Showing posts with label integrating strength and cardio. Show all posts

Showing posts with label integrating strength and cardio. Show all posts

Saturday, October 17, 2009

The Pump: What is it, Does it Work and if so How and for What Kind of Muscle Growth?

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

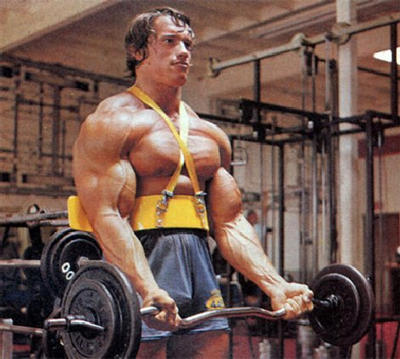

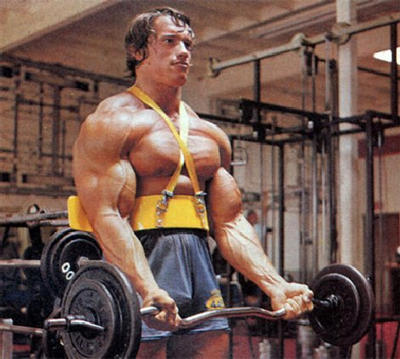

Ahnold reportedly loved "the pump" but what is the "pump" really in terms of muscle building? While it's easy to explain both what happens in

Ahnold reportedly loved "the pump" but what is the "pump" really in terms of muscle building? While it's easy to explain both what happens in  generating a pump, and how to create a pump - it's delightfully easy - it's hard to find any evidence behind the incredible claims about why this effect is said to be "essential" to achieving growth.

generating a pump, and how to create a pump - it's delightfully easy - it's hard to find any evidence behind the incredible claims about why this effect is said to be "essential" to achieving growth.

What is the Pump and How Get One?

Generally speaking the pump is the feeling one gets when pushing more blood into the muscle faster than it will flow out, so for a short time, until it does flow back out to a normal level, the muscle is all "pumped" up, and feels HUGE. This is also where a lot of folks get into nitric oxide products in an effort to extend the effects of the pump. Intriguingly, nitric oxide in studies has only been shown to preserver muscle not help it grow. But that's an aside.

Getting a pump is fun. It's something i've been playing with on my arms after a hard strength workout. I drop the weight to the 12RM weight and do a couple of fast sets (perfect form of course), and then, i'll go to a 20RM for one or two sets of different curls and may only do partials to really get the sweet spot. Bi's one way; tri's the other. What fun! And whip out that measuring tape. Goodness, isn't that remarkable! Strike the pose and take the picture, you bet.

Lack of Pump = Fatigue?

Now all the above does sound easy, but apparently there are times when the pump doesn't seem to be happening. Lonnie Lowery talks about this and suggests, beyond a few high rep 20 sets, making sure the potassium levels are good, and that you're warm not cold (easier vasodilation perhaps) is a good thing. Back off periods and basic carb availability are all good too. Carbs afterall help hold fluid. In fact Lowery has a whole diet here.

Interestingly, Lowery's not making any claims it seems about whether the pump actually helps muscle building or not; he's just saying it's a really nice motivating thing to have: to be able to get HUGE. What's more interesting is Lowery's correlation to lack of getting a pump as a sign of fatigue. Hence his mainly recovery and dietary advice to get that pump back. interesting.

So is this wonderful feeling contributing to muscle growth?

Muscle Hypertrophy 101: the types of muscle hypertrophy

So let's back up a bit. What is muscle growth? We know that there are usually two kinds discussed: sarcoplasmic - the tissue/fluids surrounding muscle fibers - and myofibral - the fibers of the muscles themselves getting bigger due to myofibral growth around the fibers.

know that there are usually two kinds discussed: sarcoplasmic - the tissue/fluids surrounding muscle fibers - and myofibral - the fibers of the muscles themselves getting bigger due to myofibral growth around the fibers.

It has been argued that power type training privileges myofibril hypertrophy and "hypertrophy" strength training privileges sarcoplasmic - what some folks see as fake hypertrophy because it is non-strength aiding growth of the sarcoplasm of the muscle. This assessment may be a bit cruel. It's actually very hard to get one kind of growth without the other occurring as well. All i'm saying is that different types of strength training may privilege one form over the other, but both will occur. And a good thing too. Myofibral growth demands some adaptation of the sarcomers to support them, too.

