All sorts of Measures. The purpose of the trials were so the researchers will have

And what all the lads love to hear: serum GH - significantly higher in the hypoxia case (potentially triggered, the researchers suppose by increased catecholamine release) Likewise IGF and of course yes the big T, testosterone. But so does cortisol.

And for those trying to burn fat? Not surprisingly to folks who see the world through the nervous system threat/no threat lense, those wonderful fight or flight catecholamines are of course elevated, too. These are the things that help fat mobilisation (discussed here in this b2d piece on HIIT). So gosh, let's see - challenge trying to breath - i'd say that's going to be perceived as a threat to one's system?

So What's Different (than occlusion training)?

The authors suggest that while occlusion training has shown greater muscle growth, they haven't really known why. They put it down to the increased levels of GH noted in occlusion training at LOW REPS. Here they're saying

What they say their specific results also suggest is that IGF-1 may be indedpendent of GH levels. In other words, something else is going on to get a boost in IGF-1 than the presence of GH.

Likewise, they suggest that increases in serum testosterone may have more to do with intensity and muscle mass than "metabolic stress" - like hypoxia.

As for cortisol, another fight or flight hormone, that's also a known biproduct of resistance training. The researchers say they just don't know what the mechanism is such that these levels are particularly higher in this trial. Well heck, again, threat-related hormone; gonna asphixiate. Dunno. seems predictable when seen from that vantage?

Not Normal. The threat hormones did not return to normal levels within an hour after the trials either. Is that good? Not clear, but if overtraining is related to stressing they system, threatening it more than it can handle perhaps, then it's reasonable to see why this kind of training may need to be far more closely monitored for overtraining effects.

Openning New Doors. The biggest outcome it seems right now is the possible relationship of hypoxia to GH - at least in the authors' view:

hypoxic environment in anaerobic work like resistance training - hence the term anaerobic - so it's interesting to see therefore that the hypoxic effect seems to be perhaps on the recovery - where we usually pause between sets to catch our breath and re-oxygenate. Here, in this o2 deprived envrionment, that can't happen. Hence lactate it seems to me goes up. And GH switches in.

hypoxic environment in anaerobic work like resistance training - hence the term anaerobic - so it's interesting to see therefore that the hypoxic effect seems to be perhaps on the recovery - where we usually pause between sets to catch our breath and re-oxygenate. Here, in this o2 deprived envrionment, that can't happen. Hence lactate it seems to me goes up. And GH switches in.

Why, when the nervous system might be percieved to be under threat, would the nervous system/brain see this as a good time to, er, grow? (For a review of the systems that get shut down under stress, see this overview of Zebras and Baboons and Stress.)

Again, what these researchers don't seem to clue into is that growth hormone is apparently known to be triggered by stress (and here's a pdf from 76 about how kind of cool this is, where only 1/3 of the sample group was shown to have this particular stress/GH release response). It's role this work shows, is not just to grow the body, but the brain. Is that what's going on? I'm about to die; i suddenly need a bigger brain?

Ramdoc, over at the dragondoor forum (thank you), made the intriguing connexion that GH is related to insulin. Here's 2005 paper outlining the human GH/insulin homeostasis, and that bigger hits of GH lead to a hyperinsulinism - elevated levels of insulin in the bloodstream. That's gonna trigger a temporary blood glucose surge. So if increased GH relates to a rush of glucose to the bloodstream, that certainly would have a survival effect. More fast energy, that means more ATP, more muscle can be recruited, more speed, steve. Cool.

We're about to Die; Let's get Huge?

Well who'd have thought even to test the effects of cutting off c irculation to see what would happen to our bodies?

irculation to see what would happen to our bodies?

I suppose it's an interesting idea - take a process like anaerobic metabolism and string it out to see if by seeing what happens in a less natural environment, we get some better view into a natural environment. And heck, some folks might turn that practice into a way to rehab and train folks.

The responses seen in this environment - a big fat rush of fight or flight related responses - seem pretty predictable. That there's a positive payoff FROM that stress after the event is interesting: survive and get faster, stronger. Recovery means anabolism: more muscle, continued performance improvement. And who knows? Maybe a bigger smarter brain?

But in terms of pushing this principle that's being expressed in the large in this oxygen deprived space? The biggie that those stress levels don't go back to normal in normal time is a reminder that hypoxia work may just be super stressful to our CNS even if we mayn't perceive that directly ourselve - and this study doesn't tell us if it collected any of the athletes' responses to the protocol.

In the meantime, for those who are curious, how would one try this at home without an Hypoxia Generator? The mind reels at the possibilities.

Related Posts

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

Effects of Acute Hypoxia on Metabolic and Hormonal Responses to Resistance Exercise.