Ok, in either case, to the best of our knowledge (because there's a LOT we don't know about hypertrophy) what causes muscles to grow? Forcing them to respond to new demands. If there's no need to adapt do they adapt? well, no. And this is why if one does the same routine forever, the body doesn't change. Folks talk about plateaus. So, we usually use load or volume or a combination of both to create the conditions for adaptation.

And this is why if one does the same routine forever, the body doesn't change. Folks talk about plateaus. So, we usually use load or volume or a combination of both to create the conditions for adaptation.

Occlusion

Now interestingly, there is work on muscle growth (the strength kind) that has been shown to occur from something called occlusion training. This is where bloodflow is restricted around a limb, and far lighter weights are then used for reps. Intriguingly growth happens.

Ok, so now that we have some background on muscle growth, let's look at how The Pump has been described to help muscle growth

The Pump - per se.

Let's take a look at how the Pump is described to contribute to muscle growth first. An un-cited article on bodybuilding.com by "muscleTech" puts it this way:

Alas, no sources in the article to support these assertions.

Another theory of the pump expressed by Jeff Anderson is that the pump actually privileges slow twitch muscle fibers. That makes sense for two reasons: lots of low weight reps is moving into endurance world, which means oxidative capacity, aerobic energy rather than anaerobic capacity/ernergy. So Mr. Anderson says that by constantly pushing blood into these fibers, the fibers themseleves adapt to hold more blood. That means more capillaries in the fibers to help shunt the blood more effectively, and they're going to be rather densely packed as their numbers go up.

So you get the sense from this explanation that size noticed to hold more blood more of the time is going to make the muscle appear larger. Sarcoplasmic kind of growth?

Here's why i go more for Mr. Anderson's than MuscleTech's explanation. Our tissues are always adapting. If you squish more into them, they'll start to enlarge. So that's kinda funny - it's adding fluid (blood etc) into the muscle, but not increasing the number of myofibrils. So that doesn't sound like a strength gain; sounds more sarcoplasmic.

The Pump: can we get some science in here? Not easily.

The pump seems to work with two sides of something called hyperemia - active and reactive. The active one is caused by muscle contraction - do that a lot in exercise, eh? - which causes blood to congest in an area. Then there's reactive hyperemia - where blood that's supposed to get out is blocked - like there's a tourniquet causing yup, occlusion.

So, if there's occlusion, that means that blood is kinda stuck somewhere. That doesn't sound like blood is getting forced through to clear out "muscle toxins" or to induce the other popular concept of "muscle flushing" - sounds like it's getting stuck and stale.

If we look at "hyperemia" & "resistance training" in the science literature, we don't find stuff about muscle building. The kind of literature that's there is about the degree to which different kinds of training enhance the flow of blood or the dilation of the arteries. In other words, we generally apparently want to reduce reactive hyperemia.

Now while i've seen claims that moderate rep schemes are "are optimal to build muscle mass " because in part they "Enhances cellular hydration — greater muscle pump (called "reactive hyperemia") drives plasma and water to muscle which stimulates protein synthesis and inhibits proteolysis (protein breakdown)." i can't find any sources that explain that plasma and water driven to a muscle stimulates protein synthesis. We do know is that protein stimulates muscle synthesis. And we know that insulin stimulates protein synthesis and glucose stimulates protein synthesis. So maybe if there's all that stuff in plasma, yes we have protein synthesis stimulation. But that seems to happen whether we have high or low rep training. But again, is more more?

An Idea: the Pump Works Like Occlusion?

Mr. Anderson above proposes that the pump mainly effects slow twitch oxidative fibers because of capilarization (no strength; just mass). Dr. Lowery suggests that not being able to get a pump is a sign of fatigue - this i think is important. BUT if we look at occlusion training (which reactive hyperemia seems to be a type), then the pump should also be affecting both fast and slow twitch fibers' myofibral growth. Occlulusion, it seems, may indeed get fast twitch fibers involved more directly than without occlusion - that's a theory. Since we also see in low load occlusion training effects on strength: it goes up. SO is this kind of self-occlusion with self-selected low resistance weights to induce the effect having the same effect as a cuff? Could be - as per this review.

So, what about that pump?

Proposal 1: more is more: As far as i can tell, the suggestions are that it's supposed to help circulate good stuff in by vasodilateion, and then get the stale stuff out. Now for me - based on what i know - this seems the weakest case since we're not talking about steady blood flow in and out with the pump, but "reactive hyperemia" which means that blood is pumped in, and it can't get out again for a good half hour. There's no "flushing" if that's the case is there? Dave Barr talks about the "anabolic pump" - but again, i can't find this in the literature.