Kon M, Ikeda T, Homma T, Akimoto T, Suzuki Y, Kawahara T.

1Department of Sports Sciences, Japan Institute of Sports Sciences, 3-15-1 Nishigaoka, Kita, Tokyo, 115-0056, Japan; 2Laboratory of Regenerative Medical Engineering, Center for Disease Biology and Integrative Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan.

INTRODUCTION:: Several recent studies have shown that resistance exercise combined with vascular occlusion effectively causes increases in muscular size and strength. Researchers speculated that the vascular occlusion-induced local hypoxia may contribute to the adaptations via promoting anabolic hormone secretions stimulated by local accumulation of metabolic subproducts. Here we examined whether acute systemic hypoxia affects metabolic and hormonal responses to resistance exercise. METHODS:: Twelve male subjects participated in two experimental trials: 1) resistance exercise while breathing normoxic air [normoxic resistance exercise (NR)], 2) resistance exercise while breathing 13 % oxygen [hypoxic resistance exercise (HR)]. The resistance exercises (bench-press and leg-press) consisted of 10 repetitions for five sets at 70 % of maximum strength with 1-min rest between sets. Blood lactate, serum growth hormone (GH), epinephrine (E), norepinephrine (NE), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), testosterone, and cortisol concentrations were measured before normoxia and hypoxia exposures, 15-min after the exposures, and at 0, 15, 30, 60 min after the exercises. RESULTS:: Lactate significantly increased after exercises in both trials (p < style="color: rgb(153, 51, 0);">These findings suggest that resistance exercise in hypoxic condition caused greater accumulation of metabolites, and strong anabolic hormone response.

What is it with Japanese research and oxygen deprivation? They bring us the most amazing results of occlusion training (b2d discussion here). Now, how about whole body oxygen occlusion?

Some may argue that this seems to be similar to training at altitude, where the benefits are known. Indeed, the authors use a system that's used to generate Everest-like conditions, funnily enough called an "everest generator" and for 5K you can have one, too (shown left).

Some may argue that this seems to be similar to training at altitude, where the benefits are known. Indeed, the authors use a system that's used to generate Everest-like conditions, funnily enough called an "everest generator" and for 5K you can have one, too (shown left).Thing is, this technique is most often used for endurance athletes (and we've also seen in cycling for instance blood doping associated cases of EPO enriched/adapted blood), and apparently the usual oxygen depletion levels are 20.9% o2 - with associated increased risks of overtraining. Here, in this resistance training study, the researchers use 13ish% o2.

Another unique aspect of this hypoxia study is it's the first time (to my knowledge anyway) researchers have formally looked at effects on resistance training - anaerobic effort as opposed to aerobic effort.

The Rationale: it IS occlusion training. The authors do indeed say yup well, LOW INTENSITY resistance training and partial occlusion has great effect, so how about "systemic hypoxia" - It's the next logical step, isn't it?

Set Up. 10 reps of bench and squat at 70% of tested 1RM in either normal room air or 13% O2. I'm only able to guess that 13% is some standard definition of "acute hypoxia" conditions that are still safe.

The authors alas don't formally justify either why they were going for this percentage or why this definitely NOT low resistance level (like occlusion training uses) was used.

All sorts of Measures. The purpose of the trials were so the researchers will have

examined the effects of resistance exercise on metabolic and hormonal responses under acute systemic hypoxia. We hypothesized that the resistance exercise in hypoxic condition would cause greater accumulation of metabolic subproducts, and greater responses of anabolic hormones.To this end, a lot of measures were taken of muscle oxidation, hormones, fuel produced (like lactate). As the abstract says, blood lactate levels were significantly higher in the hypoxia trial than in the normal air trial. This isn't much of a surprise, given that lactate tends to kick in as it gets harder for the body to oxidize fuel in the mitochondria. A goal of Vo2max training (like viking warrior conditioning, reviewed here) is to increase the lactate threshold - the level of effort and time before which bi products of lactate production (H+ ions) can no longer be buffered out of the blood.

And what all the lads love to hear: serum GH - significantly higher in the hypoxia case (potentially triggered, the researchers suppose by increased catecholamine release) Likewise IGF and of course yes the big T, testosterone. But so does cortisol.

And for those trying to burn fat? Not surprisingly to folks who see the world through the nervous system threat/no threat lense, those wonderful fight or flight catecholamines are of course elevated, too. These are the things that help fat mobilisation (discussed here in this b2d piece on HIIT). So gosh, let's see - challenge trying to breath - i'd say that's going to be perceived as a threat to one's system?

So What's Different (than occlusion training)?