Proposal 2: bulking up with fluid. The other proposal that anderson suggests - and i'm not sure where he gets it from, but seems to make sense, is that pushing a lot of blood into the veins - especially of slow twitch fibers - is going to cause the fibers that hold the blood to adapt - get thicker, more and denser capillaries (the little gates that open for blood to flow in but not back out). SO that's just bulking up - what most folks talk about as sarcoplasmic type hypertrophy - but this seems even more particular as it's strictly related to blood volume taking up more room.

Proposal 3: occlusion causing real muscle fiber change - or not. What makes more sense to me is a combo of this adaptation of capillaries AND actual fiber change potentially caused by self-occlusion. BUT folks like Chad Waterbury, respected strength coach, are very skeptical of the pump and any correlation to muscle gain.

Maybe, Maybe Not, It depends

As said, there's a lot that remains unknown about the whys and hows of hypertrophy. The role of the pump seems to be just as really clearly ambiguous as to whether or not it aids hypertrophy or not.

I like the correlation Lowery seems to make implicitly between achieving the pump and fatigue. That seems useful.

For myself, right now, it's fun to play with a pump well after i've completed the hard work of the strength workouts i'm doing. Whether it's doing anything functional or not, i dunno, but since there seems *some* sense to it, i'm willing to give it a bit of a go - for now.

And so... The above is not meant as an exhaustive overview of all things to do with the pump - it's just what i could find by a couple day's digging. IF there are studies that you know of that support or study the pump with respect to muscle hypertrophy, please add a comment. Will be keen to hear.

I wonder too if a study that took the same kind of athletes and one did a regular routine and the other finished with pump sets and the other didn't if that would be conclusive or that one would just say - well they other group did a bit more volume. I suppose one could vary the loads or reps. But it would be interesting to see some kind of work.

Also, i do know that just because it hasn't been researched doesn't mean there's not an effect, but as per that first "explanation" of why the pump works - supposedly - for hypertrophy - if one is going to provide physiological rationales for an effect, please just point to the mechanisms that have been shown to result in these effects - it has to be sourced somewhere. And if not, well, the best we can say is that, in some cases, there seems to be a strong correlation between pumping and hypertrophy - either sarcoplasmic or myofibral - what that mechanism is - pretty much unknown at the moment.

Again - this is just the best i can do right now to make sense of this concept. If you have more information/sources, please share.

Thanks

Related Posts:

Citations:

Wernbom M, Augustsson J, & Raastad T (2008). Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 18 (4), 401-16 PMID: 18466185

Loenneke, J., & Pujol, T. (2009). The Use of Occlusion Training to Produce Muscle Hypertrophy Strength and Conditioning Journal, 31 (3), 77-84 DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181a5a352 Tweet Follow @begin2dig

generating a pump, and how to create a pump - it's delightfully easy - it's hard to find any evidence behind the incredible claims about why this effect is said to be "essential" to achieving growth.

generating a pump, and how to create a pump - it's delightfully easy - it's hard to find any evidence behind the incredible claims about why this effect is said to be "essential" to achieving growth.What is the Pump and How Get One?

Generally speaking the pump is the feeling one gets when pushing more blood into the muscle faster than it will flow out, so for a short time, until it does flow back out to a normal level, the muscle is all "pumped" up, and feels HUGE. This is also where a lot of folks get into nitric oxide products in an effort to extend the effects of the pump. Intriguingly, nitric oxide in studies has only been shown to preserver muscle not help it grow. But that's an aside.

Getting a pump is fun. It's something i've been playing with on my arms after a hard strength workout. I drop the weight to the 12RM weight and do a couple of fast sets (perfect form of course), and then, i'll go to a 20RM for one or two sets of different curls and may only do partials to really get the sweet spot. Bi's one way; tri's the other. What fun! And whip out that measuring tape. Goodness, isn't that remarkable! Strike the pose and take the picture, you bet.

Lack of Pump = Fatigue?

Now all the above does sound easy, but apparently there are times when the pump doesn't seem to be happening. Lonnie Lowery talks about this and suggests, beyond a few high rep 20 sets, making sure the potassium levels are good, and that you're warm not cold (easier vasodilation perhaps) is a good thing. Back off periods and basic carb availability are all good too. Carbs afterall help hold fluid. In fact Lowery has a whole diet here.

Interestingly, Lowery's not making any claims it seems about whether the pump actually helps muscle building or not; he's just saying it's a really nice motivating thing to have: to be able to get HUGE. What's more interesting is Lowery's correlation to lack of getting a pump as a sign of fatigue. Hence his mainly recovery and dietary advice to get that pump back. interesting.

So is this wonderful feeling contributing to muscle growth?

Muscle Hypertrophy 101: the types of muscle hypertrophy

So let's back up a bit. What is muscle growth? We

know that there are usually two kinds discussed: sarcoplasmic - the tissue/fluids surrounding muscle fibers - and myofibral - the fibers of the muscles themselves getting bigger due to myofibral growth around the fibers.

know that there are usually two kinds discussed: sarcoplasmic - the tissue/fluids surrounding muscle fibers - and myofibral - the fibers of the muscles themselves getting bigger due to myofibral growth around the fibers.It has been argued that power type training privileges myofibril hypertrophy and "hypertrophy" strength training privileges sarcoplasmic - what some folks see as fake hypertrophy because it is non-strength aiding growth of the sarcoplasm of the muscle. This assessment may be a bit cruel. It's actually very hard to get one kind of growth without the other occurring as well. All i'm saying is that different types of strength training may privilege one form over the other, but both will occur. And a good thing too. Myofibral growth demands some adaptation of the sarcomers to support them, too.

Ok, in either case, to the best of our knowledge (because there's a LOT we don't know about hypertrophy) what causes muscles to grow? Forcing them to respond to new demands. If there's no need to adapt do they adapt? well, no.

And this is why if one does the same routine forever, the body doesn't change. Folks talk about plateaus. So, we usually use load or volume or a combination of both to create the conditions for adaptation.

And this is why if one does the same routine forever, the body doesn't change. Folks talk about plateaus. So, we usually use load or volume or a combination of both to create the conditions for adaptation.Occlusion

Now interestingly, there is work on muscle growth (the strength kind) that has been shown to occur from something called occlusion training. This is where bloodflow is restricted around a limb, and far lighter weights are then used for reps. Intriguingly growth happens.

Ok, so now that we have some background on muscle growth, let's look at how The Pump has been described to help muscle growth

The Pump - per se.

Let's take a look at how the Pump is described to contribute to muscle growth first. An un-cited article on bodybuilding.com by "muscleTech" puts it this way:

The release of nitric oxide facilitates the relaxation of the endothelial cells — smooth muscles that line the blood vessels — thereby expanding the lumen of the blood vessel (the middle space of a blood vessel where blood flows through). As the lumen expands, blood flow is enhanced, resulting in peak vasodilation. Blood plasma is the primary channel through which nutrients, amino acids, testosterone, growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) are delivered to your starving muscles. Therefore, by feeding your system more blood, you transport elevated amounts of the various musclebuilding catalysts directly to your hard-working muscle cells.Wow. There's a lot going on in there. What it really seems to say is that more is better. Open a Bigger Pipe to let More Stuff through. Push through more blood with more protein, growth factor, testosterone all pushed into to muscles. That must be good right? Really? And even more fresh blood to push out "muscle toxins" would be great too, right? Hmm.

Another example of how the pump powers growth is through the role of oxygen. Increasing the delivery of oxygen-rich red blood cells to your starving muscles accelerates the speed at which your system is able to cleanse itself of muscle toxins such as ammonia.

Achieving maximum vasodilation also allows your body to quickly deliver metabolized amino acids and nutrients that are derived from your pre- and post-workout nutrition, and shuttle them directly to your hypertrophying muscles — allowing for enhanced muscle recovery and growth

Alas, no sources in the article to support these assertions.

Another theory of the pump expressed by Jeff Anderson is that the pump actually privileges slow twitch muscle fibers. That makes sense for two reasons: lots of low weight reps is moving into endurance world, which means oxidative capacity, aerobic energy rather than anaerobic capacity/ernergy. So Mr. Anderson says that by constantly pushing blood into these fibers, the fibers themseleves adapt to hold more blood. That means more capillaries in the fibers to help shunt the blood more effectively, and they're going to be rather densely packed as their numbers go up.

So you get the sense from this explanation that size noticed to hold more blood more of the time is going to make the muscle appear larger. Sarcoplasmic kind of growth?

Here's why i go more for Mr. Anderson's than MuscleTech's explanation. Our tissues are always adapting. If you squish more into them, they'll start to enlarge. So that's kinda funny - it's adding fluid (blood etc) into the muscle, but not increasing the number of myofibrils. So that doesn't sound like a strength gain; sounds more sarcoplasmic.

The Pump: can we get some science in here? Not easily.