The authors suggest that while occlusion training has shown greater muscle growth, they haven't really known why. They put it down to the increased levels of GH noted in occlusion training at LOW REPS. Here they're saying

In the present study, we revealed that systemic hypoxia was actually associated with greater GH response to resistance exercise for the first time. The hypoxia may play a key role in the low intensity resistance training with vascularInteresting that systemic hypoxia is being used to understand the mechanisms of a more local phenomena like Kaatsu cuffing.

occlusion-induced muscular hypertrophy

What they say their specific results also suggest is that IGF-1 may be indedpendent of GH levels. In other words, something else is going on to get a boost in IGF-1 than the presence of GH.

Likewise, they suggest that increases in serum testosterone may have more to do with intensity and muscle mass than "metabolic stress" - like hypoxia.

As for cortisol, another fight or flight hormone, that's also a known biproduct of resistance training. The researchers say they just don't know what the mechanism is such that these levels are particularly higher in this trial. Well heck, again, threat-related hormone; gonna asphixiate. Dunno. seems predictable when seen from that vantage?

Not Normal. The threat hormones did not return to normal levels within an hour after the trials either. Is that good? Not clear, but if overtraining is related to stressing they system, threatening it more than it can handle perhaps, then it's reasonable to see why this kind of training may need to be far more closely monitored for overtraining effects.

Openning New Doors. The biggest outcome it seems right now is the possible relationship of hypoxia to GH - at least in the authors' view:

... it is necessary to investigate whether hypoxic exposure plays an important role for the expressions of genes involving muscular hypertrophy in the future...Our data suggest that hypoxia is a potent factor for the enhancements of anabolic hormone (GH) response to resistanceWhy when fleeing the Tiger does GH turn on? Intriguingly, we already induce a kind of

hypoxic environment in anaerobic work like resistance training - hence the term anaerobic - so it's interesting to see therefore that the hypoxic effect seems to be perhaps on the recovery - where we usually pause between sets to catch our breath and re-oxygenate. Here, in this o2 deprived envrionment, that can't happen. Hence lactate it seems to me goes up. And GH switches in.

hypoxic environment in anaerobic work like resistance training - hence the term anaerobic - so it's interesting to see therefore that the hypoxic effect seems to be perhaps on the recovery - where we usually pause between sets to catch our breath and re-oxygenate. Here, in this o2 deprived envrionment, that can't happen. Hence lactate it seems to me goes up. And GH switches in.Why, when the nervous system might be percieved to be under threat, would the nervous system/brain see this as a good time to, er, grow? (For a review of the systems that get shut down under stress, see this overview of Zebras and Baboons and Stress.)

Again, what these researchers don't seem to clue into is that growth hormone is apparently known to be triggered by stress (and here's a pdf from 76 about how kind of cool this is, where only 1/3 of the sample group was shown to have this particular stress/GH release response). It's role this work shows, is not just to grow the body, but the brain. Is that what's going on? I'm about to die; i suddenly need a bigger brain?

Ramdoc, over at the dragondoor forum (thank you), made the intriguing connexion that GH is related to insulin. Here's 2005 paper outlining the human GH/insulin homeostasis, and that bigger hits of GH lead to a hyperinsulinism - elevated levels of insulin in the bloodstream. That's gonna trigger a temporary blood glucose surge. So if increased GH relates to a rush of glucose to the bloodstream, that certainly would have a survival effect. More fast energy, that means more ATP, more muscle can be recruited, more speed, steve. Cool.

We're about to Die; Let's get Huge?

Well who'd have thought even to test the effects of cutting off c

irculation to see what would happen to our bodies?

irculation to see what would happen to our bodies?I suppose it's an interesting idea - take a process like anaerobic metabolism and string it out to see if by seeing what happens in a less natural environment, we get some better view into a natural environment. And heck, some folks might turn that practice into a way to rehab and train folks.

The responses seen in this environment - a big fat rush of fight or flight related responses - seem pretty predictable. That there's a positive payoff FROM that stress after the event is interesting: survive and get faster, stronger. Recovery means anabolism: more muscle, continued performance improvement. And who knows? Maybe a bigger smarter brain?

But in terms of pushing this principle that's being expressed in the large in this oxygen deprived space? The biggie that those stress levels don't go back to normal in normal time is a reminder that hypoxia work may just be super stressful to our CNS even if we mayn't perceive that directly ourselve - and this study doesn't tell us if it collected any of the athletes' responses to the protocol.

In the meantime, for those who are curious, how would one try this at home without an Hypoxia Generator? The mind reels at the possibilities.

Related Posts

- Threat response - movement

- Catecholamines release in HIIT

Labels:

adaptation,

fitness,

hypertrophy,

muscle growth,

strength training,

wellbeing

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

COACHING with dr. m.c.

COACHING with dr. m.c.