The pump seems to work with two sides of something called hyperemia - active and reactive. The active one is caused by muscle contraction - do that a lot in exercise, eh? - which causes blood to congest in an area. Then there's reactive hyperemia - where blood that's supposed to get out is blocked - like there's a tourniquet causing yup, occlusion.

So, if there's occlusion, that means that blood is kinda stuck somewhere. That doesn't sound like blood is getting forced through to clear out "muscle toxins" or to induce the other popular concept of "muscle flushing" - sounds like it's getting stuck and stale.

If we look at "hyperemia" & "resistance training" in the science literature, we don't find stuff about muscle building. The kind of literature that's there is about the degree to which different kinds of training enhance the flow of blood or the dilation of the arteries. In other words, we generally apparently want to reduce reactive hyperemia.

Now while i've seen claims that moderate rep schemes are "are optimal to build muscle mass " because in part they "Enhances cellular hydration — greater muscle pump (called "reactive hyperemia") drives plasma and water to muscle which stimulates protein synthesis and inhibits proteolysis (protein breakdown)." i can't find any sources that explain that plasma and water driven to a muscle stimulates protein synthesis. We do know is that protein stimulates muscle synthesis. And we know that insulin stimulates protein synthesis and glucose stimulates protein synthesis. So maybe if there's all that stuff in plasma, yes we have protein synthesis stimulation. But that seems to happen whether we have high or low rep training. But again, is more more?

An Idea: the Pump Works Like Occlusion?

Mr. Anderson above proposes that the pump mainly effects slow twitch oxidative fibers because of capilarization (no strength; just mass). Dr. Lowery suggests that not being able to get a pump is a sign of fatigue - this i think is important. BUT if we look at occlusion training (which reactive hyperemia seems to be a type), then the pump should also be affecting both fast and slow twitch fibers' myofibral growth. Occlulusion, it seems, may indeed get fast twitch fibers involved more directly than without occlusion - that's a theory. Since we also see in low load occlusion training effects on strength: it goes up. SO is this kind of self-occlusion with self-selected low resistance weights to induce the effect having the same effect as a cuff? Could be - as per this review.

So, what about that pump?

Proposal 1: more is more: As far as i can tell, the suggestions are that it's supposed to help circulate good stuff in by vasodilateion, and then get the stale stuff out. Now for me - based on what i know - this seems the weakest case since we're not talking about steady blood flow in and out with the pump, but "reactive hyperemia" which means that blood is pumped in, and it can't get out again for a good half hour. There's no "flushing" if that's the case is there? Dave Barr talks about the "anabolic pump" - but again, i can't find this in the literature.

Proposal 2: bulking up with fluid. The other proposal that anderson suggests - and i'm not sure where he gets it from, but seems to make sense, is that pushing a lot of blood into the veins - especially of slow twitch fibers - is going to cause the fibers that hold the blood to adapt - get thicker, more and denser capillaries (the little gates that open for blood to flow in but not back out). SO that's just bulking up - what most folks talk about as sarcoplasmic type hypertrophy - but this seems even more particular as it's strictly related to blood volume taking up more room.

Proposal 3: occlusion causing real muscle fiber change - or not. What makes more sense to me is a combo of this adaptation of capillaries AND actual fiber change potentially caused by self-occlusion. BUT folks like Chad Waterbury, respected strength coach, are very skeptical of the pump and any correlation to muscle gain.

No, look, lots of things give you a pump but don't make your muscles bigger. One of the best exercises I know for making your calves bigger is the jump squat, which doesn't cause a pump. But if you do a set of 50 calf raises, you'll get one hell of a pump, but it won't make your calves bigger.SO perhaps 50 calf raises aren't causing occlusion but then how could they cause a pump? I don't understand. Perhaps those calf raises do add muscle fiber but not mass? perhaps calves like abs are different? dunno. Interesting though.

Maybe, Maybe Not, It depends

As said, there's a lot that remains unknown about the whys and hows of hypertrophy. The role of the pump seems to be just as really clearly ambiguous as to whether or not it aids hypertrophy or not.

I like the correlation Lowery seems to make implicitly between achieving the pump and fatigue. That seems useful.

For myself, right now, it's fun to play with a pump well after i've completed the hard work of the strength workouts i'm doing. Whether it's doing anything functional or not, i dunno, but since there seems *some* sense to it, i'm willing to give it a bit of a go - for now.

And so... The above is not meant as an exhaustive overview of all things to do with the pump - it's just what i could find by a couple day's digging. IF there are studies that you know of that support or study the pump with respect to muscle hypertrophy, please add a comment. Will be keen to hear.

I wonder too if a study that took the same kind of athletes and one did a regular routine and the other finished with pump sets and the other didn't if that would be conclusive or that one would just say - well they other group did a bit more volume. I suppose one could vary the loads or reps. But it would be interesting to see some kind of work.

Also, i do know that just because it hasn't been researched doesn't mean there's not an effect, but as per that first "explanation" of why the pump works - supposedly - for hypertrophy - if one is going to provide physiological rationales for an effect, please just point to the mechanisms that have been shown to result in these effects - it has to be sourced somewhere. And if not, well, the best we can say is that, in some cases, there seems to be a strong correlation between pumping and hypertrophy - either sarcoplasmic or myofibral - what that mechanism is - pretty much unknown at the moment.

Again - this is just the best i can do right now to make sense of this concept. If you have more information/sources, please share.

Thanks

Related Posts:

- a gal deliberately trying to gain mass - eating for hypertrophy

- some recent work on occlusion training.

- general fitness practice b2d index

Citations:

Wernbom M, Augustsson J, & Raastad T (2008). Ischemic strength training: a low-load alternative to heavy resistance exercise? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 18 (4), 401-16 PMID: 18466185

Loenneke, J., & Pujol, T. (2009). The Use of Occlusion Training to Produce Muscle Hypertrophy Strength and Conditioning Journal, 31 (3), 77-84 DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181a5a352 Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Labels:

hyperemia,

hypertrophy,

integrating strength and cardio,

occlusion,

pump

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Does Cardio Interfere with Strength Training? How 'bout "no."

Follow @mcphoo

Tweet

A question that strength trainees ask at some point:

doesn't endurance (cardio) training interfere with strength training?

Great Question: Initially, starting in 1980 with Hickson, continuing through the 90's, as described in this super review by Andrew Burne, the answer was pretty much "yes."

Even more recent literature still seems to show that there is some interference effect, depending on volume/intensity of the types of training. More recently (2006) there has been a super article that says, ok, based on the findings that more consistently than not show an impact on explosive resistance training, let's consider what the molecular mechanisms are that may be involved to better tune training.

Even more recent literature still seems to show that there is some interference effect, depending on volume/intensity of the types of training. More recently (2006) there has been a super article that says, ok, based on the findings that more consistently than not show an impact on explosive resistance training, let's consider what the molecular mechanisms are that may be involved to better tune training.

There's a couple new studies, however, lead by Davis [1][2] that revisits this issue of assumed "interference." These studies are interesting on their own, but are particularly useful for reviewing the key ideas around when and how interference happens, if it happens, and why keeping that VO2max KB work in with the strength program is a Good Thing - though there's some other mixes that may have awesome results, too.

Davis is the researcher who in Jan 2008 showed that the effect on delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) can be mitigated by doing some cardio between sets (consider accelerated fast and loose) rather than just resting. He and his group seem to be applying similar protocols to strength training. That is, in the first Davis study, he had a group do serial concurrent exercise protocols (CE = strength and endurance) and what he defines as "integrated." Serial means that the group did their resistance training, then they did their aerobic stuff. The participants rested between sets of their lifts. Pretty standard prescription.

In the "integrated" version, participants did their aerobic work *during* their lifts, effectively between sets. Their heart rates were significantly higher across the complete period of their resistance trainng than their serial colleagues. This is not standard. How many times have you heard "leave your cardio till after your workout; you'll tire yourself out and won't be able to lift"

Here's the kicker: the results. First, the cool thing is we're talking well conditioned participants, not newbies (what i don't know is if they're new to resistance though), but second, the results will surprise you: the mean lower body strength of the serial group went up 17.2%. Not bad at all. The mean lower body strength of the integrated group, however, went up 23.3%. Intriguingly, gains in UPPER body strength were higher in the Serial group than the integrated. As for Endurance, both groups made big improvements; the integrated made more. As for body composition, not surprisingly perhaps, the integrated group was significantly better: 3.3% for integrated, vs 1.8% for serial.

The main take away, according to the authors, is that when compared to single mode training for strength, the concurrent exercise, both serial and integrated, made as good or better gains than single mode. So take that, interference ideas. Also, that by going "integrated" the gains across every marker (but upper body strength), were better in integrated practice.

A cool thing also shown is that there seems to be considerable benefit to strength by adding a Range of Motion cool down, rather than just strength work alone (if you don't have ROM work, consider some zhealth (overview of Z)).

The overview of interference by the authors:

Ok, i'll go along with the study showed that there were benefits of adding vigorous cardio (and ROM cool down) to strength. Great. It's also pretty clear that keeping your heart rate up (not resting between sets) is also a benefit to strength. This approach well supports and advances what Pavel's written about not sitting down between sets but keeping your heart up (see Enter The Kettlebell (review) as an example with its discussion of what to do between sets), though the rationale there was not particularly because it *improved* strength gains or reduced DOMS (as far as i recall, anyway).

What i don't quite see tested, and so not supported in the article is the critical issue of frequency. The authors claim that their work is "consistent" with other research on frequency. Which? the work that has shown that negative impacts with more days a week vs fewer days a week? or work that showed even low doses were troubling? The authors picked a nice middle-of-the-road protocol of 3 days a week for training and ONLY three days a week and got nice results.

We do know, that for whatever the myriad of factors, total density of training is a factor in any training plan, balancing recovery and effort, as Kenneth Jay keeps telling me, more an art than a strict science. It's not hard to believe, therefore, that tagging on additional effort to an already loaded program, could have a negative impact, whether resistance or cardio.

So why might the "integrated" approach be a goodie? Davis et al don't know. They have a really neat hypothesis, though, related to their earlier work on "cardioaccleration" and DOMS (remember, they found doing cardio between sets reduced DOMS).

When the DOMS article first came out, colleagues said they wouldn't want to sacrifice performance just to reduce DOMS - in other words the cardio during resistance would take away from the effort they could put in - they hypothesized. This latest study shows the reverse seems to be the case.

What does this CE result mean for our training?

So for folks who have been mixing up or integrating strength and intense cardio already (see the end of the Cardio/VO2Max article for examples of such protocols), this research just seems to add more support for the value of the approach for strength. What this result means for the rest of us? Well balanced CE programs are better for strength than strength training alone. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

doesn't endurance (cardio) training interfere with strength training?

Great Question: Initially, starting in 1980 with Hickson, continuing through the 90's, as described in this super review by Andrew Burne, the answer was pretty much "yes."

Even more recent literature still seems to show that there is some interference effect, depending on volume/intensity of the types of training. More recently (2006) there has been a super article that says, ok, based on the findings that more consistently than not show an impact on explosive resistance training, let's consider what the molecular mechanisms are that may be involved to better tune training.

Even more recent literature still seems to show that there is some interference effect, depending on volume/intensity of the types of training. More recently (2006) there has been a super article that says, ok, based on the findings that more consistently than not show an impact on explosive resistance training, let's consider what the molecular mechanisms are that may be involved to better tune training.There's a couple new studies, however, lead by Davis [1][2] that revisits this issue of assumed "interference." These studies are interesting on their own, but are particularly useful for reviewing the key ideas around when and how interference happens, if it happens, and why keeping that VO2max KB work in with the strength program is a Good Thing - though there's some other mixes that may have awesome results, too.

Davis is the researcher who in Jan 2008 showed that the effect on delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) can be mitigated by doing some cardio between sets (consider accelerated fast and loose) rather than just resting. He and his group seem to be applying similar protocols to strength training. That is, in the first Davis study, he had a group do serial concurrent exercise protocols (CE = strength and endurance) and what he defines as "integrated." Serial means that the group did their resistance training, then they did their aerobic stuff. The participants rested between sets of their lifts. Pretty standard prescription.

In the "integrated" version, participants did their aerobic work *during* their lifts, effectively between sets. Their heart rates were significantly higher across the complete period of their resistance trainng than their serial colleagues. This is not standard. How many times have you heard "leave your cardio till after your workout; you'll tire yourself out and won't be able to lift"

Here's the kicker: the results. First, the cool thing is we're talking well conditioned participants, not newbies (what i don't know is if they're new to resistance though), but second, the results will surprise you: the mean lower body strength of the serial group went up 17.2%. Not bad at all. The mean lower body strength of the integrated group, however, went up 23.3%. Intriguingly, gains in UPPER body strength were higher in the Serial group than the integrated. As for Endurance, both groups made big improvements; the integrated made more. As for body composition, not surprisingly perhaps, the integrated group was significantly better: 3.3% for integrated, vs 1.8% for serial.

The main take away, according to the authors, is that when compared to single mode training for strength, the concurrent exercise, both serial and integrated, made as good or better gains than single mode. So take that, interference ideas. Also, that by going "integrated" the gains across every marker (but upper body strength), were better in integrated practice.

A cool thing also shown is that there seems to be considerable benefit to strength by adding a Range of Motion cool down, rather than just strength work alone (if you don't have ROM work, consider some zhealth (overview of Z)).

The overview of interference by the authors:

- Many studies have postulated that training frequency is a variable as to whether or not interference occurs. There's nothing conclusive: "Evidence for the training frequency hypothesis is therefore suggestive but equivocal."

- Poor (untrained) physical condition of participants in studies has also been suggested as a factor for interference (or not) "Most studies cited here that report interference from CE used untrained or sedentary subjects, whereas most studies cited here that report absence of interference or synergy used well-trained subjects. Studies reporting absence of interference or synergy in medium- to high-frequency concurrent training protocols invariably used well-conditioned subjects" Most of these studies looked at effects on endurance athletes, it seems, not the other way around, and that's where the money is for most strength athletes like hard style kettlebellers.

- The usual hypothesis that timing of aerobic vs resistance work is a key factor, eg aerobics before, after or during resistance, isn't well established either. "The few studies that have evaluated exercise timing and sequence during concurrent training therefore suggest a possible effect, but its nature and prerequisites are unclear."

Ok, i'll go along with the study showed that there were benefits of adding vigorous cardio (and ROM cool down) to strength. Great. It's also pretty clear that keeping your heart rate up (not resting between sets) is also a benefit to strength. This approach well supports and advances what Pavel's written about not sitting down between sets but keeping your heart up (see Enter The Kettlebell (review) as an example with its discussion of what to do between sets), though the rationale there was not particularly because it *improved* strength gains or reduced DOMS (as far as i recall, anyway).

What i don't quite see tested, and so not supported in the article is the critical issue of frequency. The authors claim that their work is "consistent" with other research on frequency. Which? the work that has shown that negative impacts with more days a week vs fewer days a week? or work that showed even low doses were troubling? The authors picked a nice middle-of-the-road protocol of 3 days a week for training and ONLY three days a week and got nice results.

We do know, that for whatever the myriad of factors, total density of training is a factor in any training plan, balancing recovery and effort, as Kenneth Jay keeps telling me, more an art than a strict science. It's not hard to believe, therefore, that tagging on additional effort to an already loaded program, could have a negative impact, whether resistance or cardio.

So why might the "integrated" approach be a goodie? Davis et al don't know. They have a really neat hypothesis, though, related to their earlier work on "cardioaccleration" and DOMS (remember, they found doing cardio between sets reduced DOMS).

[T]he time course of DOMS reduction and elimination in both men and women trained in the integrated CE protocol is similar to the known time course of skeletal muscle angiogenesis, which may increase muscle perfusion during resistance exercise in the integrated CE group. The same mechanism could account for the apparent synergy of strength and endurance training in the integrated CE group. DOMS signifies contraction-induced muscle damage and consequent reduced capacity to generate muscular power for up to 72 hours (60), implying reduced responsiveness to strength training even in low-frequency (2 days per week) training protocols, whereas enhanced muscle perfusion increases muscle performance by up to 20% (44). The elimination of DOMS and consequent faster muscle recovery combined with enhanced muscle perfusion in the integrated CE protocol could therefore increase training adaptations compared with the serial CE protocol, as found in the present study, perhaps through the mechanism of enhanced postactivation potentiation of muscle responses to resistance exercises (11,12).In other words, their integrated approach is reducing DOMS which means faster recovery, which means accelerated growth/performance.

When the DOMS article first came out, colleagues said they wouldn't want to sacrifice performance just to reduce DOMS - in other words the cardio during resistance would take away from the effort they could put in - they hypothesized. This latest study shows the reverse seems to be the case.

What does this CE result mean for our training?

Enhanced training adaptations from integrated CE, combined with the potentially related elimination of DOMS (15) and consequent faster muscle recovery (21), therefore have the potential to improve training and clinical outcomes in exercise programs at all levels.It's worth looking at the article for exactly what intensity is being described in the CE protocol. Saying that, one of the big takeaways from the study is that, if the frequency is right (don't overdo your training. duh), and if you're already well conditioned, intense cardio + resistance are better for strength than strength work alone. If you want to take these benefits further, and enhance recovery, there's an opportunity to "integrate" resistance and "vigorous" / intense cardio.

So for folks who have been mixing up or integrating strength and intense cardio already (see the end of the Cardio/VO2Max article for examples of such protocols), this research just seems to add more support for the value of the approach for strength. What this result means for the rest of us? Well balanced CE programs are better for strength than strength training alone. Tweet Follow @begin2dig

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

COACHING with dr. m.c.

COACHING with dr. m.c.